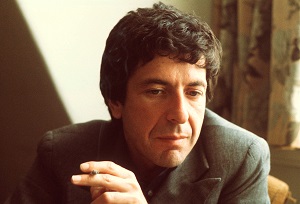

De Canadese dichter, folk singer-songwriter en schrijver Leonard Cohen werd geboren op 21 september 1934 te Montréal. Zie ook alle tags voor Leonard Cohen op dit blog.

Uit: The favorite game

“Breavman knows a girl named Shell whose ears were pierced so she could wear the long filigree earrings. The punctures festered and now she has a tiny scar in each earlobe. He discovered them behind her hair. A bullet broke into the flesh of his father’s arm as he rose out of a trench. It comforts a man with coronary thrombosis to bear a wound taken in combat. On the right temple Breavman has a scar which Krantz bestowed with a shovel. Trouble over a snowman. Krantz wanted to use clinkers as eyes. Breavman was and still is against the use of foreign materials in the decoration of snowmen. No woollen muf-flers, hats, spectacles. In the same vein he does not approve of inserting carrots in the mouths of carved pumpkins or pinning on cucumber ears.

His mother regarded her whole body as a scar grown over some earlier perfection which she sought in mirrors and windows and hub-caps. Children show scars like medals. Lovers use them as secrets to reveal. A scar is what happens when the word is made flesh. It is easy to display a wound, the proud scars of combat. It is hard to show a pimple.

Breavman’s young mother hunted wrinkles with two hands and a magnifying mirror. When she found one she consulted a fortress of oils and creams arrayed on a glass tray and she sighed. Without faith the wrinkle was anointed. “This isn’t my face, not my real face.” “Where is your real face, Mother?” “Look at me. Is this what I look like?” “Where is it, where’s your real face?” “I don’t know, in Russia, when I was a girl.” He pulled the huge atlas out of the shelf and fell with it. He sifted pages like a goldminer until he found it, the whole of Russia, pale and vast. He kneeled over the distances until his eyes blurred and he made the lakes and rivers and names become an incredible face, dim and beautiful and easily lost. The maid had to drag him to supper.”

Leonard Cohen (21 september 1934 – 7 november 2016)

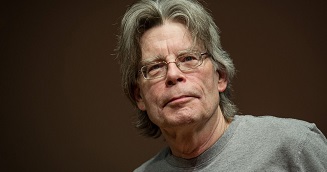

De Amerikaanse schrijver Stephen Edwin King werd geboren in Portland, Maine, op 21 september 1947. Zie ook alle tags voor Stephen King op dit blog.

Uit: Finders Keepers

“Wake up, genius.”

Rothstein didn’t want to wake up. The dream was too good. It featured his first wife months before she became his first wife, seventeen and perfect from head to toe. Naked and shimmering. Both of them naked. He was nineteen, with grease under his fingernails, but she hadn’t minded that, at least not then, because his head was full of dreams and that was what she cared about. She believed in the dreams even more than he did, and she was right to believe. In this dream she was laughing and reaching for the part of him that was easiest to grab. He tried to go deeper, but then a hand began shaking his shoulder, and the dream popped like a soap bubble.

He was no longer nineteen and living in a two-room New Jersey apartment, he was six months shy of his eightieth birthday and living on a farm in New Hampshire, where his will specified he should be buried. There were men in his bedroom. They were wearing ski masks, one red, one blue, and one canary-yellow. He saw this and tried to believe it was just another dream—the sweet one had slid into a nightmare, as they sometimes did—but then the hand let go of his arm, grabbed his shoulder, and tumbled him onto the floor. He struck his head and cried out.

“Quit that,” said the one in the yellow mask. “You want to knock him unconscious?”

“Check it out.” The one in the red mask pointed. “Old fella’s got a woody. Must have been having one hell of a dream.”

Blue Mask, the one who had done the shaking, said, “Just a piss hard-on. When they’re that age, nothing else gets em up. My grandfather—”

“Be quiet,” Yellow Mask said. “Nobody cares about your grandfather.”

Although dazed and still wrapped in a fraying curtain of sleep, Rothstein knew he was in trouble here. Two words surfaced in his mind: home invasion. He looked up at the trio that had materialized in his bedroom, his old head aching (there was going to be a huge bruise on the right side, thanks to the blood thinners he took), his heart with its perilously thin walls banging against the left side of his ribcage. They loomed over him, three men with gloves on their hands, wearing plaid fall jackets below those terrifying balaclavas. Home invaders, and here he was, five miles from town.”

