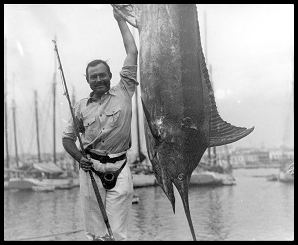

De Amerikaanse schrijver Ernest Hemingway werd geboren op 21 juli 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois. Hij won met het boek The old man and the sea in 1953 de prestigieuze Pulitzer Prize en in 1954 de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur. Zijn laatste levensjaren, waarin hij aan zware depressies leed, bracht hij hoofdzakelijk op Cuba door. Op 2 juli1961 benam hij zich met twee schoten uit zijn favoriete geweer het leven. Hij was niet de enige zijn familie die zelfmoord pleegde. Zijn vader, broer en zuster en zijn kleindochter kwamen op dezelfde manier aan hun eind.

Uit: The old man and the sea

“He hasn’t much faith.”

“No,” the old man said. “But we have. Haven’t we?”

“Yes,” the boy said. “Can I offer you a beer on the Terrace and then we’ll take the stuff home.”

“Why not?” the old man said. “Between fishermen.”

They

sat on the Terrace and many of the fishermen made fun of the old man

and he was not angry. Others, of the older fishermen, looked at him and

were sad. But they did not show it and they spoke politely about the

current and the depths they had drifted their lines at and the steady

good weather and of what they had seen. The successful fishermen of that

day were already in and had butchered their marlin out and carried them

laid full length across two planks, with two men staggering at the end

of each plank, to the fish house where they waited for the ice truck to

carry them to the market in Havana. Those who had caught sharks had

taken them to the shark factory on the other side of the cove where they

were hoisted on a block and tackle, their livers removed, their fins

cut off and their hides skinned out and their flesh cut into strips for

salting.

When

the wind was in the east a smell came across the harbour from the shark

factory; but today there was only the faint edge of the odour because

the wind had backed into the north and then dropped off and it was

pleasant and sunny on the Terrace.

“Santiago,” the boy said.

“Yes,” the old man said. He was holding his glass and thinking of many years ago.

“Can I go out to get sardines for you for tomorrow?”

“No. Go and play baseball. I can still row and Rogelio will throw the net.”

“I would like to go. If I cannot fish with you. I would like to serve in some way.”

“You bought me a beer,” the old man said. “You are already a man.”

“How old was I when you first took me in a boat?”

“Five and you nearly were killed when I brought

the fish in too green and he nearly tore the boat to pieces. Can you remember?”

“I

can remember the tail slapping and banging and the thwart breaking and

the noise of the clubbing. I can remember you throwing me into the bow

where the wet coiled lines were and feeling the whole boat shiver and

the noise of you clubbing him like chopping a tree down and the sweet

blood smell all over me.”

“Can you really remember that or did I just tell it to you?”

“I remember everything from when we first went together.”

The old man looked at him with his sun-burned, confident loving eyes.

“If

you were my boy I’d take you out and gamble,” he said. “But you are

your father’s and your mother’s and you are in a lucky boat.”

“May I get the sardines? I know where I can get four baits too.”

“I have mine left from today. I put them in salt in the box.”