De Noorse schrijver Johan Harstad werd geboren op 10 februari 1979 in Stavanger. Zie ook alle tags voor Johan Harstad op dit blog.

Uit: Buzz Aldrin, What Happened to You in All the Confusion? (Vertaald door Deborah Dawkin)

„The person you love is 72,8 percent water and there’s been no rain for weeks. I’m standing out here, in the middle of the garden, my feet firmly planted on the ground. I bend over the tulips, gloves on my hands, boots on my feet, small pruning shears between my fingers, it’s extremely early, one April morning in 1999 and it’s beginning to grow warmer, I’ve noticed it recently, a certain something has begun to stir, I noticed it as I got out of the car this morning, in the gray light, as Iopened the gates into the nursery, the air had grown softer, more rounded at the edges, I’d even considered changing out of my winterboots and putting my sneakers on. I stand here in the nursery garden,by the flowers so laboriously planted and grown side by side in their beds, in their boxes, the entire earth seeming to lift, billowing green,and I tilt my head upward, there’s been sunshine in the last few days, a high sun pouring down, but clouds have moved in from the North Sea somewhere now, Sellafield radiation clouds, and in short intervals the sun vanishes, for seconds at first, until eventually more and more time passes before the sunlight is allowed through the cumulus clouds again.I lean my head back, face turned up, eyes squinting, with the sun being so strong as it forces its way through the layers of cloud. I wait.Stand and wait. And then I see it, somewhere up there, a thousand, perhaps three thousand feet above, the first drop takes shape and falls, releases hold, hurtles toward me, and I stand there, face turned up, it’s about to start raining, in a few seconds it will pour, and never stop, at least that’s how it will seem, as though a balloon had finally burst, and I stare up, a single drop on its way down toward me,heading straight, its pace increases and the water is forced to change shape with the speed, the first drop falls and there I stand motionless, until I feel it hit me in the center of my forehead, exploding outward and splitting into fragments that land on my jacket, on the flowers beneath me, my boots, my gardening gloves. I bow my head. And it begins to rain.”

Johan Harstad (Stavanger, 10 februari 1979)

De Noorse schrijfster en journaliste Åsne Seierstad werd geboren in Oslo op 10 februari 1970. Zie ook alle tags voor Åsne Seierstad op dit blog.

Uit: The Bookseller of Kabul (Vertaald door Ingrid Christophersen)

“A friend of mine would like to marry Sonya,” he told the parents.

It was not the first time someone had asked for their daughter’s hand. She was beautiful and diligent, but they thought she was still a bit young. Sonya’s father was no longer able to work. During a brawl a knife had severed some of the nerves in his back. His beautiful daughter could be used as a bargaining chip in the marriage stakes, and he and his wife were always expecting the next bid to be even higher.

“He is rich,” said Sultan. “He’s in the same business as I am. He is well educated and has three sons. But his wife is starting to grow old.”

“What’s the state of his teeth?” the parents asked immediately, alluding to the friend’s age.

“About like mine,” said Sultan. “You be the judge.”

Old, the parents thought. But that was not necessarily a disadvantage. The older the man, the higher the price for their daughter. A bride’s price is calculated according to age, beauty, and skill and according to the status of the family.

When Sultan Khan had delivered his message, the parents said, as could be expected, “She is too young.”

Anything else would be to sell short to this rich, unknown suitor whom Sultan recommended so warmly. It would not do to appear too eager. But they knew Sultan would return; Sonya was young and beautiful.

He returned the next day and repeated the proposal. The same conversation, the same answers. But this time he got to meet Sonya, whom he had not seen since she was a young girl.”

Åsne Seierstad (Oslo, 10 februari 1970)

De Duitse schrijfster Simone Trieder werd geboren op 10 februari 1959 in Quedlinburg. Zie ook alle tags voor Simone Trieder op dit blog.

Uit: Im Prinzip lieb

“Graf drückte, friedlich gestimmt, auf die Taste mit der Lucky-Strike-Marke.

Iv saß schon im Auto und hörte aufmerksam Nachrichten. „Also denn“, sagte sie. Es ging zu Vivian, die ihre Mutter zu einem Abrisshaus bestellt hatte. Felix war im Spätdienst, deshalb hatte Iv Graf gebeten mitzukommen. Im Kofferraum lag eine monströse Ziehharmonika-Liege, nach der Vivian verlangte. „Die steht doch sowieso nur bei euch im Schuppen rum.“

„Wir kriegen sie am Wohlstandshaken“, hatte Iv gesagt. „Sie ist ein verwöhntes Einzelkind, das verzichtet doch nicht auf das, was ihr das Leben ganz automatisch anbietet.“

„Sie revoltiert, das ist ganz normal, dass ein Kind in ihrem Alter gegen die Eltern revoltiert“, sagte Graf.

„Weil wir so schreckliche Eltern sind“, Iv gab Gas. „Und was ist mit deinen Kindern, weißt du, ob sie nicht gerade auf der Straße leben und sich fragen, wo ihr Vater ist?“

Graf sah geradeaus. „Ich weiß es nicht.“

Simone Trieder (Quedlinburg, 10 februari 1959)

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Bertolt Brecht werd op 10 februari 1898 in de Zuid-Duitse stad Augsburg geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Bertolt Brecht op dit blog.

Uit: Das Leben des Galilei

“Galilei akademisch, die Hände über dem Bauch gefaltet: In meinen freien Stunden, deren ich viele habe, bin ich meinen Fall durchgegangen und habe darüber nachgedacht, wie die Welt der Wissenschaft, zu der ich mich selber nicht mehr zähle, ihn zu beurteilen haben wird. (…)

Der Verfolg der Wissenschaft scheint mir diesbezüglich besondere Tapferkeit zu erheischen. Sie handelt mit Wissen, gewonnen durch Zweifel. Wissen verschaffend über alles für alle, trachtet sie, Zweifler zu machen aus allen. Nun wird der Großteil der Bevölkerung von ihren Fürsten, Grundbesitzern und Geistlichen in einem perlmutternen Dunst von Aberglauben und alten Wörtern gehalten, welcher die Machinationen3 dieser Leute verdeckt. (…) Diese selbstischen und gewalttätigen Männer, die sich die Früchte der Wissenschaft gierig zunutze gemacht haben, fühlten zugleich das kalte Auge der Wissenschaft auf ein tausendjähriges, aber künstliches Elend gerichtet, das deutlich beseitigt werden konnte, indem sie beseitigt wurden. Sie überschütteten uns mit Drohungen und Bestechungen, unwiderstehlich für schwache Seelen. Aber können wir uns der Menge verweigern und doch Wissenschaftler bleiben? (…) Wofür arbeitet ihr? Ich halte dafür, daß das einzige Ziel der Wissenschaft darin besteht, die Mühseligkeit der menschlichen Existenz zu erleichtern. Wenn Wissenschaftler, eingeschüchtert durch selbstsüchtige Machthaber, sich damit begnügen, Wissen um des Wissens willen aufzuhäufen, kann die Wissenschaft zum Krüppel gemacht werden, und eure neuen Maschinen mögen nur neue Drangsale bedeuten.”

Bertolt Brecht (10 februari 1898 – 14 augustus 1956)

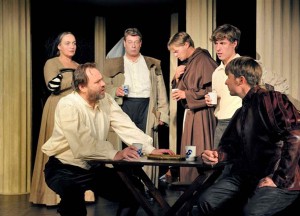

Scene uit “Das Leben des Galilei,” Landesbühne Rheinland-Pfalz, 2010

De Russische dichter en schrijver Boris Leonidovich Pasternak werd geboren in Moskou op 10 februari 1890. Zie ook alle tags voor Boris Pasternak op dit blog.

A Dream

I dreamt of autumn in the window’s twilight,

And you, a tipsy jesters’ throng amidst. ‘

And like a falcon, having stooped to slaughter,

My heart returned to settle on your wrist.

But time went on, grew old and deaf. Like thawing

Soft ice old silk decayed on easy chairs.

A bloated sunset from the garden painted

The glass with bloody red September tears.

But time grew old and deaf. And you, the loud one,

Quite suddenly were still. This broke a spell.

The dreaming ceased at once, as though in answer

To an abruptly silenced bell.

And I awakened. Dismal as the autumn

The dawn was dark. A stronger wind arose

To chase the racing birchtrees on the skyline,

As from a running cart the streams of straws.

March

The sun is hotter than the top ledge in a steam bath;

The ravine, crazed, is rampaging below.

Spring — that corn-fed, husky milkmaid —

Is busy at her chores with never a letup.

The snow is wasting (pernicious anemia —

See those branching veinlets of impotent blue?)

Yet in the cowbarn life is burbling, steaming,

And the tines of pitchforks simply glow with health.

These days — these days, and these nights also!

With eavesdrop thrumming its tattoos at noon,

With icicles (cachectic!) hanging on to gables,

And with the chattering of rills that never sleep!

All doors are flung open — in stable and in cowbarn;

Pigeons peck at oats fallen in the snow;

And the culprit of all this and its life-begetter–

The pile of manure — is pungent with ozone.

Boris Pasternak (10 februari 1890 – 30 mei 1960)

De Joods-Oostenrijks-Britse schrijver Jakov Lind (pseudoniem van Heinz Landwirth) werd geboren in Wenen op 10 februari 1927. Zie ook alle tags voor Jakov Lind dit blog.

Uit: Ergo (Vertaald door Ralph Manheim)

“Slowly and heavily, a hippopotamus rising from the Nile, he rose from the paper mountain, beat the nightmare of virginal lewdness out of his clothes and stood there, a squat man of sixty with short gray hair and swollen lips, crossing his hands over his forehead, and looked around him darkly. Have you been watching me again while I was asleep? Have you been spying on me, you scum? You’re living by my sufferance, remember that. Tomorrow it will be all up with you. I’ll throw you both out. Both of you.

What time is it?

Nine o’clock, Father. Aslan called him Father because of the difference in their ages and in token of devotion and gratitude. Nine o’clock, eh? Wacholder was now able to shout, so he shouted.

Yes, nine o’clock, Father.

What about my tea?

Leo jumped out of bed again (has he gone plumb crazy?) and picked at his molar with satisfaction as Aslan obediently brought down his own tea. Aslan can do what he likes, I’m here to work.

Wacholder warmed his hands on the lukewarm tea. They’ve been here again, Aslan, the big black ones, do you hear. They’ve visited me again, Aslan, as big as gothic letters, up and down the wall of my heart, Aslan, up and down, and the Latin letters too, as green and thick as creepers. A whole bellyful, Aslan, it turned my stomach, Aslan.

And then the rats, as big as big steamships, back and forth, back and forth. What do you think, Aslan, should I call the doctor?

Call the doctor, Father.

No, I won’t call the doctor. I’ve changed my mind. Let them crawl, let them bob up and down, let them gnaw and creep and root about. Let them hollow me out. Man is a pipe.

Yes, Father.”

Jakov Lind (10 februari 1927 – 17 februari 2007)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 10e februari ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag en eveneens mijn eerste blog van vandaag.