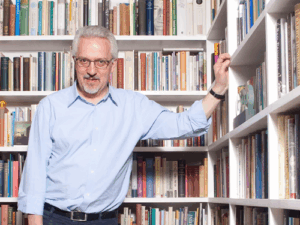

De Britse schrijver Alan Hollinghurst werd geboren op 26 mei 1954 in Stoud, Gloucestershire. Zie ook alle tags voor Alan Hollinghurst op dit blog.

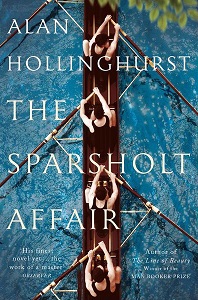

Uit: The Sparsholt Affair

“The evening when we first heard Sparsholt’s name seems the best place to start this little memoir. We were up in my rooms, talking about the Club. Peter Coyle, the painter, was there, and Charlie Farmonger, and Evert Dax. A sort of vote had taken place, and I had emerged as the secretary. I was the oldest by a year, and as I was exempt from service I did nothing but read. Evert said, “Oh, Freddie reads two books a day,” which may have been true; I protested that my rate was slower if the books were in Italian, or Russian. That was my role, and I played it with the supercilious aplomb of a student actor. The whole purpose of the Club was getting well-known writers to come and speak to us, and read aloud from their latest work; we offered them a decent dinner, in those days a risky promise, and after dinner a panelled room packed full of keen young readers—a provision we were rather more certain of. When the bombing began people wanted to know what the writers were thinking.

Now Charlie suggested Orwell, and one or two names we had failed to net last year did the rounds again. Might Stephen Spender come, or Rebecca West? Nancy Kent was already lined up, to talk to us about Spain. Evert in his impractical way mentioned Auden, who was in New York, and unlikely to return while the War was on. (“Good riddance too,” said Charlie.) It was Peter who said, surely knowing how Evert was hoping he wouldn’t, “Well, why don’t we get Dax to ask Victor?” The world knew Evert’s father as A. V. Dax, but we claimed this vicarious intimacy.

Evert had already slipped away towards the window, and stood there peering into the quad. There was always some tension between him and Peter, who liked to provoke and even embarrass his friends. “Oh, I’m not sure about that,” said Evert, over his shoulder. “Things are rather difficult at present.”

“Well, so they are for everyone,” said Charlie.

Evert politely agreed with this, though his parents remained in London, where a bomb had brought down the church at the end of their street a few nights before. He said, rather wildly, “I just worry that no one would turn up.”

“Oh, they’d turn up, all right,” said Charlie, with an odd smile.

Evert looked round, he appealed to me—“I mean, what do you make of it, the new one?”

Alan Hollinghurst (Stoud, 26 mei 1954)

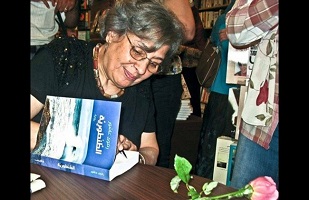

De Egyptische schrijfster en literatuurwetenschapster Radwa Ashour werd geboren op 26 mei 1946 in Caïro. Zie ook alle tags voor Radwa Ashour op dit blog.

Uit:Granada (Vertaald door William Granara)

“Abu Mansour was sitting on the proprietor’s bench in the bathhouse to the right of the front door. He mumbled a response to the two men’s greetings, then pointed to the closet where they kept the clean folded towels. Saad took three towels and followed his master up three steps that lead to the western wing, where he helped him take off his clothes and cover up his nakedness with a loincloth he wrapped around his waist. He carefully folded his master’s clothes and placed them in a large silk garment bag. Then he took off his own clothes except for his drawers and put them into an old sack. He handed both bundles to Abu Mansour, who kept his head bowed down and said nothing.

Before entering the bath proper, the master went into the toilet while Saad sat waiting on one of the benches. There were only three other men in the central foyer. Two of them sat on a bench opposite Saad, while the third, a tall, lean man, paced back and forth, crossing the large foyer from the front door to the back door.

Saad was wondering what was wrong with Abu Mansour. He wanted to know if he was sick but didn’t dare ask. It wasn’t like him to sit at the entrance to the bathhouse like all the other bathhouse owners. He would rather have one of his employees sit there and take the customers’ belongings while he would skitter about, shuffling hurriedly from one room to another, bringing soap to a client or a basin to another, or perhaps a loincloth or a towel to whomever asked for one. He would stop to tell an amusing story or crack a joke that would make everyone roar with laughter. He was a portly man in his fifties, or maybe even his forties. He had a ruddy complexion, finely chiseled features, and a smooth, sleek beard. He had a small head and a big paunch that jounced whenever he laughed. But today, he just sat there, sullen-faced, greeting no one and saying nothing.

“Who could be absolutely sure? Who?” Saad looked up and saw the tall thin man passing in front of him, pacing back and forth muttering these words to himself. As he walked he raised his shoulders so high that they almost reached his ears. One of the two men sitting down yelled out to him, “You’re making us dizzy. Why don’t you calm down and sit like everyone else?” But the man paid no attention and kept pacing and muttering to himself.“

Radwa Ashour (26 mei 1946 – 30 november 2014)

De Belgische schrijver Hugo Raes werd geboren in Antwerpen op 26 mei 1929. Zie ook alle tags voor Hugo Raes op dit blog.

Uit: Het jarenspel

“Berichten uit onze dierbare wereld

Nooit aflatend ratelt de telex in zijn glazen cabine, een robot in ononderbroken monoloog, die probeert te communiceren met de buitenwereld. En er eigenlijk in slaagt.

Als William er binnen gaat en het lint afscheurt, lijkt het of de telexmachine zijn stem verheft. Hij tatert luider dan je hem kan horen als de glazen deur van zijn hok dichtvalt. En William converseert met hem. Het is een oude gewoonte. De communication gap die je met de anderen hebt, kun je opheffen met deze beroepsheraut met de roepnaam R – van Rank – en X – van Xerox – 302. Vele mensen converseren met hun hond, een parkiet, een schildpad, zelfs met hun vissen in het aquarium. Zolang er leven is, is er conversatie, want niemand zal bijvoorbeeld praten tegen een dode vis, hoewel een rondzwemmende even stom is als een soortgenoot die in de pan ligt, of op je bord. Patsy praat tegen alle dieren. Er kan er geen in de buurt zijn, of ze is in gesprek: Dag schoonheid, wil jij een klontje? Maar ik heb er geen bij me. Of misschien heb ik er toch nog eentje in mijn handtas. Eentje van de café-filtre in het restaurant. Want die neemt ze altijd mee. Ook het chocolaatje of koekje erbij. Slecht voor de lijn. Bovendien aardige besparing: hoeft haast nooit suiker te kopen, William neemt er maar eentje in zijn thee. Per kop. Koffie vindt hij een probaat braakmiddel, drinkt het soms, vlug, met opgetrokken neus, twee koppen achter elkaar, als ie snel wakker wil zijn, of opgejut voor het werk. Vroeger wou Pat slechts koffie drinken, thee vond zij afwaswater.

Het paard antwoordt met een jaknikken. Ja hoor, je krijgt er eentje, bemoedert Pat, een klontje uit haar tas opdiepend. Nog steeds begrijpt Wim het verschijnsel handtas niet. Nieuwsgierig onderwerpt hij haar handtas geregeld aan een onderzoek. Blijf uit mijn tas, roept ze dan, maar hij wil de mysteries ervan kennen. Soms vindt hij zaken die hij in maanden niet meer heeft gezien of verloren waande: een pennemesje van hem, zijn nagelknipper, twee nagelknippers, een menukaart van een feestje of een restaurant ergens, menigvuldige potjes, tubes, kortingzegeltjes, kalendertjes, een publicitair cadeautje in de vorm van een plastic mapje, een mini-rolmeter, een mini-zaklampje, en mooi verpakte klontjes en speculaasjes. Even grote schoonmaak houden, deelt hij mee. Het paard groet en dankt met een stem die aan hinniken doet denken. De hond bemoedert ze, kom eens bij mama, zegt ze, of: is pappie stout? – Zijn moeder praat tegen haar tv. Er grijpt iets plaats in een feuilleton, en zijn moeder geeft luidop, in haar eentje in de kamer, commentaar, zegt haar mening, geeft haar afkeuring ten beste of haar waardering. Geeft soms een kernachtig antwoord op een laatdunkend verwijt, dat één van de hoofdpersonen formuleert.”

Hugo Raes (26 mei 1929 – 23 september 2013)

De Tsjechische dichter en vertaler Vítezslav Nezval werd geboren op 26 mei 1900 in Biskoupky. Zie ook alle tags voor Vítězslav Nezval op dit blog.

Pocket Handkerchief

I’m taking off today; I feel like crying—

Just time to wave my handkerchief, I see;

If all the world were one great gaudy poster,

Cynic, I’d tear it, throw it in the sea.

Just like a fish, this vale of tears absorbed me,

Its image, broken thirty times, composed;

Now leave me, skylark, your great glorious error,

If I must sing, I’d sob a bit, one knows.

The kerchief flutters down; the city opens—

Grotesquely, at the tunnel’s mouth, it breaks;

A pity death’s not just a long black journey,

From which, in some unknown hotel, I’d wake.

You whom I loved like Andrea del Sarto,

Turn a silk kerchief for fair women’s eyes;

And, if you know death’s just a leap, a moment—

Don’t flinch, now—Good day, goshawk!—up one flies!

Vertaald door Susan Reynolds

A City Of Towers

O hundred-towered Prague

city with fingers of all the saints

with fingers made for swearing falsely

with fingers from the fire & hail

with a musician’s fingers with shining fingers

of a woman lying on her back

With fingers of asparagus

with fingers with fevers of 105 degrees

with fingers of frozen forest & with fingers without gloves

with fingers on which a bee has landed

with fingers of blue spruces

With fingers disfigured by arthritis

with fingers of strawberries

with spring water fingers & with fingers of bamboo

Vertaald door Jerome Rothenberg en Milos Sovak

Vítězslav Nezval (26 mei 1900 – 6 april 1958)

Borstbeeld door Vladislav Turský in de Prague City Gallery

De Belgische, Franstalige, schrijver en essayist Ivan O. Godfroid werd geboren in Boussu op 26 mei 1971. Zie ook alle tags voor Ivan O. Godfroid op dit blog.

Uit: Maîtriser, c’est lâcher prise

« Neuf cents ans – jour pour jour – avant que je ne vienne au monde, naissait un certain comte de Poitiers, dont le destin sera, ni plus ni moins, de fonder la littérature française. Il s’agit probablement de Guillaume IX d’Aquitaine (1071-1126), mais jusqu’à l’identité exacte de ce premier troubadour demeure incertaine. De lui, il ne nous est parvenu que dix œuvres, dont la plus saisissante s’intitule : « Poème sur pur néant » ; sept strophes de six vers dont le thème esquisse une confession fataliste sur la vanité des choses. Ainsi, au moment même où naît la littérature francophone, elle engendre d’emblée une œuvre d’une modernité absolue. Ce « Farai un vers de dreit nien » est gothique, désabusé, et aussi formidablement nihiliste… Sa lecture m’a laissé sans voix. Pourquoi écrire encore?

Pourquoi écrire encore, en effet, après la clôture du cycle de « L’Ombre close des portes celtiques » ? Pourquoi écrire encore, alors que j’ai réuni dans un roman – « La Quintessence de mes jours sous un ciel couvert » – tout ce que j’espérais apporter de beau et d’original à la littérature ? Ce thriller littéraire repose sur un nombre important d’aphorismes inédits, et fait la part belle aux dictons, aux proverbes du monde entier. Il se clôture sur le constat que le roman n’est plus adapté à la littérature du XXIe siècle – non pas qu’il ne plaira plus à quiconque, mais plutôt que son lectorat inconditionnel sera désormais en constante régression. Il faut autre chose.

Cette « autre chose », cette littérature directe, complexe tout autant qu’accessible et immédiate, c’est précisément l’aphorisme – l’huile essentielle de rébellion. Un aphorisme qui ne dit pas son nom. Un aphorisme qui, de l’Antiquité d’un Confucius aux derniers buzz des réseaux sociaux, a traversé les âges pour finalement s’imposer comme la forme ultime de littérature. Une littérature véritablement universelle.”

Ivan O. Godfroid (Boussu, 26 mei 1971)

De Amerikaanse dichter en schrijver Maxwell Bodenheim werd geboren op 26 mei 1892 in Hermanville, Mississippi. Zie ook alle tags voor Maxwell Bodenheim op dit blog.

South State Street: Chicago (Fragment)

Undisturbed by joy or hatred.

At her side two factory girls

In slyly jaunty hats and swaggering coats,

Weave a twinkling summer with their words:

A summer where the night parades

Rakishly, and like a gold Beau Brummel.

With a gnome-like impudence

They thrust their little, pink tongues out

At men who sidle past.

To them, the frantic dinginess of day

Has melted to caressing restlessness

Tingling with the pride of beasts and hips.

At their side two dainty, languid girls

Playing with their suavely tangled dresses,

Touch the black crowd with unsearching eyes.

But the old man on the corner,

Bending over his cane like some tired warrior

Resting on a sword, peers at the crowd

With the smouldering disdain

Of a King whipped out of his domain.

For a moment he smiles uncertainly.

Then wears a look of frail sternness.

Musty. Rabelaisian odours stray

From this naïvely gilded family-entrance

And make the body of a vagrant

Quiver as though unseen roses grazed him.

His face is blackly stubbled emptiness

Swerving to the rotted prayers of eyes.

Yet, sometimes his thin arm leaps out

And hangs a moment in the air,

As though he raised a violin of hate

And lacked the strength to play it.

A woman lurches from the family-entrance.

With tense solicitude she hugs

Her can of beer against her stunted bosom

And mumbles to herself.

The trampled blasphemy upon her face

Holds up, in death, its watery, barren eyes.

Indifferently, she brushes past the vagrant:

Life has peeled away her sense of touch.

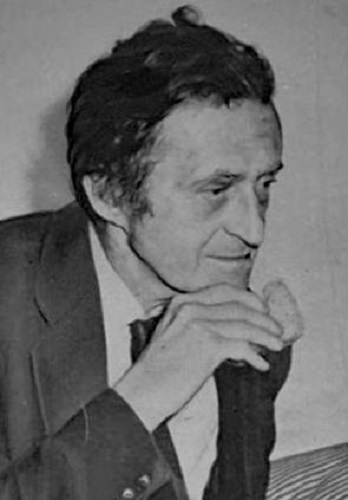

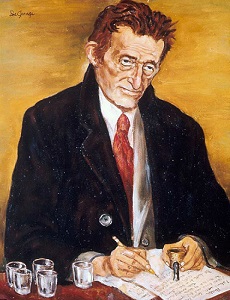

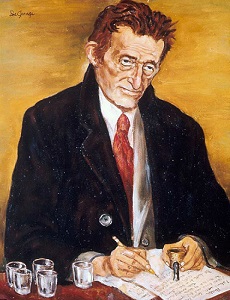

Maxwell Bodenheim (26 mei 1892 – 6 februari 1954)

Portret door Leonard De Grange, ca. 1950

De Duitse schrijfster Isabella Nadolny (eig. Isabella Peltzer) werd geboren op 26 mei 1917 in München. Zie ook alle tags voor Isabella Nadolny op dit blog.

Uit: Ein Baum wächst übers Dach

„Leo schlug noch einen kleinen Vorratskeller vor, in den man von der Küche aus durch eine Klappe im Fußboden hinunterstieg, kaum größer als ein Schrank, aber gleichmäßig temperiert.

»Wozu denn?«

»Für die Äpfel!«

»Die sind doch erst im September reif, da sind wir doch längst wieder in der Stadt«, wandte ich ein.

»Man kann nie wissen«, sagte Bruder Leo und schraffierte die Fußbodenklappe in den Küchengrundriß hinein.

Dies wäre der Augenblick gewesen, in dem ich hätte ahnungsvoll erschauern müssen. In Wagneropern erklingt jeweils das passende Motiv, damit auch diejenigen erschauern können, die den Text nicht rechtzeitig verstanden haben. Im Leben ist das anders. Insbesondere bei mir. Ich erkenne mein Schicksal niemals, auch dann nicht, wenn es sozusagen schon mitten im Zimmer steht.

So verabschiedete ich mich denn mit einem Kuß von Mama, ahnungslos, daß meine Zukunft schon begonnen hatte, und kehrte zu meinen wichtigen Privatangelegenheiten zurück.

Die Privatangelegenheiten eines Backfisches sind ebenso albern wie unüberschaubar: Ich stritt mich mit Freundinnen wegen nichts und wieder nichts, wartete atemlos auf Anrufe eines Tanzstundenjünglings, schrieb Aufsätze über Themen, von denen ich nichts verstand, zum Beispiel ›Alles hohe Leben quillt aus Opfern‹, trug eine Mickymaus am Mantelaufschlag und konnte von Mama nur mit Mühe zurückgehalten werden, mir bei Sally Marx in der Barer Straße einen Halbschleier zu kaufen, um meiner Baskenmütze etwas Dämonisches zu geben.“

Isabella Nadolny (26 mei 1917 – 31 juli 2004)

Cover

De Franse schrijver Edmond de Goncourt werd geboren op 26 mei 1822. Zie ook alle tags voor Edmond de Goncourt op dit blog.

Uit: De broeders Zemganno (Vertaald door J. Kuijlman)

“Buiten, op het land, aan den voet van een octrooipaal, kwamen vier wegen samen. De eerste, die liep voor langs een modern kasteel in den stijl van Lodewijk XIII, waar juist de eerste etensbel luidde, schoof met wijde om-kronkelingen een steilen berg op. De tweede bezoomd door noteboomen, en die twintig schreden verder een slecht-begaanbare zij weg wend, verloor zich tusschen heuvels, naakt van top en lager met wijn -stokken beplant. De vierde liep dicht langs steengroeven, waarbij men hier en daar ijzeren horren, om het fijne zand to zeeven, en stortkarren met gebroken wielen zag staan. Deze weg waarop de drie andere uitliepen, leidde over een brug, sonoor klinkend onder de wagens, naar een stadje, amphitheatersgewijze gebouwd op de rotsen achter de groote rivier, waarvan een kromming, dwars door jonge aanplantingen loopend, het uiteinde van een weiland besproeide, dat zich tot over het kruispunt uitstrekte. Vogels vlogen met vleugelreppen door de zich nog in zonlicht badende lucht, met zachte kreten van den gouden dag afscheid nemend. Het werd koel in de schaduw der boomen en er kwam violet-kleur in de wagensporen der wegen. Men hoorde nog slechts van heel verre de klacht van een vermoeide wagenas.

Groote stilte steeg op uit de velden, tot den volgenden dag van alle menschelijke leven ledig en verlaten, Zelfs de rivier, waarvan slechts de rimpels merkbaar waren rondom een tak die afhing in het water, scheen hare vlugge vloeiing te verliezen en het leek wel, of de stroom al voortglij dend, uitrustte. Toen, met een oudijzer-klank als van een defecte rem, werd op den kronkelenden weg, die den berg afdaalde, eene vreemdsoortige ,kermiswagen” zichtbaar, bespannen met een wit, dampig paard. Het was een kolossale wagen, met over den kap roestig zink, beschilderd met een breeden rand oranje, en die van voren een soort portiekje had, waar omheen klimop, geplant in een gelapte kookketel, een lijst legde van trekkend groen, dat been en weer schudde bij iederen schok. Deze wagen werd spoedig gevolgd door een bizarre groene kar, waarvan het bovengedeelte voorzien van een dak, boven de raderen, zich verwij dde en uitbuikte op de wij ze van de breede flanken der stoombooten.”

Edmond De Goncourt (26 mei 1822 – 16 juli 1896)

Cover van een Franse uitgave uit 1909