De Zuidkoreaanse schrijver Yi Mun-yol werd geboren op 18 mei 1948 in Yongyang. Zie ook alle tags voor Yi Mun-yol op dit blog.

Uit: Our Twisted Hero (Vertaald door Kevin O’Rourke)

“As soon as my mother brought me into the room, the teacher in charge came over to greet us. He too fell far short of my expectations. If we couldn’t have a beautiful and kind female teacher, I thought at least we might have a soft-spoken, considerate, stylish male one. But the white rice-wine stain on the sleeve of his jacket told me he didn’t measure up. His hair was tousled; he had not combed it much less put oil on it. It was very doubtful if he had washed his face that morning, and his physical attitude left grave doubts about whether he was actually listening to Mother. Frankly, it was indescribably disappointing that such a man was to be my new teacher. Perhaps already I had a premonition of the evil that was to unfold over the course of the next year.

That evil showed itself days later when I was being introduced to the class.

“This is the new transfer student, Han Pyongt’ae. I hope you get on well.”

The teacher, having concluded this one line introduction, seated me in an empty chair in the back and went directly into classwork. When I thought of how considerate my Seoul teachers had been in invariably giving prolonged proud introductions to new students, almost to the point of embarrassment, I could not hold back my disappointment. He didn’t have to give me a big buildup, but he could at least have told the other children about some of the things I had to my credit. It would have helped me begin to relate to the others and them to me.

There were a couple of things the teacher could have mentioned. First of all, there was my school work. I may not have been first very often, but I was in the first five in my class in an outstanding Seoul school. I was quietly proud of this; it had played no small part in ensuring good results in my relations not only with teachers but also with the other children. I was also very good at painting.I was not good enough to sweep a national children’s art contest, but I did get the top award in a number of contests at the Seoul level. I presume my mother stressed my marks and artistic ability several times, but the teacher ignored them completely. In some circumstances, my father’s job, too, could havebeen a help. So what if he had suffered a setback in Seoul, even a bad one, bad enough to drive him from Seoul to here? He still ranked with the top few civil servants in this small town.”

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Markus Breidenich werd geboren in Düren op 18 mei 1972. Zie ook alle tags voor Markus Breidenich op dit blog.

Im Herbarium

Wir hatten Blätter, aufgehängt zum Trocknen,

über uns. Den letzten Mückenstich in Kupfer schon

gepresst. Von Blütenträumen falscher Zwanziger

berieselt, in Bücher uns vergraben. Alte

Würmer, in erotischen Motiven. Reich

der Carnivoren: Venusfliegenfallen, schön:

Auf hadernhaltigem Papier der Druck der abge-

schlossenen Kapitel, waren wir. In Blei gesetzte

Namen, Spiegelschrift, der Rosen.

Fliegen

Aufeinander so fliegen. Bestäubtest du nicht

die Bücher meiner Regale? Die Narben. Narben

im Innern der Zimmer. Wachsen. Jetzt warte.

Warte auf Blütenkelche und blaue Himmel.

Dann findest du Honig in gläsernen Spendern.

Und weißt. Du weißt von den Körnerbrötchen.

Streichzarten Butterblumen so viel. Dem

Aufstrich der Rosen im Fenstereck. Dann

siehst du den Blättern das Grünzeug an. Das

über den Tischen wächst. Bis über die Dielen

Schatten wirft. Durch Scheiben die Sonne auf

Quittengelee. Fällt ein Tropfen mir ein

von Johannisbeersaft. Von dir ist der Nektar in

wabenförmigen Eiswürfelbechern. Der Tau

aller frisch gepressten Gräser. In Seiten von

Alben. Erinnerungsstücken. Von uns. Und

von dir ist das Summen der Boxen am Morgen.

Das strahlende Spiel auf den Flügeln. Komm.

Lass noch einmal uns kreisen und über den

Krümeln eine Fliege uns machen. Zu zweit.

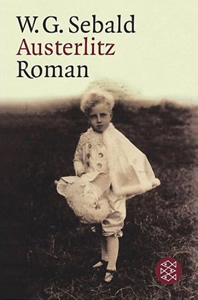

De Duitse schrijver W.G. Sebald werd geboren in Wertach (Allgäu) op 18 mei 1944. Zie ook alle tags voor W. G. Sebald op dit blog.

