De Argentijnse schrijfster Luisa Valenzuela werd geboren op 26 november 1938 in Buenos Aires. Zie ook alle tags voor Luisa Valenzuela op dit blog.

Uit: Strange things happen here (Vertaald door Helen lane)

“He sure needed a jacket like this one, a sports jacket, well lined, lined with cash not silk who titres about silk? With the booty in hand they head back home. They don’t have the nerve to take out one of the crisp bills that Mario thought he had glimpsed when he opened the briefcase just a hair-spare change to take a taxi or a stinking bus. They keep an eye peeled to see whether the strange things that are going on hem, the things they happened to overhear in the cafe, have something to do with their two finds. The strange characters either haven’t appeared in this part of town or have been replaced: two policemen per corner an too many because them are lots of corners. This is not a gray afternoon like any other, and come to think of it maybe it isn’t even a lucky afternoon the way it appears to be. These are the blank faces of a weekday, so different from the blank faces on Sunday. Pedro and Mario have a color now, they have a . mask and can feel themselves exist because a briefcase (ugly word) and a sports jacket blossomed in their path. (A jacket that’s not as new as it appeared to be-threadbare but respectable. That’s it: a respectable jacket.) As afternoons go, this isn’t an easy one. Something is moving in the air with the howl of the sirens and they’re beginning to feel fingered. They see police everywhere, police in the dark hallways, in pairs on all the corners in the city, police bouncing up and down on their motorcycles against traffic as though the proper functioning of the country depended on them, as maybe it does, yes, that’s why things are as they are and Mario doesn’t dare say that aloud because the briefcase has him tongue-tied, not that there’s a microphone concealed in it, but what paranoia, when nobody ’s forcing him to carry it! He could get rid of it in some dark alley-but how can you let go of a fortune that’s practically fallen in your lap, even if the fortune’s got a load of dynamite inside? He takes a more natural grip on the briefcase, holds it affectionately, not as though it were about to explode. At this same moment Pedro decides to put the jacket on and it’s a little too big for him but not ridiculous, no not at all. Loose-fitting, yes, but not ridiculous; comfortable, warm, affectionate, just a little bit frayed at the edges, worn. Pedro puts his hands in the pockets of the jacket (his pockets) and discovers a few old bus tickets, a dirty handkerchief, several bills, and some coins. He can’t bring himself to say anything to Mario and suddenly he turns around to see if they’re being followed. Maybe they’ve fallen into some sort of trap, and Mario must be feeling the same way because he isn’t saying a word either. He’s whistling between his teeth with the expression of a guy who’s been carrying around a ridiculous black briefcase like this all his life. The situation doesn’t seem quite as bright as it did in the beginning.”

Luisa Valenzuela (Buenos Aires, 26 november 1938)

De Frans-Roemeense schrijver Eugène Ionesco werd geboren op 26 november 1912 in Slatina, Roemenië. Zie ook alle tags voor Eugène Ionesco op dit blog.

Uit: Rhinocéros (Vertaald door Derek Prouse)

“JEAN: It’s different with me. I don’t like waiting; I’ve no time to waste. And as you’re never on time, I come late on purpose—at a time when I presume you’ll be there.

BERENGER: You’re right … quite right, but …

JEAN: Now don’t try to pretend you’re ever on time!

BERENGER: No, of course not … I wouldn’t say that.

[JEAN and BERENGER have sat down.]

JEAN: There you are, you see!

BERENGER: What are you drinking?

JEAN: You mean to say you’ve got a thirst even at this time in the morning?

BERENGER: It’s so hot and dry.

JEAN: The more you drink the thirstier you get, popular science tells us that…

BERENGER: It would be less dry, and we’d be less thirsty, if they’d invent us some scientific clouds in the sky.

JEAN: [studying BERENGER closely] That wouldn’t help you any. You’re not thirsty for water, Berenger

BERENGER: I don’t understand what you mean.

JEAN: You know perfectly well what I mean. I’m talking about your parched throat. That’s a territory that can’t get enough!

BERENGER: To compare my throat to a piece of land seems,..

JEAN: [interrupting him] You’re in a bad way, my friend.

