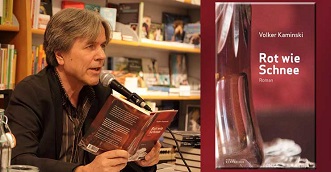

De Duitse schrijver Volker Kaminski werd op 14 juli 1958 in Karlsruhe geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Volker Kaminski op dit blog.

Uit: Rot wie Schnee

„Tom war sich sicher, dass der Junge nach ihm rief. Er glaubte seine helle Stimme zu hören, während er den Flur zwischen Küche und Atelier durchquerte. Er knips te das Neonlicht an und betrat das Atelier. Mach dich nicht verrückt, dachte er, es ist doch nur ein Bild. Die noch unfertige Leinwand, die an der Schmalseite des Raums lehnte, zeigte einen etwa siebzehnjährigen Jungen, der mit den Füßen im Schnee versank und sein bleiches Gesicht dem Betrachter zuwandte. Er hatte den Mund weit geöffnet und die Augen aufgerissen. In einer stark ausholenden Körperdrehung streckte er den rechten Arm nach hinten und deutete auf eine Stelle im Schnee, an der ein umgestürzter Wagen lag. Bettdecken, Körbe, große Kisten, verblichene Reisekoffer lagen im Schnee verstreut. Das Gestänge eines Vogelkäfigs ragte heraus, ein Fahrradlenker, eine alte Standuhr. Weiter hinten, halb verschüttet, aber gut sichtbar, lag eine junge Frau, die ihren gewölbten Bauch schützend mit den Armen bedeckte. Das Bild war 250 mal 180 Zentimeter groß, Toms bevor zugtes Standardmaß. Er hatte beschlossen, die Pferde weg zu lassen. Pferde würden das Elend zu sehr betonen, es wären Mitleid erregende Kreaturen, die aus offenen Wunden bluteten. Natürlich hätte er die Pferde an den Horizont stellen können, sie hätten still und ergeben dagestanden und damit angedeutet, um was für einen Wagen es sich handelte. Er musste jetzt wieder an die Pferde denken, obwohl er sich letzte Nacht gegen sie entschieden hatte. Es war ein Bild von der Flucht im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Der junge Mann im Vordergrund, der zerbrochene Wagen und der dichte Schnee gaben genügend Hinweise darauf. Tom nahm einen feinen Pinsel vom Tisch und machte sich wieder an die Arbeit. Keine Pferde, dachte er noch einmal. Der Schnee war das beherrschende, alles verschluckende Element. Er lag meterhoch, sodass man sich wildes, windgepeitschtes Schneetreiben vorstellen konnte. In der Szene selbst schneite es nicht. Es war keine einzige Schneeflocke zu sehen, nichts trat zwischen das Gesicht des Jungen und den Betrachter. So lebendig und aufgebracht sollte der Junge erscheinen, so plastisch und real, dass der Betrachter meinte, er steige zu ihm heraus. Dabei war Tom die Nähe zu dem Jungen beim Malen eher unangenehm; er fühlte sich beklommen, wenn er seinem Gesicht zu nahe kam. Als Vorlage diente ihm eine kleine SchwarzWeißFotografie, darauf war die Haltung, um die es ihm ging, nicht zu erkennen. Das Foto zeigte einen schmächtigen, freundlich lächelnden Schüler, keineswegs ein verzerrtes Gesicht. So angespannt und überdreht wie auf der Leinwand war er im Leben selten anzutreffen gewesen, aber Tom hatte sich dieser Ausdruck trotzdem tief eingeprägt. Er hatte manchmal von ihm als wild tanzendem Mann geträumt und sich für ihn im Traum geschämt. Im Zentrum seines Lebens hatte die Katastrophe gestanden, die mit dem Krieg über ihn hereingebrochen war. Und Tom hatte immer gewusst, dass er diese Katastrophe eines Tages auf die Leinwand bringen würde.“

De Japanse schrijfster Yukiko Motoya werd geboren op 14 juli 1979 in Hakusan, Ishikawa. Zie ook alle tags voor Yukiko Motoya op dit blog.

Uit: The Reason I Carry Biscuits to Offer to Young Boys (Vertaald door Asa Yoneda)

“Try these—they’re really delicious.”

I

was in the bus shelter opposite the train station, taking shelter from

the rain while I waited for my mom, when the guy with the umbrella

started talking to me. I hadn’t noticed him turn up but the old guy, who

was dressed in rags, gave me a friendly smile and offered me a little

packet of biscuits. “You look hungry,” he said. “Go ahead, they’re

really delicious.” Even though we were in the middle of a huge typhoon

and the ferocious wind was howling past my ears, I thought I caught a

whiff of the old guy’s sour smell.

“Aw,

biscuits!” I said, taking them like a good child. I was clutching the

biscuits inside my palm and nervously pretending to eat them when then

the guy pointed toward the junction where the wide station road met a

smaller road and, out of nowhere, said, “Don’t ever underestimate people

like them.” He was pointing at a man in a suit waiting for the lights

to turn, desperately holding his umbrella open in the storm.

I

didn’t react, but secretly I was pretty worried that he’d read my mind.

I’d been watching people just like suit man passing by, laughing at

them inside. Any time I saw typhoon coverage on TV, I just had to

wonder: What on earth were these people thinking? Walking along looking

totally focused on holding their barely open umbrellas in front of them

when their clothes, their hair and most likely even their socks were wet

through. I was like, Are you sure there isn’t something wrong with your

head? Don’t tell me you kowtow to umbrellas, at your age? But I’d never

mentioned these thoughts to anyone else.

“Just

watch,” said the old guy. “Soon he’ll be down to bare bones.” I didn’t

know what he meant, but his voice was strong like a sea captain’s, so I

looked to where his gnarly finger was pointing, at the man in a suit

holding on for dear life to the guardrail by the crossing. I’d nearly

been blown out onto the road there too, earlier, as I battled the rain

that blew horizontally into my face. Because it was a junction, the

strong winds bore straight at you.

“Three!

Two! One!” The old guy shouted, just as the man’s umbrella turned

inside out like a rice bowl and its fabric disappeared as though an

invisible man had ripped it off, instantly reducing the umbrella to just

its skeleton. I was speechless. The old guy’s timing had been perfect.

*

Associating

with people like him was a bad idea. I knew this, but his shabby

appearance and offensive smell didn’t bother me that much any more. He

handed me another packet of biscuits, and I pretended to nibble them

again, apologizing to him in my head for deceiving him. Oblivious to

that, the guy started telling a story about some boy from a tribe that

lived deep in a forest. It was about what the young kid did to win an

umbrella that a foreigner had brought to their village.

“They

beat each other with sticks,” said the guy. The wind was whipping his

long, tangled hair around, and it looked like the strands were trying to

feed on his face.”

De Amerikaanse schrijver Irving Stone werd geboren op 14 juli 1903 in San Francisco. Zie ook alle tags voor Irving Stone op dit blog.

Uit: Depths of Glory

“The opening of the official Salon on April 30, 1863, was attended by several thousand Parisians interested in art exhi-bitions. The jury gave a prize to the picture called The Pearl and the Wave, a young woman voluptuously extended on the bank receiving the embraces of the caressing waves. Corot and Millet were described by the judges as “foremost”. Gustave Courbet was infuriated because he had been described as “fad-ing and passing away”. Portrait of the Emperor was judged “the most important work of the exhibit”. Le Figaro’s critic was disappointed with the Salon. He wrote: “It is an honest and prudent French school. The general effect is sleepy”. The two weeks preceding the “Salon des Refuses” dragged unmercifully. When, a couple of days prior to the opening, the Emperor announced that he and his Empress would attend the showing of the unwanted artists, a shock wave went through Paris. Everyone who had been at the opening of the official Salon would have to attend this second Salon to see and be seen by their Majesties. It was expected that there would be an enormous crowd. “We’ll have a great success,” cried Claude Monet. Camille Pissarro responded, “You see, to be rejected is not the same as being ignored.” On the day of the opening he and his colleagues assembled in the passageway between Palais de l’Industrie and the adjoining building shortly before the opening hour. They found the exhibit as luxuriously mounted as that of the official Salon. Antique tapestries hung in the doorways. The benches were made comfortable with red velvet cushions. The skylights were covered with white cotton screens to cut the glare. There was a long series of display rooms. All like the official Salon.., except for the pictures. The brightness of their color, the mood, the authenticity of the figures and the presence of fresh air. The feeling of youth, of gaiety. Of innovation. In the two areas termed “the place of dishonor” were Edouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, two gentlemen fully clothed in vests, jackets and cravats, and two women entirely naked, sitting and gathering flowers, beside them the picnic basket and its luxurious contents overflowing into the foreground.“

Cover

De Italiaanse schrijfster Natalia Ginzburg werd geboren op 14 juli 1916 in Palermo. Zie ook alle tags voor Natalia Ginzburg op dit blog.

Uit: Al onze gisterens (Vertaald door Henny Vlot)

“Ze bleef altijd heel lang in de badkamer en dan kwam iedereen aan de deur kloppen, terwijl zij begon te roepen dat ze er ge-noeg van had in een huis te wonen waar niemand respect voor haar had; ze wilde meteen haar koffers pakken en naar haar zuster in Genua vertrekken. Twee of drie keer had ze haar koffers onder de kast vandaan gehaald en was ze begonnen haar schoenen in stoffen zakjes te stoppen. Je moest gewoon doen of er niets aan de hand was en dan haalde ze even later haar schoenen weer tevoorschijn. Overigens wist iedereen dat die zuster in Genua haar helemaal niet in huis wilde hebben.Juffrouw Maria kwam geheel gekleed, met haar hoed op, de badkamer uit en rende meteen de straat op met een schepje om mest te verzamelen voor de rozen, vliegensvlug, terwijl ze goed oplette dat er niemand aan kwam. Daarna ging ze inkopen doen met het boodschappennet, ze speelde het klaar om in een halfuur de hele stad door te rennen op haar vlugge voetjes in schoenen met een strik. Iedere morgen speurde ze de hele stad af naar koopjes, en kwam doodmoe thuis. Ze had altijd een slecht humeur als ze boodschappen had gedaan en viel uit tegen Concettina, die nog in haar ochtendjas rond-liep: ze zei dat ze nooit had gedacht dat ze nog eens met een boodschappennet door de stad zou moeten sjouwen, toen ze vroeger in het rijtuig naast grootmoeder zat, met haar knieën lekker warm onder de deken en de mensen die haar groet-ten. Concettina borstelde langzaam haar haar voor de spiegel, bracht daarna haar gezicht tot vlak bij het glas en bekeek een voor een haar sproeten, bekeek haar tanden en haar tandvlees, stak haar tong uit en bekeek die ook. Ze kamde haar haar strak naar achteren in een wrong in haar nek, met een warrige pony op haar voorhoofd; met die pony leek ze precies op een cocot-te, zei juffrouw Maria. Daarna deed ze de kast wijd open en dacht na over welke kleren ze zou aantrekken. Intussen luchtte juffrouw Maria de bedden en klopte de kleden, met een doek om haar hoofd en haar mouwen opgerold over haar oude, ta-nige armen. Maar ze dook weg bij het raam als ze de mevrouw van het huis aan de overkant het balkon op zag komen, want ze hield er niet van gezien te worden met haar hoofddoek om terwijl ze de kleden aan het kloppen was, en dan dacht ze er-aan terug dat ze in dit huis was gekomen als gezelschapsdame, en kijk nu eens wat ze moest doen.De overbuurvrouw had ook een pony, maar een door de kapper gekrulde, stijlvol verwarde pony, en juffrouw Maria zei dat ze jonger leek dan Concettina wanneer ze ’s morgens naar buiten kwam in haar lichtgekleurde, frisse peignoir, en toch wist iedereen zeker dat ze vijfenveertig was.Er waren dagen dat Concettina er niet in slaagde iets te vinden om aan te trekken.”

De Franse schrijver en letterkundige Jacques de Lacretelle werd geboren in Cormatin (Saône-et-Loire) op 14 juli 1888. Zie ook alle tags voor Jacques de Lacretelle op dit blog.

Uit: Silbermann

“Or,

Célestine, notre cuisinière, n’aimait pas cet homme « venu on ne sait

d’où », disait-elle, et lorsqu’elle avait eu affaire avec lui, on

l’entendait maugréer en revenant :

— C’est malheureux de voir ces beaux fruits touchés par ces mains-là.

Silbermann, ignorant ce petit mouvement instinctif, poursuivit :

—

Si les livres t’intéressent, tu viendras un jour chez moi, je te

montrerai ma bibliothèque et je te prêterai tout ce que tu voudras.

Je le remerciai et acceptai.

— Alors quand veux-tu venir ? dit-il aussitôt. Cet après-midi, es-tu libre ?

Je ne l’étais point. Il insista.

— Viens goûter jeudi prochain.

Il

y eut dans cet empressement quelque chose qui me déplut et me mit sur

la défensive. Je répondis que nous conviendrions du jour plus tard ; et

comme nous étions arrivés devant la maison de mes parents, je lui tendis

la main.

Silbermann la prit, la retint, et me regardant avec une expression de gratitude, me dit d’une voix infiniment douce :

— Je suis content, bien content, que nous nous soyons rencontrés… je ne pensais pas que nous pourrions être camarades.

— Et pourquoi ? demandai-je avec une sincère surprise.

—

Au lycée, je te voyais tout le temps avec Robin ; et comme lui, durant

un mois, cet été, a refusé de m’adresser la parole, je croyais que toi

aussi… Même en classe d’anglais où nous sommes voisins, je n’ai pas

osé…

Il

ne montrait plus guère d’assurance en disant ces mots. Sa voix était

basse et entrecoupée ; elle semblait monter de régions secrètes et

douloureuses. Sa main qui continuait d’étreindre la mienne comme s’il

eût voulu s’attacher à moi, trembla un peu.

Ce

ton et ce frémissement me bouleversèrent. J’entrevis chez cet être si

différent des autres une détresse intime, persistante, inguérissable,

analogue à celle d’un orphelin ou d’un infirme. Je balbutiai avec un

sourire, affectant de n’avoir pas compris :

— Mais c’est absurde… pour quelle raison supposais-tu…

—

Parce que je suis Juif, interrompit-il nettement et avec un accent si

particulier que je ne pus distinguer si l’aveu lui coûtait ou s’il en

était fier.”

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 14e juli ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag.