De Britse schrijver Philip Ballantyne Kerr werd geboren in Edinburgh op 22 februari 1956. Kerr studeerde rechten en juridische filosofie aan de universiteit van Birmingham en werkte daarna in een reclamebureau. 1989, zijn eerste roman, “March Violets”, die speelt in de jaren 1930 in Berlijn, een mix van historische roman en thriller die internationale erkenning ontving en waaraan in Frankrijk de Prix du Roman d’Aventures en de Prix Mystère de la critique werd toegekend. Vanuit het debuut ontwikkelde zich de misdaadtrilogie “Berlin Noir” over de privédetective en voormalige hoofdinspecteur Bernhard Gunther. Verschillende bijfiguren zijn niet fictief, zoals Ernst Gennat (destijds politiecommissaris van Berlijn), Reinhard Heydrich, Bernhard Weiß (een Joods politicus), Arthur Nebe, Adolf Eichmann, Horst Carlos Fuldner (een nazi-agent in Argentinië) en Joseph Mengele. Zijn romans en thrillers schreef hij onder zijn eigen naam en zijn kinderboekenserie “Children of the Lamp” als P.B. Kerr.

Uit: The Other Side of Silence

„Yesterday I tried to kill myself.

It wasn’t that I wanted to die as much as the fact that I wanted the pain to stop. Elisabeth, my wife, left me a while ago and I’d been missing her a lot. That was one source of pain, and a pretty major one, I have to admit. Even after a war in which more than four million German soldiers died, German wives are hard to come by. But another serious pain in my life was the war itself of course, and what happened to me back then, and in the Soviet POW camps afterwards. Which perhaps made my decision to commit suicide odd considering how hard it was not to die in Russia; but staying alive was always more of a habit for me than an active choice. For years under the Nazis I stayed alive out of sheer bloody mindedness. So I asked myself, early one Spring morning, why not kill yourself? To a Goethe-loving Prussian like me the pure reason of a question like that was almost unassailable. Besides, it wasn’t as if life was so great anymore, although in truth I’m not sure it ever was. Tomorrow and the long, long empty year to come after that isn’t something of much interest to me, especially down here on the French Riviera. I was on my own, pushing sixty and working in a hotel job that I could do in my sleep, not that I got much of that these days. Most of the time I was miserable. I was living somewhere I didn’t belong and it felt like a cold corner in hell, so it wasn’t as if I believed anyone who enjoys a sunny day would miss the dark cloud that was my face.

There was all that for choosing to die, plus the arrival of a guest at the hotel. A guest I recognized and wished I hadn’t. But I’ll come to him in a moment. Before that I have to explain why I’m still here.

I went into the garage underneath my small apartment in Villefranche, closed the door, and waited in the car with the engine turning over. Carbon monoxide poisoning isn’t so bad. You just close your eyes and go to sleep. If the car hadn’t stalled or perhaps just run out of gas I wouldn’t be here now. I thought I might try it again another time, if things didn’t improve and if I bought a more reliable motor car. On the other hand, I could have returned to Berlin, like my poor wife, which might have achieved the same result. Even today it’s just as easy to get yourself killed there as it ever was and if I were to go back to the former German capital, I don’t think it would be very long before someone was kind enough to organize my sudden death. One side or the other has got it in for me, and with good reason. When I was living in Berlin and being a cop or an ex-cop, I managed to offend almost everyone, with the possible exception of the British.”

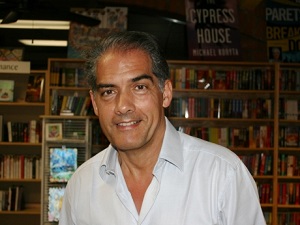

Philip Kerr (Edinburgh, 22 februari 1956)