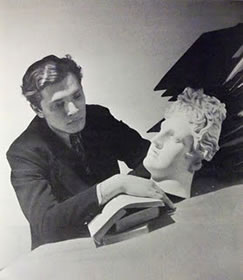

De Britse schrijver Louis de Bernières werd geboren in Londen op 8 december 1954. Zie ook alle tags voor Louis de Bernières op dit blog.

Uit: Birds Without Wings

„Yusuf the Tall strode up and down the room, waving his hands, protesting and expostulating, sometimes burying his face in his hands. Kaya had not seen him so anguished and begrieved since the death of his mother three years before. He had painted the tulip on the headstone with his own hands, and had taken bread and olives so that he could eat at the graveside, imagining his mother underneath the stones, but unable to picture her as anything but living and intact.

Yusuf had passed the stage of anger. The time had gone when these patrollings of the room had been accompanied by obscenities so fearful that Kaya and her children had had to flee the house with their hands over their ears, their heads ringing with his curses against his daughter and the Christian: “Orospu çocu¢gu! Orospu çocu¢gu! Piç!”

By now, however, Yusuf the Tall was in that state of grief which foreknew in its full import the horror of what was inescapably to come. His face glistened with anticipatory tears, and when he threw his head back and opened his mouth to groan, thick saliva strung itself across his teeth.

Overtaken, finally, by weariness, Kaya had given up pleading with him, partly because she herself could see no other way to deal with what had occurred. If it had been a Muslim, perhaps they could have married her to him, or perhaps they could have repeated what had been done with Tamara Hanim. Perhaps they could have kept her concealed in the house, unmarried for ever, and perhaps the child could have been given away. Perhaps they could have left it at the gates of a monastery. Perhaps they could have sent her away in disgrace, to fend for herself and suffer whatever indignities fate and divine malice should rain upon her head. It had not been a Muslim, however, it had been an infidel.

Yusuf was an implacable and undeviating adherent to his faith. Originally from Konya, he was not like the other Muslims of this mongrel town who seemed to be neither one thing nor the other, getting converted when they married, drinking wine with Christians either overtly or in secret, begging favours in their prayers from Mary Mother of Jesus, not asking what the white meat was when they shared a meal, and being buried with a silver cross wrapped in a scrap of the Koran enfolded in their hands, just because it was wise to back both camels in salvation’s race.“

Louis de Bernières (Londen, 8 december 1954)

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Mary Catherine Gordon werd geboren op 8 december 1949 in Far Rockaway, New York. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 december 2008 en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2009. en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2010.

Uit:The Love of My Youth

„“I hope it won’t be strange or awkward. I mean, what seemed strange to me, or would seem strange, is not to do it. Because in a way it is strange, isn’t it, really, the two of you in Rome at the same time, the both of you phoning me the same day?”

Irritation bubbles up in Miranda. Had Valerie always been so garrulous? So vague? Had she, Miranda, always found her so annoying — the qualifications, the emendations, laid down, thrown out like straw on a road to muffle the noise of passing carriages when there’d been a death in the house? Where did that come from? Some novel of the nineteenth century. The early twentieth. And now it is the twenty-first, the first decade nearly done for. There’s no point in thinking this way, focusing on Valerie’s habits of speech and diction. As if that were the point. The point is simply: she must decide whether or not to go.

It has been nearly forty years since she has seen him. Or to be exact — and it is one of the things she values in herself, her ability to be exact — thirty-six years and four months. She saw him last on June 23, 1971. The day had changed her.

Adam tries to remember if he had ever been genuinely fond of Valerie. What he can recall is that, of Miranda’s many friends, Valerie was the one who seemed most interested in him. The one who asked him questions and then listened to his answers, who assumed he had a life whose details might be worthy of her attention. 1966, ’67, ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71. A time when he spent his days trying to determine the perfect fingering, the ideal tempo, for a Beethoven sonata, a Bach partita. A way of spending time that Miranda’s friends considered almost criminally beside the point. The point was stopping the war. Stopping racism. Stopping poverty. Diminishing the injustice of the world.”

Mary Gordon (Far Rockaway, 8 december 1949)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Bill Bryson werd geboren in Des Moines (Iowa) op 8 december 1951. Zie ookmijn blog van 8 december 2007 en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2008 en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2009. en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2010.

Uit: A Walk In The Woods

“Stephen, you awake?” I whispered.

“Yup,” he replied in a weary but normal voice.

“What was that?”

“How the hell should I know.”

“It sounded big.”

“Everything sounds big in the woods.”

This was true. Once a skunk had come plodding through our camp and it had sounded like a stegosaurus. There was another heavy rustle and then the sound of lapping at the spring. It was having a drink, whatever it was.

I shuffled on my knees to the foot of the tent, cautiously unzipped the mesh and peered out, but it was pitch black. As quietly as I could, I brought in my backpack and with the light of a small flashlight searched through it for my knife. When I found it and opened the blade I was appalled at how wimpy it looked. It was a perfectly respectable appliance for, say, buttering pancakes, but patently inadequate for defending oneself against 400 pounds of ravenous fur.

Carefully, very carefully, I climbed from the tent and put on the flashlight, which cast a distressingly feeble beam. Something about fifteen or twenty feet away looked up at me. I couldn’t see anything at all of its shape or size–only two shining eyes. It went silent, whatever it was, and stared back at me.

“Stephen,” I whispered at his tent, “did you pack a knife?”

“No.”

“Have you get anything sharp at all?”

He thought for a moment. “Nail clippers.”

I made a despairing face. “Anything a little more vicious than that? Because, you see, there is definitely something out here.”

“It’s probably just a skunk.”

“Then it’s one big skunk. Its eyes are three feet off the ground.”

“A deer then.”

I nervously threw a stick at the animal, and it didn’t move, whatever it was. A deer would have bolted. This thing just blinked once and kept staring.

I reported this to Katz.

“Probably a buck. They’re not so timid. Try shouting at it.”

Bill Bryson (Des Moines, 8 december 1951)

De Amerikaanse dichter en schrijver Delmore Schwartz werd geboren op 8 december 1913 in New York. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 december 2008 en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2009. en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2010.

Faust In Old Age

“Poet and veteran of childhood, look!

See in me the obscene, for you have love,

For you have hatred, you, you must be judge,

Deliver judgement, Delmore Schwartz.

Well-known wishes have been to war,

The vicious mouth has chewed the vine.

The patient crab beneath the shirt

Has charmed such interests as Indies meant.

For I have walked within and seen each sea,

The fish that flies, the broken burning bird,

Born again, beginning again, my breast!

Purple with persons like a tragic play.

For I have flown the cloud and fallen down,

Plucked Venus, sneering at her moan.

I took the train that takes away remorse;

I cast down every king like Socrates.

I knocked each nut to find the meat;

A worm was there and not a mint.

Metaphysicians could have told me this,

But each learns for himself, as in the kiss.

Polonius I poked, not him

To whom aspires spire and hymn,

Who succors children and the very poor;

I pierced the pompous Premier, not Jesus Christ,

I picked Polonius and Moby Dick,

the ego bloomed into an octopus.

Now come I to the exhausted West at last;

I know my vanity, my nothingness,

now I float will-less in despair’s dead sea,

Every man my enemy.

Spontaneous, I have too much to say,

And what I say will no one not old see:

If we could love one another, it would be well.

But as it is, I am sorry for the whole world, myself

apart. My heart is full of memory and desire, and in

its last nervousness, there is pity for those I have

touched, but only hatred and contempt for myself.”

Delmore Schwartz (8 december 1913 – 11 juli 1966)

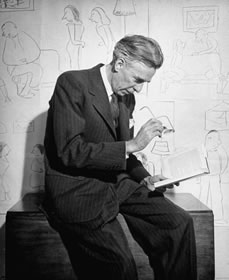

De Amerikaanse schrijver James Thurber werd geboren op 8 december 1894 in Columbus, Ohio. Zie ook alle tags voor James Thurber op dit blog.

Uit: The Last Clock

“Wuld wuzzle?” the ogre wanted to know. He hiccuped, and something went spong!

“That was an area man, but the wrong area,” the ogress explained. “I’ll get a general practitioner.” And she went away and came back with a general practitioner.

“This is a waste of time,” he said. “As a general practitioner, modern style, I treat only generals. This patient is not even a private. He sounds to me like a public place — a clock tower, perhaps, or a belfry..”

“What should I do?” asked the ogress. “Send for a tower man, or a belfry man?”

“I shall not venture an opinion,” said the general practitioner. “I am a specialist in generals, one of whom has just lost command of his army and of all his faculties, and doesn’t know what time it is. Good day.” And the general practitioner went away.

The ogre cracked a small clock, as if were a large walnut, and began eating it. “Wulsy wul?” the ogre asked.

The ogress, who could now talk clocktalk fluently, even oilily, but wouldn’t, left the room to look up specialists in an enormous volume entitled “Who’s Who in Areas.” She soon became lost in a list of titles: clockmaker, clocksmith, clockwright, clockmonger, clockician, clockometrist, clockologist, and a hundred others dealing with clockness, clockism, clockship, clockdom, clockation, clockition, and clockhood.

The ogress decided to to call on an old inspirationalist who had once advised her father not to worry about a giant he was worrying about. The inspirationalist had said to the ogress’s father, “Don’t pay any attention to it, and it will go away.” And the ogress’s father had paid no attention to it, and it had gone away, taking him with it, and this had pleased the ogress. The inspirationalist was now a very old man whose inspirationalism had become a jumble of mumble. “The final experience should not be mummum,” he mumbled.

The ogress said, “But what is mummum?”

“Mummum,” said the inspirationalist, “is what the final experience should not be.” And he mumbled to a couch, lay down upon it, and fell asleep.”

James Thurber (8 december 1894 – 2 november 1961)

De Amerikaanse dichter en schrijver William Hervey Allen werd geboren op 8 december 1889 in Pittsburgh. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 december 2008 en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2009. en ook mijn blog van 8 december 2010.

Beyond debate

Out from the wrought-iron gate

Miss Perdee drives in state;

Miss Perdee wears the thin smile

And the sleeves of 1888.

Miss Perdee’s face is stifled as a sonnet;

Upon her wire-tight hair a duck-shaped bonnet

Nests, nodding with a cachepeigne

Of violets on it.

East Bay, some tea and talk, them home by King.

The horses have an antiquated plod;

The team is old, but not too old to balk

If driven north of Broad.

Miss Perdee wears the sure air of a queen,

Which only queens and Perdees can achieve.

The Perdees had blue blood in Adam’s veins

When Adam had the rib he gave to Eve.

Back through the wrought-iron gate

Miss Perdee drives in state.

Miss Perdee lives down on the Battery!

Beyond debate.

Hervey Allen (8 december 1889 – 28 december 1949)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 8e december ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag.