De Amerikaanse schrijver, scenarioschrijver en regisseur Arthur Laurents is geboren in New York op 14 Juli 1918.Zie ook alle tags voor Arthur Laurents op dit blog.

Uit: West Side Story

“SNOWBOY: What about the day we clobbered the Emeralds?

A-RAB: Which we couldn’t have done without Tony.

BABY JOHN: He saved my ever-lovin’ neck!

RIFF: Right! He’s always come through for us and he will now.

(sings)

When you’re a Jet,

You’re a Jet all the way

From your first cigarette

To your last dyin’ day.

When you’re a Jet,

If the spit hits the fan,

You got brothers around,

You’re a family man!

You’re never alone,

You’re never disconnected!

You’re home with your own:

When company’s expected,

You’re well protected!

Then you are set

With a capital J,

Which you’ll never forget

Till they cart you away.

When you’re a Jet,

You stay a Jet!

(spoken) I know Tony like I know me. I guarantee you can count him in.

ACTION: In, out, let’s get crackin’.

A-RAB: Where you gonna find Bernardo?

RIFF: At the dance tonight at the gym.

BIG DEAL: But the gym’s neutral territory.

RIFF: (innocently) I’m gonna make nice there! I’m only gonna challenge him.”

De Amerikaanse schrijver Owen Wister werd geboren op 14 juli 1860 in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Zie ook alle tags voor Owen Wister op dit blog.

Uit: The Virginian

„Annoyance blinded my eyes to all things save my grievance: I saw only a lost trunk. And I was muttering half-aloud, “What a forsaken hole this is!” when suddenly from outside on the platform came a slow voice:”Off to get married AGAIN? Oh, don’t!”

The voice was Southern and gentle and drawling; and a second voice came in immediate answer, cracked and querulous.”It ain’t again. Who says it’s again? Who told you, anyway?”

And the first voice responded caressingly:”Why, your Sunday clothes told me, Uncle Hughey. They are speakin’ mighty loud o’ nuptials.”

“You don’t worry me!” snapped Uncle Hughey, with shrill heat.

And the other gently continued, “Ain’t them gloves the same yu’ wore to your last weddin’?”

“You don’t worry me! You don’t worry me!” now screamed Uncle Hughey.

Already I had forgotten my trunk; care had left me; I was aware of the sunset, and had no desire but for more of this conversation. For it resembled none that I had heard in my life so far. I stepped to the door and looked out upon the station platform.

Lounging there at ease against the wall was a slim young giant, more beautiful than pictures. His broad, soft hat was pushed back; a loose-knotted, dull-scarlet handkerchief sagged from his throat; and one casual thumb was hooked in the cartridge-belt that slanted across his hips. He had plainly come many miles from somewhere across the vast horizon, as the dust upon him showed. His boots were white with it. His overalls were gray with it. The weather-beaten bloom of his face shone through it duskily, as the ripe peaches look upon their trees in a dry season. But no dinginess of travel or shabbiness of attire could tarnish the splendor that radiated from his youth and strength. The old man upon whose temper his remarks were doing such deadly work was combed and curried to a finish, a bridegroom swept and garnished; but alas for age! Had I been the bride, I should have taken the giant, dust and all. He had by no means done with the old man.

“Why, yu’ve hung weddin’ gyarments on every limb!” he now drawled, with admiration. “Who is the lucky lady this trip?”

In 1898

De Franse schrijfster van Belgische origine Béatrix Beck werd geboren in Villars-sur-Ollon op 14 juli 1914. Zie ook alle tags voor Béatrix Beck op dit blog.

Uit: L’enfant-chat

«Avec efforts elle grimpe sur le Divan à la Haute Muraille, en s’accrochant à la cretonne où les griffures se multiplient. Fait de l’alpinisme parmi les coussins, soudain a la nostalgie du sol mais ne peut tout de même pas faire un saut si vertigineux. En est réduite à se laisser tomber. Atterrit en catastrophe, accomplit à son rondelet corps défendant culbute et glissade. Du regard et de la voix exige d’être remontée à l’instant dans les montagnes, où elle se met à dormir de tout son coeur, avec application et sagesse.»

(…)

«La pelouse est une nappe de capucine (je confis et confie leurs graines au vinaigre) et des impatiences.»

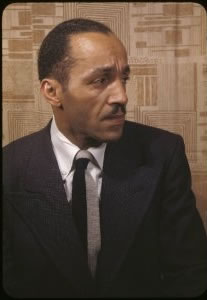

De Amerikaanse schrijver Willard Frances Motley werd geboren op 14 juli 1909 in Chicago. Zie ook alle tags voor Willard Motley op dit blog.

Uit: Pavement Portraits

„This is the corner. Here is where the women stand at night. This is where the evangelists preach God on Sundays. Here is where knife-play has written a moment’s strange drama; where sweethearts have met; where drunks have tilted bottles; where shoppers have bargained; where men have come looking — for something… This is the humpty-dumpty neighborhood. Maxwell and Newberry…

Here is where the daytime pavement never gets a rest from the shuffle of feet. Where the night-time street lamps lean drunkenly and are an easy target for the youngsters’ rocks. Where garbage cans are pressed full and running over. Where the weary buildings kneel to the street and the cats fight their fights under the tall, knock-kneed legs of the pushcarts. This is the down-to-earth world, the bread and beans world, the tenement-bleak world of poverty and hunger. The world of skipped meals; of skimp pocketbooks; of nonexistent security — shadowed by the miserable little houses that Jane Addams knew. Maxwell and Newberry…

This is the street of noises, of odors, of colors. This is a small hub around which a little world revolves. The spokes shoot off into all countries. This is Jerusalem. The journey to Africa is only one block; from Africa to Mexico one block; from Mexico to Italy two blocks; from Italy to Greece three blocks…

This is the pavement. These are the streets. Here are the people…“

Willard Motley (14 juli 1909 – 15 maart 1965)

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata:

De Amerikaanse schrijver Joshua Ferris werd op 8 november 1974 in Danville, Illinois geboren. Ferris debuteerde in 2006 met de roman Zo kwamen we aan het eind. Ferris studeerde Engels en filosofie aan de universiteit van Iowa, werkte een aantal jaren in de reclamewereld, en behaalde daarna een Master of Fine Arts aan de UC Irvine.

Uit: Zo kwamen we aan het eind (Vertaald door Peter Abelsen)

„We waren niet zo gedreven en overbetaald. Onze ochtenden hielden zelden een belofte in. Behalve voor de rokers, die konden uitzien naar kwart over tien. De meesten van ons vonden de meesten van ons wel aardig, sommigen hadden de pest aan één bepaald iemand, en een enkeling hield van alles en iedereen. Zij die van iedereen hielden, werden door alle anderen veracht. Niets kon ons blijer maken dan een gratis bagel in de ochtend. Het kwam veel te weinig voor dat die er waren.

Over het algemeen brachten we onze opdrachten kundig en op tijd tot een goed einde. Soms werd er geblunderd. Drukfouten, verhaspelde telefoonnummers. We zaten in de reclame en details waren belangrijk. Als in het gratis nummer van een klant het derde cijfer na het tweede streepje een acht werd terwijl het een zes moest zijn, en het nummer ging zo naar de drukker, en kwam zo in Time Magazine te staan, dan konden de lezers daarvan niet bellen-en-direct-bestellen. Het deed er niet toe dat ze hun bestelling ook op de website konden doen. Het geld voor die advertentie konden we dan op onze buik schrijven. Verveelt dit u al? Het verveelde ons elke dag. Onze verveling was permanent, het was een collectieve verveling, en die zou er altijd zijn omdat wij er altijd zouden zijn.“

De Nigeriaanse schrijfster Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie werd geboren op 15 september 1977 in Enugu. Haar romans zijn in meerdere talen vertaald, waaronder Duits, Spaans, Nederlands. Zij woont afwisselend in Nigeria en in de VS.

Uit: Purple Hibiscus

„Jaja did not move. Papa swayed from side to side. I stood at the door, watching them. The ceiling fan spun round and round, and the light bulbs attached to it clinked against one another. Then Mama came in, her rubber slippers making slap-slap sounds on the marble floor. She had changed from her sequined Sunday wrapper and the blouse with puffy sleeves.

Now she had a plain tie-dye wrapper tied loosely around her waist and that white T-shirt she wore every other day. It was a souvenir from a spiritual retreat she and Papa had attended; the words GOD IS LOVE crawled over her sagging breasts. She stared at the figurine pieces on the floor and then knelt and started to pick them up with her bare hands.

The silence was broken only by the whir of the ceiling fan as it sliced through the still air. Although our spacious dining room gave way to an even wider living room, I felt suffocated. The off-white walls with the framed photos of Grandfather were narrowing, bearing down on me. Even the glass dining table was moving toward me.

“Nne, ngwa. Go and change,” Mama said to me, startling me although her Igbo words were low and calming. In the same breath, without pausing, she said to Papa, “Your tea is getting cold,” and to Jaja, “Come and help me, biko.”

Papa sat down at the table and poured his tea from the china tea set with pink flowers on the edges. I waited for him to ask Jaja and me to take a sip, as he always did. A love sip, he called it, because you shared the little things you loved with the people you loved. Have a love sip, he would say, and Jaja would go first. Then I would hold the cup with both hands and raise it to my lips. One sip.“