De Japanse schrijver Kazuo Ishiguro werd op 8 november 1954 geboren in Nagasaki. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 november 2006 en ook mijn blog van 8 november 2007.

Uit: When We Were Orphans

“It was the summer of 1923, the summer I came down from Cambridge, when despite my aunt’s wishes that I return to Shropshire, I decided my future lay in the capital and took up a small flat at Number 14b Bedford Gardens in Kensington. I remember it now as the most wonderful of summers. After years of being surrounded by fellows, both at school and at Cambridge, I took great pleasure in my own company. I enjoyed the London parks, the quiet of the Reading Room at the British Museum; I indulged entire afternoons strolling the streets of Kensington, outlining to myself plans for my future, pausing once in a while to admire how here in England, even in the midst of such a great city, creepers and ivy are to be found clinging to the fronts of fine houses.

It was on one such leisurely walk that I encountered quite by chance an old schoolfriend, James Osbourne, and discovering him to be a neighbour, suggested he call on me when he was next passing. Although at that point I had yet to receive a single visitor in my rooms, I issued my invitation with confidence, having chosen the premises with some care. The rent was not high, but my landlady had furnished the place in a tasteful manner that evoked an unhurried Victorian past; the drawing room, which received plenty of sun throughout the first half of the day, contained an ageing sofa as well as two snug armchairs, an antique sideboard and an oak bookcase filled with crumbling encyclopaedias — all of which I was convinced would win the approval of any visitor. Moreover, almost immediately upon taking the rooms, I had walked over to Knightsbridge and acquired there a Queen Anne tea service, several packets of fine teas, and a large tin of biscuits. So when Osbourne did happen along one morning a few days later, I was able to serve out the refreshments with an assurance that never once permitted him to suppose he was my first guest.”

Kazuo Ishiguro (Nagasaki, 8 november 1954)

De Duitse schrijver Peter Weiss werd geboren op 8 november 1916 in Nowawes (het tegenwoordige Neubabelsberg) bij Berlijn. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 november 2006.

Uit: Die Ästhetik des Widerstands

„Unsre Kultur, das ist das Tragen, Ziehn und Heben, das Aneinanderknüpfen und Befestigen. Diese Kultur tritt mir entgegen, sagte er [mein Vater], wenn ich sehe, wie einer das gehackte Holz aufschichtet, die Sense schleift, das Netz flickt, die Balken zum Dachstuhl zusammenfügt, die Kolben der Maschine poliert. Er wolle dies nicht idealisieren, fügte er hinzu, aber er sehe keine andre Möglichkeit, etwas von dem wachzurufen, was uns mit der Gesamtheit von Können und Wissen einer Epoche verbinde. Das Merkwürdige sei ja, sagte er, dass erst die künstlerische Abbildung eine

r Näherin, einer Spitzenklöpplerin, eines Mähers und Dreschers, einer Magd bei der Traubenernte oder eines Schmieds unsrer Arbeit einen Wert verleiht. Nur im Kunstwerk besäße die Arbeit kulturelle Bedeutung, dort sei sie zu Kunst geworden, während die Ausführenden ranglos blieben. Ich entsann mich dieses Gesprächs so deutlich, weil es zusammenhing wiederum mit einem Bild, dem zweieinhalb Meter breiten Gemälde des Eisenwalzwerks von Menzel. Anhand eines Farbdrucks hatte mein Vater mir erklärt, wie jetzt, da durch das Heranwachsen einer bewussten Arbeiterklasse auch in der anerkannten offiziellen Kunst ein Platz für sie eingeräumt wurde, auf dem sie sich zur Geltung bringen durfte, und wie gleichzeitig die Großzügigkeit des Etablissements mit geschickter Handhabung zurückgenommen wurde. Allgemein wurde dieses Bild, dessen Original wir uns später in der Nationalgalerie ansahn, eine Apotheose der Arbeit genannt. Die Atmosphäre der Schwerindustrie war überzeugend mit großer technischer Sachkenntnis wiedergegeben worden. Der Dampf, das Dröhnen der Hämmer, das Kreischen der Kräne und Zugketten, das Rotieren der Schwungräder an den Maschinen, die Hitze der Feuer, die Weißglut des Eisens, die Anspannung der Muskeln, dies alles war in der Malerei zu verspüren. Zum Bildzentrum hin schob die Gruppe der Schmiede den glühenden Metallblock vom angehobnen Karren unter die Walze, rechts, abgedeckt durch eine zerbeulte Blechscheibe, zusammengesunken unter Rohren und Ketten, rasteten ein paar Männer, löffelten aus Näpfen, hoben eine Flasche zum Mund, und am linken Bildrand, mit nacktem Oberkörper, wuschen sich Leute der abgelösten Schicht Hals und Haare. jede Handhabung, jede Drehung und Beugung über den Werkzeugen und auch das müde, erschlaffte Dasitzen in der Ecke war Bestandteil der riesigen Halle, eingezwängt in das Gestänge, das Tageslicht, das entfernt an ein paar Stellen durch den Dunst schimmerte, schien unerreichbar. Die Schilderung dieses unaufhörlichen, verschwitzten Ineinandergreifens sagte nichts andres aus, als dass hier hart und widerspruchslos gearbeitet wurde. Die Wucht im Hochstemmen und Ausschwingen, geregelt und beherrscht, der Augenblick größter Konzentration beim Griff um die Zangen, die Wachsamkeit des bärtigen Vorarbeiters am Hebel, beim Entgegennehmen des Walzstücks, das Abschrubben der verrußten Körper, das Erloschensein in kurzer Pause, wies auf ein einziges Thema hin, auf die Arbeit, auf das Prinzip der Arbeit, und es war ein bestimmtes Prinzip, dessen Art sich erst nach eingehender Beobachtung definieren ließ.“

Peter Weiss (8 november 1916 – 10 mei 1982)

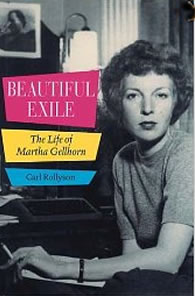

De Amerikaans schrijfster en oorlogscorrespondente Martha Ellis Gellhorn werd geboren in St. Louis, Missouri op 8 november. Martha Gellhorn was de belangrijkste vrouwelijke oorlogscorrespondent van de twintigste eeuw. Een moedige vrouw die op zoveel mogelijk fronten aanwezig wilde zijn en kritisch en sociaal bewogen schreef over de invloed van de oorlog op burgers en soldaten. Een enigszins zwart-witte politieke visie stond haar niet in de weg en zij werd wereldberoemd. Van eind jaren dertig tot in de jaren tachtig was ze actief. Van de politionele acties in Indonesië tot – in 1983 nog – de burgeroorlog in El Salvador. Pas toen de oorlog in Bosnië in 1992 uitbrak besloot ze dat ze te oud was om andermaal naar het front af te reizen. Hoogtepunten in haar carrière waren de Spaanse Burgeroorlog, de Tweede Wereldoorlog en de oorlog in Vietnam. Daarnaast bezocht ze fronten in China, het Midden-Oosten, Finland en Midden-Amerika. Gellhorn reisde met Ernest Hemingway in 1937 naar Spanje om er de burgeroorlog te verslaan. Later in 1940 trouwden ze (haar tweede, zijn derde huwelijk), maar de twee grote en ambitieuze ego’s verdroegen elkaar niet erg goed. Zij was een beter journalistiek schrijver, hij was een getalenteerd romanschrijver. Tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog verslechterde hun relatie ingrijpend, zij verliet hem en ze scheidden in 1945. Martha Gellhorn trouwde nog een derde keer, in 1954, met de hoofdredacteur van Time, T.S. Matthews. Het huwelijk duurde negen jaar. Hoewel bekend door haar carrière als oorlogsverslaggever was zij geen onverdienstelijk fictieschrijver die vijf romans, veertien novellen en twee verhalenbundels schreef.

Uit: Travels with Myself and Another

„I was seized by the idea of this book while sitting on a rotten little beach at the western tip of Crete, flanked by a waterlogged shoe and a rusted potty. Around me, the litter of our species. I had the depressed feeling that I spent my life doing this sort of thing and might well end my days here. This is the traveller’s deep dark night of the soul and can happen anywhere at any hour. No one suggested or recommended this sewer. I found it unaided, studying a map on the cheap night flight to Heraklion. Very pleased with myself too because I’d become so practical; before leaping into the unknown I actually telephoned the Greek Tourist Office in London and received a map of Crete, a list of hotels and the usual travel bumpf written in the usual purple prose. Reading matter for the plane.

Way off there, alone on a bay, was a place named Kastelli with one C Class hotel. Just the ticket; far from the beaten track, the C Class hotel was sure to be a sweet little taverna, clean, no running water, grape arbour. I pictured Kastelli as an unspoiled fishing village, sugar cube houses clustered behind a golden beach. A

ll day I would swim in lovely water, the purpose of the journey; at night I would drink ouzo in the grape arbour and watch the fishermen lollop about like Zorba under the moon.

It took as long to get from Heraklion to Kastelli, by three buses, as from London to New York by Jumbo Jet. All buses sang Arab-type Musak. Kastelli had two streets of squat cement dwellings and shops; the Aegean was not in sight. The C Class hotel was a three-storey cement box; my room was a cubby-hole with a full compliment of dead flies, mashed mosquitoes on the walls and hairy dust balls drifting around the floor. The population of Kastelli, not surprisingly, appeared sunk in speechless gloom, none more so than the proprietor of the C Class hotel where I was, also not surprisingly, the only guest. On the side of the Post Office, across from my room, a political enthusiast had painted a large black slogan. Amepikanoi was the first word, and I needed no Greek to know that it meant Yank Go Home. You bet your boots, gladly, cannot wait to oblige; but there was no way out until the afternoon bus the next day“

Martha Ellis Gellhorn (8 november 1908 – 16 februari 1998)

Met Hemingway op hun huwelijksreis in Honolulu in 1940

De Duitse schrijver Detlef Opitz werd geboren op 8 november 1956 in Steinheidel-Erlabrunn. Na zijn opleiding tot monteur werkte hij tussen 1975 en 1982 als technisch assistent in een bibliotheek, als poppenspeler, verkoper, ober en postbode in Halle. In 1980 werd hij toegelaten tot de literatuurstudie in Leipzig, maar door toedoen van de veiligheidsdienst van de DDR weer uitgesloten van de studie. Ook werd het hem onmogelijk gemaakt om te publiceren. Sinds 1982 woont Opitz in de Berlijnse wijk Prenzlauer Berg en maakt hij deel uit ban de Oost-Berlijnse literatuur- en cultuurscene. Tot 1989 publiceerde hij in „ondergrondse“ tijdschtiften als Ariadnefabrik, Entwerter Oder, Mikado, en Schaden und Verwendung.Wegens zijn betrokkenheid bij de oppositie werd hij verschillende keren gearresteerd en in 1985 wegens “gesellschaftlichen Missverhaltens” tot vier jaar verbanning uit Berlijn veroordeeld. Zijn advocaten in die tijd waren Gregor Gysi und Lothar de Maizière.

Der Büchermörder

“…nicht allein, daß der alte Kaufmann Schmidt angefallen worden war, vorne beim Marktplatz, und ausgeräubert, auch nicht allein die brachiatische Wuth, wie man ihm das Eisen über den Schädel gezogen, nein, erst der Kaltsinn des gottlosen Schurken – mög er sich zum griechischen Pi schern, der Hunt! -, erst der vornehme Anstand seines Benehmens just nach der greulichen That war es, der vor allem die Gemüther erhitzte. Noch Wochen nach dem affrösen Uiberfall, als der recht gar zu bedauernde Kaufmann endlich seinen letzten schmerzhaften Atemzug gethan im April, und seinem verschorften Kopfe dieser gräßliche Druck entwichen war, wie die Seele einem strengen Gefängniß, noch dann mochte wohl dieser oder jener fiebrigen Küchenmamsell das Zünglein in bedenckliche Ventilirung gerathen seyn, auch hätte bis in den Sommer hinein, bis die Sache sich wieder abgestillet, manch artiger Mann auf der Straße sich mit Dolchen und Äxten versehen, immer auf der Acht, daß, wenn in der Dunckelheit ihm einer begegnet, mit der langen Nase einer, dem man es sonst nie ansieht…

Auch wir, frags Gott, sind ob der kaltschnäuzigen Art noch heute und wann immer sie uns in den Sinn tritt so aufgeregt und hin- und hochgerissen, als daß es uns schwer fallen will, Euch die Geschichte ihrem natürlichen Habitus nach zu relationiren. So mag vielleicht ein Gläschen fürnher uns das Blut etwas binden und hülfreich sein, die Gedancken zu entzwirrn.

Der Kaufmann Friedrich Wilhelm Schmidt stand im 72sten Jahr seines Alters. Er wohnte drei Treppen hoch in der Grimmaischen Gasse vier, seinem eigenthümlichen Hause, grad gegenüber vom Naschmarkt. Das ist, wir wissen, liebe Fräundin, wie sehr Euch die Litteratur doch so am Herzen beliegt, das ist nur zwey Häuser entfernt von Nº 6, des erst unlängst mit Tod abgegangenen Dichters Seume letzten Quartiers. So unser Herr aber kaum mehr den Geschäften anhing und dessenstatt als Rentier ein commodes Auskommen besaß, so verließ er auch nur ungern noch sein Logis – mochten es die Tücken und Krimmen des Alters seyn, wer weiß das schon, in diesem 11/12er Winter zumal, an dessen klirrende Kälte denn auch viele sich noch erinnern mögen – bis in den März hinein lag in den Straßen fußhoch der Schnee. Das Jahr schrieb sich aber erst den 28sten Januarius in die Kalender, Diensttag, die Uhren hatten des Tages 10te Stunde geschlagen, als der Schmidtischen Hausmagd, der Concordie Marie Vetter, doch gleich so sinister zumuthe war, wie sie ihrem langwierigen Dienstherrn einen Besucher vermeldete, einen, der in Geschäften ein Unterreden begehrte und darob extra aus Hamburg herbeigereist kam.

Aus Hammaburg? sann der greise Kaufmann, selbst aus dem Norden gebürtig, und schlug

sogleich ein längst erledigtes Bordereau zu, über welchem er in schönster Erinnerung jener guten alten Tage gebeugt saß, als noch die täglichen Geschäfte seinem Leben der Quell warn. – ›Nur zu! Tritt er ein!‹ rief er darauf in Richtung Vorsaal, durchaus erfreut über den Ruf, den er wohl noch weithin besaß. ›Tritt er ein! Nur zu, der Herr! Was macht der Blanke Hanns?‹

Detlef Opitz (Steinheidel-Erlabrunn, 8 november 1956)

De Russische dichteres en schrijfster Zinaida Gippius werd geboren op 8 november 1869 in Beljov in de buurt van Tula. Gippius en haar man, de Russische filosoof Merezhkovsky waren aanhangers van de revoluties van 1905 en van 1917, maar de machtsovername door de bolsjewieken wezen zij af. Op 24 december 1919 vluchtten zij richting Polen en bleven een tijdje in Minsk en Warschau, waar ze lezingen hielden en politieke pamfletten schreven. Aanvankelijk bleef Gippius wat in de schaduw van haar man. Wel organiseerdehet echtpaar literaire salons, waarin zij snel het middelpunt van jong talent vormden. Lang leefde het echtpaar in een ménage à trois, eerst met de homosexuele publicist Dmitri Filossofov, later met de jonge dichter Wladimir Slobin. De tragedie van het leven en werken van een schrijver in ballingschap is een hoofdthema van haar werk.

Freedom

1904

I hate to submit to the people’s desire.

Who likes a yoke of a slave?

Trough whole our life we’re in permanent trial,

After – we lay in a grave.

I can’t submit to the Heavenly Low

If Lord are my love and my light.

He gave me the ways on the earth, I’ve to go,

How I can step aside?

I break all nets by which people are drawn –

Dreams, deepest sadness and bliss.

We are not slaves, we are children His own,

Children are free as He is.

I pray my God, who produced all the living,

Using the name of His Son:

Father, let our unambiguous willing

Ever be righteous and one!

Festivity

1917

The vomit of the war – the feast of the October!

From all this wine, that desperately stinks,

Oh, how loathsome was later your hangover,

My country, sunk in poverty and sins!

To please which dogs or swarms of awful demons,

To what a dream of what an evil sleep,

The people killed their freedom in their madness,

And even didn’t killed – just flogged to death by a weep?

The dogs and imps laugh o’er a fishy bone

And guns, too, laugh, through their mouths-spans …

You’ll soon be penned by sticks into your pigsty, old, —

The people, not respecting own saints.

Vertaald door Yevgeny Bonver

Zinaida Gippius (8 november 1869 – 9 september 1945)

De Ameikaanse schrijfster Margaret Mitchell werd geboren op 8 november 1900 in Atlanta, Georgia. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 november 2006.

Uit: Gone with the wind

„The next morning Scarlett’s body was so stiff and sore from the long miles of walking and jolting in the wagon that every movement was agony. Her face was crimson with sunburn and her blistered palms raw. Her tongue was furred and her throat parched as if flames had scorched it and no amount of water could assuage her thirst. Her head felt swollen and she winced even when she turned her eyes. A queasiness of the stomach reminiscent of the early days of her pregnancy made the smoking yams on the breakfast table unendurable, even to the smell. Gerald could have told her she was suffering the normal aftermath of her first experience with hard drinking but Gerald noticed nothing. He sat at the head of the table, a gray old man with absent, faded eyes fastened on the door and head cocked slightly to hear the rustle of Ellen’s petticoats, to smell the lemon verbena sachet.

As Scarlett sat down, he mumbled: “We will wait for Mrs. O’Hara. She is late.” She raised an aching head, looked at him with startled incredulity and met the pleading eyes of Mammy, who stood behind Gerald’s chair. She rose unsteadily, her hand at her throat and looked down at her father in the morning sunlight. He peered up at her vaguely and she saw that his hands were shaking, that his head trembled a little.

Until this moment she had not realized how much she had counted on Gerald to take command, to tell her what she must do, and now — Why, last night he had seemed almost himself. There had been none of his usual bluster and vitality, but at least he had told a connected story and now — now, he did not even remember Ellen was dead. The combined shock of the coming of the Yankees and her death had stunned him. She started to speak, but Mammy shook her head vehemently and raising her apron dabbed at her red eyes.

“Oh, can Pa have lost his mind?” thought Scarlett and her throbbing head felt as if it would crack with this added strain. “No, no. He’s just dazed by it all. It’s like he was sick. He’ll get over it. He must get over it. What will I do if he doesn’t? — I won’t think about it now. I won’t think of him or Mother or any of these awful things now. No, not till I can stand it. There are too many other things to think about — things that can be helped without my thinking of those I can’t help.”

She left the dining room without eating, and went out onto the back porch where she found Pork, barefooted and in the ragged remains of his best livery, sitting on the steps cracking peanuts. Her head was hammering and throbbing and the bright sunlight stabbed into her eyes. Merely holding herself erect required an effort of will power and she talked as briefly as possible, dispensing with the usual forms of courtesy her mother had always taught her to use with negroes.

Margaret Mitchell (8 november 1900 – 16 augustus 1949)

De Ierse schrijver Bram Stoker werd geboren op 8 november 1847 in Clontarf, een wijk van Dublin in Ierland. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 november 2006.

Uit: Dracula

„Jonathan Harker’s Journal 3 May. Bistritz.–Left Munich at 8:35 P.M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:46, but train was an hour late. Buda-Pesth seems a wonderful place, from the glimpse which I got of it from the train and the little I could walk through the streets. I feared to go very far from the station, as we had arrived late and would start as near the correct time as possible. The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East; the most western of splendid bridges over the Danube, which is here of noble width and depth, took us among the traditions of Turkish rule. We left in pretty good time, and came after nightfall to Klausenburgh. Here I stopped for the night at the Hotel Royale. I had for dinner, or rather supper, a chicken done up some way with red pepper, which was very good but thirsty. (Mem. get recipe for Mina.) I asked the waiter, and he said it was called “paprika hendl,” and that, as it was a national dish, I should be able to get it anywhere along the Carpathians. I found my smattering of German very useful here, indeed, I don’t know how I should be able to get on without it. Having had some time at my disposal when in London, I had visited the British Museum, and made search among the books and maps in the library regarding Transylvania; it had struck me that some foreknowledge of the country could hardly fail to have some importance in dealing with a nobleman of that country. I find that the district he named is in the extreme east of the country, just on the borders of three states, Transylvania, Moldavia, and Bukovina, in the midst of the Carpathian mountains; one of the wildest and least known portions of Europe. I was not able to light on any map or work giving the exact locality of the Castle Dracula, as there are no maps of this country as yet to compare with our own Ordance Survey Maps; but I found that Bistritz, the post town named by Count Dracula, is a fairly well-known place. I shall enter here some of my notes, as they may refresh my memory when I talk over my travels with Mina.“

Bram Stoker (8 november 1847 – 20 april 1912)