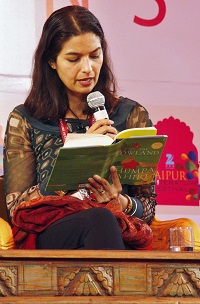

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Jhumpa Lahiri Vourvoulias werd geboren op 11 juli 1967 in Londen als dochter van Bengaalse ouders en haar de burgerlijke naam is Nilanjana Sudeshna Lahiri , maar zij kreeg de koosnaam Jhumpa. Ze groeide op in Zuid-Kingstown, Rhode Island. In 1989 studeerde ze af met een BA in Engelse literatuur aan het Barnard College; aan de Boston University, behaalde zij daarna een MA in het Engels, Creatief Schrijven en Vergelijkende Literatuurwetenschap en een Ph. D. in Renaissance studies. Aan de Boston University en de Rhode Island School of Design, gaf zij ook les in creatief schrijven. Van 1997-1998 had zij een Fellow status Provincetown’s Fine Arts Work Center. In 1999 werd haar debuut “Interpreter of Maladies“gepubliceerd. Het gaat in de collectie van negen korte verhalen over echtelijke problemen, miskraam en vervreemding onder Indiase immigranten in de VS van de eerste en tweede generatie. De verhalen spelen in het noordoosten van de Verenigde Staten en in India, vooral in Kolkata. Het boek won de Pulitzerprijs 2000 in de categorie Roman (Fictie). Haar vijfde boek “The Namesake” werd uitgebracht in 2003 en gaat over de fictieve familie Ganguli. De ouders komen allebei uit Kolkata en migreerden als jonge volwassenen naar de Verenigde Staten. Hun kinderen Gogol en Sonia groeiden er op. De uit het culturele conflict tussen ouders en kinderen voortvloeiende spanningen zijn thema van het boek. In 2007 werd het boek verfilmd. Lahiri heeft een cameo in de film. Sinds 2005 is Jhumpa Lahiri vice-voorzitter van het PEN American Center.

Uit: The Namesake

“On a sticky August evening two weeks before her due date, Ashima Ganguli stands in the kitchen of a Central Square apartment, combining Rice Krispies and Planters peanuts and chopped red onion in a bowl. She adds salt, lemon juice, thin slices of green chili pepper, wishing there were mustard oil to pour into the mix. Ashima has been consuming this concoction throughout her pregnancy, a humble approximation of the snack sold for pennies on Calcutta sidewalks and on railway platforms throughout India, spilling from newspaper cones. Even now that there is barely space inside her, it is the one thing she craves. Tasting from a cupped palm, she frowns; as usual, there’s something missing. She stares blankly at the pegboard behind the countertop where her cooking utensils hang, all slightly coated with grease. She wipes sweat from her face with the free end of her sari. Her swollen feet ache against speckled gray linoleum. Her pelvis aches from the baby’s weight. She opens a cupboard, the shelves lined with a grimy yellow-and-white-checkered paper she’s been meaning to replace, and reaches for another onion, frowning again as she pulls at its crisp magenta skin. A curious warmth floods her abdomen, followed by a tightening so severe she doubles over, gasping without sound, dropping the onion with a thud on the floor.

The sensation passes, only to be followed by a more enduring spasm of discomfort. In the bathroom she discovers, on her underpants, a solid streak of brownish blood. She calls out to her husband, Ashoke, a doctoral candidate in electrical engineering at MIT, who is studying in the bedroom. He leans over a card table; the edge of their bed, two twin mattresses pushed together under a red and purple batik spread, serves as his chair. When she calls out to Ashoke, she doesn’t say his name.

Ashima never thinks of her husband’s name when she thinks of her husband, even though she knows perfectly well what it is. She has adopted his surname but refuses, for propriety’s sake, to utter his first. It’s not the type of thing Bengali wives do. Like a kiss or caress in a Hindi movie, a husband’s name is something intimate and therefore unspoken, cleverly patched over.”

Jhumpa Lahiri (Londen, 11 juli 1967)