Uit: Austerlitz (Vertaald door Anthea Bell)

“It was several months after this meeting in Liege that I came upon Austerlitz, again entirely by chance, on the old Gallows Hill in Brussels, on the steps of the Palace of justice which, as he immediately told me, is the largest accumulation of stone blocks anywhere in Europe. The building of this singular architectural monstrosity, on which Austerlitz was planning to write a study at the time, began in the 1880s at the urging of the bourgeoisie of Brussels, over-hastily and before the details of the grandiose scheme submitted by a certain Joseph Poelaert had been properly worked out, as a result of which, said Austerlitz, this huge pile of over seven hundred thousand cubic meters contains corridors and stairways leading nowhere, and doorless rooms and halls where no one would ever set foot, empty spaces surrounded by walls and representing the innermost secret of all sanctioned authority.

Austerlitz went on to tell me that he himself, looking for a labyrinth used in the initiation ceremonies of the Freemasons, which he had heard was in either the basement or the attic story of the palace, had wandered for hours through this mountain range of stone, through forests of columns, past colossal statues, upstairs and downstairs, and no one ever asked him what he wanted.

During these wanderings, feeling tired or wishing to get his bearings from the sky, he had stopped at one of the windows set deep in the walls to look out over the leaden gray roofs of the palace, crammed together like pack ice, and down into ravines and shaft-like interior courtyards never penetrated by any ray of light.”

De Franse schrijver François Nourissier werd geboren op 18 mei 1927 in Parijs. Zie ook alle tags voor François Nourissier op dit blog.

Uit: Lettre à mon chien

« S’il est vrai qu’on a les chiens qu’on mérite, comme je suis fier de ta démence et de tes tendresses ! Dans cette vie de partout corsetée, colmatée, nourrie de labeurs et de décorations, tu es la fuite du cœur, la fissure par où s’insinuent les déraisons. Il y a trente ans je ne t’aurais pas méritée, justement, j’étais trop empêtré d’ordre et de calculs. Je croyais aux investissements. »

“Chaque matin à mon réveil, tu me rappelles – leçon sans prix – que la gravité est une grimace repoussante et que seules comptent les fêtes de la vie. Puissé-je m’en souvenir au jour de la grande peine de ton départ – si je suis là pour la souffrir.”

(…)

“Chaque matin à mon réveil, tu me rappelles – leçon sans prix – que la gravité est une grimace repoussante et que seules comptent les fêtes de la vie. Puissé-je m’en souvenir au jour de la grande peine de ton départ – si je suis là pour la souffrir.”

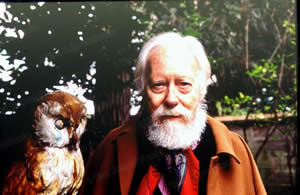

De IJslandse dichter en schrijver Gunnar Gunnarsson werd geboren op 18 mei 1889 in Fljótsdalur. Zie ook alle tags voor Gunnar Gunnarsson op dit blog.

Uit: Father And Son (Vertaald door Peter Foote)

“Among the few words that passed between them, however, was one sentence that came up again and again–when old Snjolfur was talking to his son. His words were:

The point is to pay your debts to everybody, not owe anybody anything, trust in Providence.

In fact, father and son together preferred to live on the edge of starvation rather than buy anything for which they could not pay on the spot. And they tacked together bits of old sacking and patched and patched them so as to cover their nakedness, unburdened by debt.

Most of their neighbours were in debt to some extent; some of them only repaid the factor at odd times, and they never repaid the whole amount. But as far as little Snjolfur knew, he and his father had never owed a penny to anyone. Before his time, his father had been on the factor’s books like everyone else, but that was not a thing he spoke much about and little Snjolfur knew nothing of those dealings.

It was essential for the two of them to see they had supplies to last them through the winter, when for many days gales or heavy seas made fishing impossible. The fish that had to last them through the winter was either dried or salted; what they felt they could spare was sold, so that there might be a little ready money in the house against the arrival of winter. There was rarely anything left, and sometimes the cupboard was bare before the end of the winter; whatever was eatable had been eaten by the tune spring came on, and most often father and son knew what it was like to go hungry”.

Hier met collega schrijver Halldór Laxness (rechts) in 1947

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 17e mei ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag.