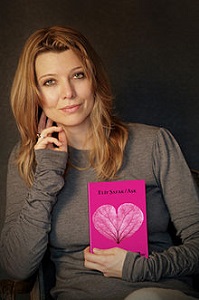

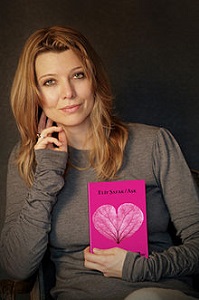

De Turkse schrijfster Elif Shafak (eigenlijk Elif Şafak) werd geboren in Straatsburg op 25 oktober 1971 en bleef na de scheiding van haar ouders bij haar moeder. Ze bracht haar tienerjaren door in Madrid en Amman (Jordanië), en keerde vervolgens terug naar Turkije. Ze studeerde Internationale Relaties aan de Technische Universiteit Midden-Oosten in Ankara. Ze heeft een diploma in Gender- en Vrouwenstudies en schreef een thesis getiteld The Deconstruction of Femininity Along the Cyclical Understanding of Heterodox Dervishes in Islam. Ze behaalde een doctoraat aan het departement Politieke Wetenschappen van dezelfde universiteit, met een thesis getiteld An Analysis of Turkish Modernity Through Discourses of Masculinities. Shafak werkte een jaar als onderzoeker aan Mount Holyoke Women’s College in South Hadley, Massachusetts in de Verenigde Staten. Daar schreef ze haar eerste roman in het Engels. De Nederlandse vertaling van het boek, “De heilige van de beginnende waanzin” (The Saint of Incipient Insanities), werd uitgegeven door De Geus.

Şafak was gastprofessor aan de University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan en aan het Near Eastern Studies Department van de University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. Daarna keerde ze terug naar Istanbul, een stad die ze een bron van liefde en inspiratie noemt. Ze verdeelt haar tijd tussen de Verenigde Staten en Istanbul. Şafak maakte haar literair debuut met het verhaal Kem Gözlere Anadolu, gepubliceerd in 1994. Haar eerste roman, Pinhan (“De Soefi”) kreeg de “Mevlana Prize” in 1998, die wordt toegekend aan het beste mystiek-literair werk in Turkije. Haar tweede roman, “Şehrin Aynaları” (“Spiegels van de stad”), verenigt joodse en islamitische mystiek tegen de achtergrond van de mediterrane 17de eeuw. Haar derde roman”Mahrem” (“De blik”) leverde haar de “Union of Turkish Writers’ Prize” op in 2000. “Bit Palas” (Het luizenpaleis) was een bestseller in Turkije. Shafak gebruikt de narratieve structuur van een verhaal van Duizend-en-één-nacht om een verhaal in het verhaal te vertellen. Op dit boek volgde “Med-Cezir”, een non-fictiewerk over gender, seksualiteit, mentale getto’s en literatuur. Ze schreef het voorwoord van “Türkçe Sevmek”, de vertaling van de bloemlezing van emigrantenliteratuur “Tales from the Expat Harem: Foreign Women in Modern Turkey”, over vrouw-zijn, nationale identiteit en het gevoel nergens bij te horen.

Şafaks boek “De Bastaard van Istanbul” leidde tot haar vervolging in Turkije op grond van “belediging van de Turksheid” onder Artikel 31 van de Turkse Strafwet.De vervolging was het gevolg van een uitspraak van één van de personages, die de moorden op Armeniërs tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog als genocide bestempelde. Shafak werd vrijgesproken.

Uit: The Bastard of Istanbul

„Whatever falls from the sky above, thou shall not curse it. That includes the rain.

No matter what might pour down, no matter how heavy the cloudburst or how icy the sleet, you should never ever utter profanities against whatever the heavens might have in store for us. Everybody knows this. And that includes Zeliha.

Yet, there she was on this first Friday of July, walking on a sidewalk that flowed next to hopelessly clogged traffic; rushing to an appointment she was now late for, swearing like a trooper, hissing one profanity after another at the broken pavement stones, at her high heels, at the man stalking her, at each and every driver who honked frantically when it was an urban fact that clamor had no effect on unclogging traffic, at the whole Ottoman dynasty for once upon a time conquering the city of Constantinople, and then sticking by its mistake, and yes, at the rain . . . this damn summer rain.

Rain is an agony here. In other parts of the world, a downpour will in all likelihood come as a boon for nearly everyone and everything—good for the crops, good for the fauna and the flora, and with an extra splash of romanticism, good for lovers. Not so in Istanbul though. Rain, for us, isn’t necessarily about getting wet. It’s not about getting dirty even. If anything, it’s about getting angry. It’s mud and chaos and rage, as if we didn’t have enough of each already. And struggle. It’s always about struggle. Like kittens thrown into a bucketful of water, all ten million of us put up a futile fight against the drops. It can’t be said that we are completely alone in this scuffle, for the streets too are in on it, with their antediluvian names stenciled on tin placards, and the tombstones of so many saints scattered in all directions, the piles of garbage that wait on almost every corner, the hideously huge construction pits soon to be turned into glitzy, modern buildings, and the seagulls. . . . It angers us all when the sky opens and spits on our heads.

But then, as the final drops reach the ground and many more perch unsteadily on the now dustless leaves, at that unprotected moment, when you are not quite sure that it has finally ceased raining, and neither is the rain itself, in that very interstice, everything becomes serene. For one long minute, the sky seems to apologize for the mess she has left us in. And we, with driblets still in our hair, slush in our cuffs, and dreariness in our gaze, stare back at the sky, now a lighter shade of cerulean and clearer than ever. We look up and can’t help smiling back. We forgive her; we always do.”

Elif Shafak (Straatsburg, 25 oktober 1971)