BERENGER: In a bad way? You think so?

JEAN: I’m not blind, you know. You’re dropping with fatigue. You’ve gone without your sleep again, you yawn all the time, you’re dead-tired … “

Eugène Ionesco (26 november 1912 – 28 maart 1994)

Scene uit een opvoering in Brussel, 2016

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Marilynne Robinson werd geboren in Sandpoint, Idaho op 26 november 1943. Zie ook alle tags voor Marilynne Robonson op dit blog.

Uit: Gilead

“My grandfather seemed to me stricken and afflicted, and indeed he was, like a man everlastingly struck by lightning, so that there was an ashiness about his clothes and his hair never settled and his eye had a look of tragic alarm when he wasn’t actually sleeping. He was the most unreposeful human being I ever knew, except for certain of his friends. All of them could sit on their heels into their old age, and they’d do it by preference, as if they had a grudge against furniture. They had no flesh on them at all. They were like the Hebrew prophets in some unwilling retirement, or like the primitive church still waiting to judge the angels. There was one old fellow whose blessing and baptizing hand had a twist burned into it because he had taken hold of a young Jayhawker’s gun by the barrel. ‘I thought, That child doesn’t want to shoot me,’ he would say. ‘He was five years shy of a whisker. He should have been home with his mama. So I said, “Just give me that thing,” and he did, grinning a little as he did it. I couldn’t drop the gun – I thought that might be the joke – and I couldn’t shift it to the other hand because that arm was in a sling. So I just walked off with it.’ They had been to Lane and Oberlin, and they knew their Hebrew and their Greek and their Locke and their Milton. Some of them even set up a nice little college in Tabor. It lasted quite a while. The people who graduated from it, especially the young women, would go by themselves to the other side of the earth as teachers and missionaries and come back decades later to tell us about Turkey and Korea. Still, they were bodacious old men, the lot of them. It was the most natural thing in the world that my grandfather’s grave would look like a place where someone had tried to smother a fire.

Just now I was listening to a song on the radio, standing there swaying to it a little, I guess, because your mother saw me from the hallway and she said, ‘I could show you how to do that.’ She came and put her arms around me and put her head on my shoulder, and after a while she said, in the gentlest voice you could ever imagine, ‘Why’d you have to be so damn old?’ I ask myself the same question.

A few days ago you and your mother came home with flowers. I knew where you had been. Of course she takes you up there, to get you a little used to the place. And I hear she’s made it very pretty, too. She’s a thoughtful woman. You had honeysuckle, and you showed me how to suck the nectar out of the blossoms. You would bite the little tip off a flower and then hand it to me, and I pretended I didn’t know how to go about it, and I would put the whole flower in my mouth, and pretend to chew it and swallow it, or I’d act as if it were a little whistle and try to blow through it, and you’d laugh and laugh and say, No! no! no!! And then I pretended I had a bee buzzing around in my mouth, and you said, ‘No, you don’t, there wasn’t any bee!’ and I grabbed you around the shoulders and blew into your ear and you jumped up as though you thought maybe there was a bee after all, and you laughed, and then you got serious and you said, ‘I want you to do this.’ And then you put your hand on my cheek and touched the flower to my lips, so gently and carefully, and said, ‘Now sip.’ You said, ‘You have to take your medicine.’ So I did, and it tasted exactly like honeysuckle, just the way it did when I was your age and it seemed to grow on every fence post and porch railing in creation.”

Marilynne Robinson (Sandpoint, 26 november 1943)

De Nederlandse dichter Herman Gorter werd geboren in Wormerveer op 26 november 1864. Zie ook alle tags voor Herman Gorter op dit blog.

Uit de donkere aarde …

Uit de donkere aarde

Komt op het licht,

En het Heelal zweeft in het licht

Der Liefde.

Gij ligt in ’t licht der Eeuwigheid,

In dat licht, dat zich om ons breidt,

Zweef ik.

O niet van mij het licht,

Dat zich over u breidt,

Het is, het is het licht

Der Eeuwigheid.

O niet van u het licht,

Dat zich uit u verspreidt,

Het is, het is het licht

Der Liefde der Eeuwigheid.

Gij ligt daarin,

Ik zweef daarin.

Uit: Mei

Toen luider lachend wentelde hij rond

En zwom naar boven door den waterval

Van schuim en sneeuw, die drijft in ieder dal

Tusschen twee waterbergen, zie, hij ligt

Nest’lend in kroezig water, ’n wiegewicht

Door moeder pas gewasschen in haar schoot;

Het drijft van ronde druppels, overrood

Reiken de armpjes, uit het mondje gaat

Gekraai; zoo dreef hij, in het bol gelaat

Tusschen de lippen in, de gouden kelk,

Fontein van gouden klanken, een vaas melk-

Wit was hij drijvend met gemengden wijn,

Vurig rood blozend door het porselein.

Nu zetelt hij in ’t water, baar na baar

Ziet hij al lachend rijzen na elkaar,

Daar schatert hij en spant den blanken arm,

En door het water gaat een luid alarm.

Toen werd de zee wel als een groot zwaar man

Van vroeger eeuw en kleding, rijker dan

Nu in dit land zijn: bruin fluweel en zij

Als zilver en zwart vilt en pelterij

Vèr uit Siberisch Rusland; geel koper

Brandt vele lichtjes in de plooien der

Hoozen, in knoopen en in passement

Van het breed overkleed, wijd uithangend.

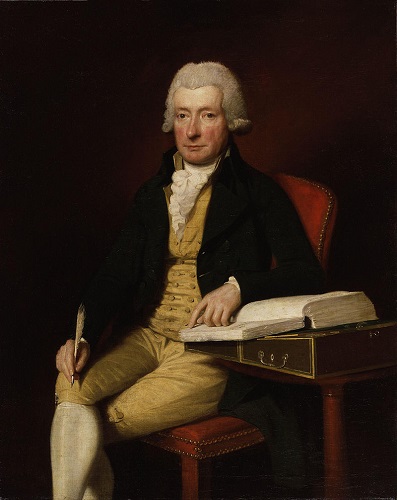

Herman Gorter (26 november 1864 – 15 september 1927)

Portret, waarschijnlijk door Thérèse Schwartze, ca. 1883

De Nederlandse dichter, criticus, essayist en vertaler Paul Thomas Basilius Rodenko werd geboren in Den Haag op 26 november 1920. Zie ook alle tags voor Paul Rodenko op dit blog.

Prelude tot een Oekraïns epos

Stormen jagen over de steppe

junckers jagen over de steppe

dorpen schuiven klagende

in hun foedraal

van rook

Wie zal de gitaar van mijn ziel bespelen

wie zal de gitaar van mijn dorp bespelen

een meisjeshand

heeft zeven snaren doorgeknipt

ze zijn gesprongen met een klein geluid van eksters.

Jij-Mei

Ik mors je over al mijn paden liefste

Jij rood de rozen en jij blinkende het blauw

Jij kano’s in de blik van elke vrouw

Jij beelden in parijzen van het water

Jij lentebroden in de manden van de straten

Jij kinderen die met een hoofdvol mussen

Achter de zonnebal aandraven

Jij mei jij wij

Jij herteknieën van de zuidenwind

Ik juich je sterrelings

Laatseptembermorgenlicht

Gedaagd in kort geding

Straalsgewijs ondervraagd

Staat ’t nachtelijkste ding

Met potenvol vandaag

Het lichtrequisitoir

Maakt alles recht en klaar

Vaas liefste en trompet

Zijn bij elkaar gezet

Naar ninivehse wet

Van ’t onontkoombaar daar

Paul Rodenko (26 november 1920 – 9 juni 1976)

De Hongaarse dichter, schrijver en vertaler Mihály Babits werd geboren op 26 november 1883 in Szekszárd. Zie ook alle tags voor Mihály Babits op dit blog.

Zigeunerlied (Fragment)

‘Bündel an den Zweig geschwind,

schaukle nur, Zigeunerkind!

Maulbeerliebchen, schlafe ein,

winziges Zigeunerlein!

Wandern wirst durch dunkle Wälder,

schlechte Felder, gute Felder,

dir ist jedes Land egal,

Himmelblau gibt’s überall.

Bist in Busch und Strauch geboren,

hätt dich fast im Moos verloren.

Wie die Samen, die verwehen,

wirst du von der Mutter gehen,

vaterlos, mutterlos,

wandre nur, die Welt ist groß!

Gruselmärchen, lust’ge Lieder

singe ich dir immer wieder.

Winz’ge Seele, Maulbeerschätzchen,

überall gibt’s gute Plätzchen.

Kommt manchmal ein böser Wind,

fürcht dich nicht, Zigeunerkind.

Feuer gibt der trockne Ast,

wärmt dich bis zum Frühjahr fast.

Schlechte Ernte stöhnt der Bauer,

Dürre macht sein Leben sauer.

Kümmert’s dich? Auf keinen Fall.

Schatten gibt es überall.

Wandern will durch dunkle Wälder,

schlechte Felder, gute Felder,

dir ist jedes Land egal,

Himmelblau gibt’s überall.

Kommt der Jude durch den Wald,

schau dich um und schreie: halt!

Findst du eine Schöne hier,

fragst nicht lange, nimm sie dir.

Bist in Busch und Strauch geboren,

hätt dich fast im Moos verloren.

Wie die Samen, die verwehen,

wirst du von der Mutter gehen,

vaterlos, mutterlos, wandre nur,

die Welt ist groß!’

Mihály Babits (26 november 1883 – 4 augustus 1941)

Standbeeld in Szekszárd

De Vlaamse dichter, schrijver en columnist Louis Verbeeck werd geboren in Tessenderlo op 26 november 1932. Zie ook alle tags voor Louis Verbeeck op dit blog.

Uit: Roots (Column)

“Ze beginnen dat allemaal zo’n beetje in te zien, dat je terug naar je ‘roots’ moet. ‘Back to the basics’ zeggen sommigen, maar het komt er gewoon op neer, dat je niet moogt vergeten waar je vandaan komt.

Dus ging ik ook nog eens terug naar mijn dorp en ik dacht: ‘Ik rijd tot aan de zandberg, daar parkeer ik mijn auto en dan zien we we’l. En ik had en petje bij en een zonnebril, want ik wilde het incognito houden. De zandberg was er nog, maar wat in de tijd van mijn roots en mijn verbeelding misschien een grote zandbak geweest was, een soort van Sahara met veel bergop, daar schoot niet veel meer van over.

Er was wel van alles bijgekomen, een stuk of vijf “oases” waar je er uitgebreid kon voor zorgen dat je ‘roots’, je wortels dus, niet van droogte en van dorst zouden omkomen. Er was zelfs een terras, en ik dacht: daar ga ik even zitten om eens grondig te bekijken wat er van mijn roots overgebleven is.

Ik had nog maar net een leeg tafeltje gevonden, toen er een enthousiaste inboorling op mij toekwam en mij verrast vertelde wie ik was, zelfs met petje en onherkenbare zonnebril. Hij had dwars door mijn camouflage heen gekeken.

“Ken je mij niet meer?” vroeg hij, en hij zei dat hij Frans was, Sus, gelijk ze zeien en dat hij getrouwd was met Adeline. En Adeline, die had ik toch zeker nog gekend want die woonde vroeger vlak in mijn buurt, en als hij zich niet vergiste was Adeline nog zo’n beetje een oude vlam van mij geweest. “Grapje” lachte hij, “maar vroeger vertelde ze dat jullie samen in de muziekschool gezeten hadden, en vioolles gevolgd. Bij meester Job.”

Ik zette de camera van mijn roots wat scherper en jawel, Adeline kwam langzaam in beeld. Hij zei dat hij begreep dat ik me haar zo dadelijk niet herinnerde, ik was niet zo jong meer, hij trouwens ook niet, en het was allemaal zo lang geleden.”

Louis Verbeeck (26 november 1932 – 25 november 2017)

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata

De Duitse schrijver Alyosha Brell werd geboren in 1980 in Wesel. Zie ook alle tags voor Alyosha Brell op dit blog.

Uit: Kress

„Er hätte mehr sparen müssen, dachte Kress, während er sich an einen Gummiriemen geklammert von der U-Bahn durchschütteln ließ. Beispielsweise die schöne, historisch-kritische Hamburger Goethe-Ausgabe: Die hätte, strenggenommen, nicht sein müssen. Anderseits, er war nun einmal ein Goethe-Forscher, beziehungsweise beabsichtigte ein solcher zu werden, und die Hamburger Goethe-Ausgabe gehörte zum Goethe-Forscher wie der Fleischerhammer zum Fleischer. Die Hamburger Goethe-Ausgabe war, bei Lichte betrachtet, sogar unbedingt notwendig gewesen, daran war nicht zu rütteln, dort zu sparen wäre unvernünftig, wäre perspektivisch sogar berufsschädigend gewesen. Wirklich, U-Bahn-Fahren war das Letzte! Er hasste es, Schulter an Schulter mit all diesen Leuten stehen zu müssen, eingepfercht wie Schlachtvieh in einen Tiertransporter. Dienstagmorgens war die Situation besonders fatal. Dienstagmorgens krochen all jene Studenten aus ihren Löchern, die am Montag ihren Rausch vom Wochenende auszuschlafen pflegten. Mittwochmorgens entspannte sich die Lage ein wenig, weil die Studenten empfanden, bereits am Dienstag etwas geleistet und sich daher eine Pause verdient zu haben, und am Donnerstag war im Grunde schon Wochenende und Kress hatte die U-Bahn mehr oder minder für sich. Jetzt aber war erst einmal Dienstag und die Enge kaum auszuhalten. Er hatte sich einen strategisch günstigen Platz an einer Plexiglaswand neben der Tür gesichert. Direkt vor ihm, keine Fingerlänge entfernt, standen zwei Frauen und erzählten einander in großer Ausführlichkeit von den Aventüren, die ihnen am Wochenende widerfahren waren. »Und denn«, sagte die eine, »waren wir was trinken im Alhambra, und denn …« Kress hatte das Gefühl, vom bloßen Zuhören dümmer zu werden. Ein Leuchtturm war er, einsam Wacht haltend auf dem Felsen der Exzellenz. Dagegen brandete die Gischt der Banalität. Entsprechend froh war er, als am U-Bahnhof Dahlem-Dorf die Türen aufglitten und die Meute aus dem Waggon ins Freie drängte. Augenblicklich rempelte er sich an die Spitze der Bewegung. Es war ungewöhnlich warm für diese Jahreszeit, seit über einer Woche hatte sich am Himmel keine Wolke sehen lassen, und die Studenten, an denen er jetzt vorüberstapfte, hätten luftiger nicht gekleidet sein können: in kurze Hosen und T-Shirts und Röcke, aus denen die über lange Wintermonate entfärbten Glieder staken wie die weißen Tentakel von Tiefseequallen.“

Alyosha Brell (Wesel, 1980)

De Omaanse dichter Mohamed Al-Harthy werd geboren in al-Mudhayrib, Oman, in 1962. Zie ook alle tags voor Mohamed Al-Harthy op dit blog.

The Angel’s Whistling

Who are you reflected in the verse?

Its beginning

or its end

on the flowing page?

And what if, for all the controversy,

you really were its mirror?—Would the holy verse’s mantle

be cast off? Would all hell break loose?

Or would the angel’s whistling

hold hell off

until the star sees itself

reflected on the watery page,

reflected on the sea of words

before the tide brings the verse back?

One could read it

from top to bottom

(and not from right to left)

to prolong reflection’s game . . .

But who are you in these mirrors?

Who are you reflected on the page

once the tide’s gone out again?

Its beginning or its end?

Who are you when the words open

their crocodile jaws

to swallow a shining star? . . .

It might shine a few moments,

it might shine forever—but you,

you will not see its reflection

once the tide’s flowed on

to the next verse.

Vertaald door Kareem James Abu-Zeid

Mohamed Al-Harthy (al-Mudhayrib, 1962)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 26e november ook mijn blog van 26 november 2017 deel 2 en eveneens deel 3.