Stephen King (Portland, 21 september 1947)

De Franse schrijver Frédéric Beigbeder werd geboren op 21 september 1965 in Neuilly-sur-Seine. Zie ook alle tags voor Frédéric Beigbeder op dit blog.

Uit: Un roman français

« Je ne me souviens pas de mon enfance. Quand je le dis, personne ne me croit. Tout le monde se souvient de son passé; à quoi bon vivre si la vie est oubliée? En moi rien ne reste de moi-même; de zéro à quinze ans je suis face à un trou noir (au sens astrophysique: «Objet massif dont le champ gravitationnel est si intense qu’il empêche toute forme de matière ou de rayonnement de s’en échapper»). Longtemps j’ai cru que j’étais normal, que les autres étaient frappés de la même amnésie. Mais si je leur demandais: «Tu te souviens de ton enfance?», ils me racontaient quantité d’histoires. J’ai honte que ma biographie soit imprimée à l’encre sympathique. Pourquoi mon enfance n’est-elle pas indélébile? Je me sens exclu du monde, car le monde a une archéologie et moi pas. J’ai effacé mes traces comme un criminel en cavale. Quand j’évoque cette infirmité, mes parents lèvent les yeux au ciel, ma famille proteste, mes amis d’enfance se vexent, d’anciennes fiancées sont tentées de produire des documents photographiques.

Je ne mens pas par omission: je fouille dans ma vie comme dans une malle vide, sans y rien trouver; je suis désert. Parfois j’entends murmurer dans mon dos: «Celui-là, je n’arrive pas à le cerner.» J’acquiesce. Comment voulezvous situer quelqu’un qui ignore d’où il vient? Comme dit Gide dans Les Faux-Monnayeurs, je suis «bâti sur pilotis: ni fondation, ni soussol». La terre se dérobe sous mes pieds, je lévite sur coussin d’air, je suis une bouteille qui flotte sur la mer, un mobile de Calder. Pour plaire, j’ai renoncé à avoir une colonne vertébrale, j’ai voulu me fondre dans le décor tel Zelig, l’homme-caméléon. Oublier sa personnalité, perdre la mémoire pour être aimé: devenir, pour séduire, celui que les autres choisissent. Ce désordre de la personnalité, en langage psychiatrique, est nommé «déficit de conscience centrée». Je suis une forme vide, une vie sans fond. Dans ma chambre d’enfant, rue Monsieur-le-Prince, j’avais punaisé, m’a-t-on dit, une affiche de film sur le mur: Mon Nom est Personne. Sans doute m’identifiais-je au héros.”.

Frédéric Beigbeder (Neuilly-sur-Seine, 21 september 1965)

De Vlaamse dichter Xavier Roelens werd op 21 september 1976 in Rekkem (Menen) geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Xavier Roelens op dit blog.

Onze partner wandelt terug

van elke reis brengt hij voor vrouw en dochter storm en stenen mee.

hij kauwt ter voorbereiding kiezels:

‘De kwolste kwt kwiewelt awn hwar gwt’ (13x)

kijkt uit voor een paal of kortgerokt meisje

om tegenaan te lopen.

in zijn onoplettendheid durft hij

in retorische vragen te trappen en lokken

echo’s uit de keuken geen lawines uit?

onder het puin

bekijkt hij foto’s in zijn lonely planet

en bidt een reddingsteam.

Nota aan onze partner

bij overstromingen mag onze partner op een koe klimmen.

wat voorbijdrijft

Onderrug Onderrug Onderrug Onderrug

vraagt om de competentie

het niet aan te raken

er is watertekort bij overstromingen.

overstromingen maken onze partner flexibel in onwetendheid.

het vuur in een naburige stad is niet schadelijk

van kilometers ver fucking Onderrug

voor de gezondheid

Xavier Roelens (Rekkem, 21 september 1976)

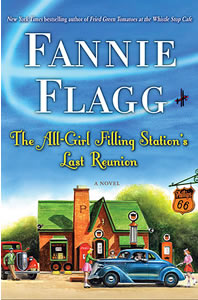

De Amerikaanse schrijfster en actrice Fannie Flagg (eig. Patricia Neal) werd geboren op 21 september in Birmingham (Alabama). Zie ook alle tags voor Fannie Flagg op dit blog.

Uit: The All-Girl Filling Station’s Last Reunion

„Mrs. Earle Poole, jr., better known to mends and family as Sookie, was driving home from the Birds-R-Us store out on Highway 98 with one ten-pound bag of sunflower seeds and one ten-pound bag of wild bird seed and not her usual weekly purchase for the past fikeen years of one twenty-pound bag of the Pretty Boy Wild Bird Seed and Sunflower Mix. As she had explained to Mr. Nadleshaft, she was wor-ried that the smaller birds were still not getting enough to eat. Every morning lately, the minute she filled her feeders, the larger, more ag-gressive blue jays would swoop in and scare the little bids all away. She noticed that the blue jays always ate the sunflower seeds first, and so tomorrow, she was going to try putting just plain sunflower seeds in her backyard feeders, and while the blue jays were busy eating them, she would run around the house as fast as she could and put the wild bird seed in the feeders in the front yard. That way, her poor finches and titmice might be able to get a little something, at least.

As SHE DROVE OVER the Mobile Bay Bridge, she looked out at the big white puffy clouds and saw a long row of pelicans flying low over the water. The bay was sparkling in the bright sun and already dotted with red, white, and blue sailboats headed out for the day. A few people fishing alongside the bridge waved as she passed by, and she smiled and waved back. She was almost to the other side when she suddenly began to experience some sort of a vague and unusual sense of well-being. And with good reason. Against all odds, she had just survived the last wedding of their three daughters, Dee Dec, Cc Ce, and Le Le. Their only unmarried child now was their twenty-five-year-old son, Carter, who lived in Atlanta. And some other poor (God help her), beleaguered mother of the bride would be in charge of planning that happy occasion.”

Fannie Flagg (Birmingham, 21 september 1944)

Cover

De Britse schrijver Herbert George Wells werd geboren op 21 september 1866 in Bromley, Kent. Zie ook alle tags voor H. G. Wells op dit blog.

Uit: Tales of Space and Time (The Chrystal Egg)

“There was, until a year ago, a little and very grimy-looking shop near Seven Dials, over which, in weather-worn yellow lettering, the name of “C. Cave, Naturalist and Dealer in Antiquities,” was inscribed. The contents of its window were curiously variegated. They comprised some elephant tusks and an imperfect set of chessmen, beads and weapons, a box of eyes, two skulls of tigers and one human, several moth-eaten stuffed monkeys (one holding a lamp), an old-fashioned cabinet, a flyblown ostrich egg or so, some fishing-tackle, and an extraordinarily dirty, empty glass fish-tank. There was also, at the moment the story begins, a mass of crystal, worked into the shape of an egg and brilliantly polished. And at that two people, who stood outside the window, were looking, one of them a tall, thin clergyman, the other a black-bearded young man of dusky complexion and unobtrusive costume. The dusky young man spoke with eager gesticulation, and seemed anxious for his companion to purchase the article.

While they were there, Mr. Cave came into his shop, his beard still wagging with the bread and butter of his tea. When he saw these men and the object of their regard, his countenance fell. He glanced guiltily over his shoulder, and softly shut the door. He was a little old man, with pale face and peculiar watery blue eyes; his hair was a dirty grey, and he wore a shabby blue frock coat, an ancient silk hat, and carpet slippers very much down at heel. He remained watching the two men as they talked. The clergyman went deep into his trouser pocket, examined a handful of money, and showed his teeth in an agreeable smile. Mr. Cave seemed still more depressed when they came into the shop.

The clergyman, without any ceremony, asked the price of the crystal egg.

Mr. Cave glanced nervously towards the door leading into the parlour, and said five pounds. The clergyman protested that the price was high, to his companion as well as to Mr. Cave–it was, indeed, very much more than Mr. Cave had intended to ask, when he had stocked the article—and an attempt at bargaining ensued. Mr. Cave stepped to the shop-door, and held it open. “Five pounds is my price,” he said, as though he wished to save himself the trouble of unprofitable discussion. As he did so, the upper portion of a woman’s face appeared above the blind in the glass upper panel of the door leading into the parlour, and stared curiously at the two customers. “Five pounds is my price,” said Mr. Cave, with a quiver in his voice.”

H. G. Wells (21 september 1866 – 13 augustus 1946)

In 1901

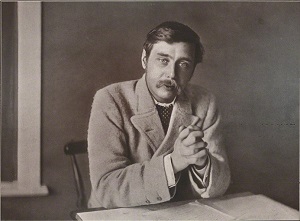

De Duitse dichter Johann Peter Eckermann werd geboren op 21 september 1792 in Winsen (Luhe). Hij was bovenal de medewerker en vriend van Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.Zie ook alle tags voor Johann Peter Eckermann op dit blog.

Uit:Gespräche mit Goethe

„Durch die offene Tür gegenüber blickte man sodann in ein ferneres Zimmer, gleichfalls mit Gemälden verziert, durch welches der Bediente gegangen war mich zu melden.

Es währte nicht lange.. so kam Goethe, in einem blauen Oberrock und in Schuhen; eine erhabene Gestalt! Der Eindruck war überraschend. Doch verscheuchte er sogleich jede Befangenheit durch die freundlichsten Worte. Wir setzten uns auf das Sofa. Ich war glücklich verwirrt in seinem Anblick und seiner Nähe, ich wußte ihm wenig oder nichts zu sagen.

Er fing sogleich an von meinem Manuskript zu reden. »Ich komme eben von Ihnen her,« sagte er; »ich habe den ganzen Morgen in Ihrer Schrift gelesen; sie bedarf keiner Empfehlung, sie empfiehlt sich selber.« Er lobte darauf die Klarheit der Darstellung und den Fluß der Gedanken, und daß alles auf gutem Fundament ruhe und wohl durchdacht sei. »Ich will es schnell befördern,« fügte er hinzu; »heute noch schreibe ich an Cotta mit der reitenden Post, und morgen schicke ich das Paket mit der fahrenden nach.«

Ich dankte ihm dafür mit Worten und Blicken.

Wir sprachen darauf über meine fernere Reise. Ich sagte ihm, daß mein eigentliches Ziel die Rheingegend sei, wo ich an einem passenden Ort zu verweilen und etwas Neues zu schreiben gedenke. Zunächst jedoch wolle ich von hier nach Jena gehen, um dort die Antwort des Herrn von Cotta zu erwarten.

Goethe fragte mich, ob ich in Jena schon Bekannte habe; ich erwiderte, daß ich mit Herrn von Knebel in Berührung zu kommen hoffe, worauf er versprach, mir einen Brief mitzugeben, damit ich einer desto bessern Aufnahme gewiß sei.

»Nun, nun!« sagte er dann, »wenn Sie in Jena sind, so sind wir ja nahe beieinander und können zueinander und können uns schreiben, wenn etwas vorfällt.«

Wir saßen lange beisammen, in ruhiger liebevoller Stimmung. Ich drückte seine Kniee, ich vergaß das Reden über seinem Anblick, ich konnte mich an ihm nicht satt sehen. Das Gesicht so kräftig und braun und voller Falten, und jede Falte voller Ausdruck. Und in allem solche Biederkeit und Festigkeit, und solche Ruhe und Größe! Er sprach langsam und bequem, so wie man sich wohl einen bejahrten Monarchen denkt, wenn er redet. Man sah ihm an, daß er in sich selber ruhet und über Lob und Tadel erhaben ist. Es war mir bei ihm unbeschreiblich wohl; ich fühlte mich beruhigt, so wie es jemandem sein mag, der nach vieler Mühe und langem Hoffen endlich seine liebsten Wünsche befriedigt sieht.“

Johann Peter Eckermann (21 september 1792 – 3 december 1854)

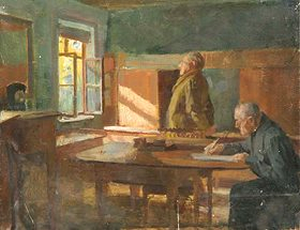

Goethe en Eckermann door Otto Rasch, ca. 1920

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata

De Engelse schrijver Max Porter werd geboren in High Wycombe in 1981. Porter studeerde kunstgeschiedenis aan Courtauld in Londen en werkte jarenlang als zelfstandige boekhandelaar, wat hem de Young Bookseller of the Year Award opleverde. Sinds 2012 is hij lector bij Granta Books. Hij debuteerde in 2015 met “Grief Is the Thing with Feathers”.

Uit: Grief Is the Thing with Feathers

“Four or five days after she died, I sat alone in the living room wondering what to do. Shufing around, waiting for shock to give way, waiting for any kind of structured feeling to emerge from the organisational fakery of my days. I felt hung-empty. The children were asleep. I drank. I smoked roll-ups out of the window. I felt that perhaps the main result of her being gone would be that I would permanently become this organiser, this list-making trader in clichés of gratitude, machine-like architect of routines for small children with no Mum. Grief felt fourth-dimensional, abstract, faintly familiar. I was cold.

The friends and family who had been hanging around being kind had gone home to their own lives. When the children went to bed the flat had no meaning, nothing moved.

The doorbell rang and I braced myself for more kindness. Another lasagne, some books, a cuddle, some little potted ready-meals for the boys. Of course, I was becoming expert in the behaviour of orbiting grievers. Being at the epicentre grants a curiously anthropological awareness of everybody else; the overwhelmeds, the affectedly lackadaisicals, the nothing so fars, the overstayers, the new best friends of hers, of mine, of the boys. The people I still have no fucking idea who they were. I felt like Earth in that extraordinary picture of the planet surrounded by a thick belt of space junk. I felt it would be years before the knotted-string dream of other people’s performances of woe for my dead wife would thin enough for me to see any black space again, and of course – needless to say – thoughts of this kind made me feel guilty. But, I thought, in support of myself, everything has changed, and she is gone and I can think what I like. She would approve, because we were always over-analytical, cynical, probably disloyal, puzzled. Dinner party post-mortem bitches with kind intentions. Hypocrites. Friends.

The bell rang again.

I climbed down the carpeted stairs into the chilly hallway and opened the front door.

There were no streetlights, bins or paving stones. No shape or light, no form at all, just a stench.

There was a crack and a whoosh and I was smacked back, winded, onto the doorstep. The hallway was pitch black and freezing cold and I thought, ‘What kind of world is it that I would be robbed in my home tonight?’ And then I thought, ‘Frankly, what does it matter?’ I thought, ‘Please don’t wake the boys, they need their sleep. I will give you every penny I own just as long as you don’t wake the boys.”

Max Porter (High Wycombe, 1981)

De Nieuw-Zeelandse schrijver Paul Ewen werd geboren in Blenheim, Nieuw Zeeland in 1972. In 1995 verhuisde hij naar Azië waar hij zes jaar woonde, waaronder vier jaar in Saigon. Tegenwoordig woont hij in het zuiden van Londen. In Nieuw Zeeland werd zijn werk gepubliceerd in Landfall and Sport en in het Verenigd Koninkrijk zijn verhalen verschenen in de British Council’s New Writing Anthology (bewerkt door Ali Smith en Toby Litt), en ook in het Times Higher Education Supplement en Tank Magazine. Hij heeft geschreven voor Dazed & Confused, en is een vaste medewerker aan Hamish Hamilton’s online magazine Five Dials. Zijn eerste boek “London Pub Reviews” (2007) werd een kruising tussen Blade Runner en Coronation Street genoemd en ‘een werk van een komisch genie. In 2014 verscheen “Francis Plug: How To Be A Public Author”, het boek waarmee hij bij een groter publiek bekend werd.

Uit:Francis Plug – How To Be A Public Author

“The water in Salman Rushdie’s glass is rippling. The glass itself is perfectly still, sitting flat on the even table surface, but the water inside is rippling. It’s Still water, but it’s rippling. I know it’s Still water because I can read the label on the bottle. Still Spring Water. I’m sitting in the front row. I can see it with my own eyes.

Salman Rushdie has barely touched his water, unsurprisingly. The water was placed on the table shortly before 18:30, and he didn’t sit down until 19:07. So it’s been sitting there, warming, for nearly forty minutes. Imagine what it must taste like now, especially under all those bright lights. Like a heated swimming pool, or a glass of hot-water bottle water. Sometimes I drink the warm water in the shower when I’m washing my face, but I don’t swallow it because the taste is like something from an ornamental frog in a garden pond on a very hot day. So instead, I spit the water out down my tummy. And then I give my tummy a good soap down.

Bacteria thrives in warm water. It’s rampant in waterbeds. I heard of a couple who never cleaned their waterbed, not once. You’re supposed to add chemicals to keep the heated water free from bugs. But this couple didn’t. Perhaps they didn’t know they needed to, or maybe they just forgot. Anyway, one day they were preparing to move house, and they emptied the contents of the waterbed bladder into their bath. The water that began to sludge out of the valve was filled with dozens of little scaly things with legs and no eyes. Little hairy mites, kicking about in their clean white tub. The couple were horrified. But there was more to come. A squelching noise was heard, and out slid a huge slimy worm, two metres in length, maybe more, thicker than your thumb. They’d been sleeping on that. Sleeping on a bed of worm.

So don’t drink the complimentary water at your author events, because you might get worms.

There are other dangers too. Perhaps your unattended water bottle in the empty auditorium has been tampered with. We only have to look at the lessons learned from Agatha Christie. People in her books are forever being poisoned.She even spells out what the poison is and how it’s administered. In their drinks. The organisers of this event must be only too aware of Agatha Christie’s back catalogue, and of the brugmansia flower, formerly known as the datura, a South American pendant-shaped plant belonging to the Solanaceae family, also famed for its spicy night scent, which is used by Amazonian tribes as distilled poison to tip their arrows. It doesn’t take an idiot to work this out.”

Paul Ewen (Blenheim, 1972)