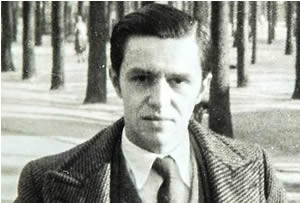

De Duitse zanger, dichter en schrijver Wolf Biermann werd geboren op 15 november 1936 in Hamburg. Zie ook alle tags voor Wolf Biermann op dit blog.

Das 66. Sonett

Müd müd von all dem schrei ich nach dem Schlaf im Tod

Weil ich ja seh: Verdienst geht betteln hier im Staat

Seh Nichtigkeit getrimmt auf Frohsinn in der Not

Und reinster Glaube landet elend im Verrat

Und Ehre ist ein goldnes Wort, das nichts mehr gilt

Und einer Jungfrau Tugend wird verkauft wie’n Schwein

Und weil Vollkommenheit man einen Krüppel schilt

Und weil die Kraft dahinkriecht auf dem Humpelbein

Gelehrte Narrn bestimmen, was als Weisheit gilt

Und Kunst seh ich geknebelt von der Obrigkeit

Und simple Wahrheit, die man simpel Einfalt schilt

Und Güte, die in Ketten unterm Stiefel schreit

Von all dem müde, wär ich lieber tot, ließ ich

In dieser Welt dabei mein Liebchen nicht im Stich

Wolkenbilder über Hamburg

Die Wolken wildern weiß im Blau

Der Wind schiebt Bilder durch die Himmel

Der Wind malt mir ‘ne Monsterschau

ein nazigrüner Kohlenklau

ein Wolf im Schafgewimmel

Ein Phönix federwölket zart

schon fingert Licht durch die Kulissen

groß bellt ein Gott mir Zickenbart

ein Hundekopf auf blauer Fahrt

hat mir mein Herz zerbissen

Wenn bloß kein Regen runterfällt,

kein kein kernkraftwerkekranker Regen

der Tod fährt lustig um die Welt

im Wolkenschiff am Himmelszelt

und wirft in Hamburg Anker

Und weißt Du was, auf einmal sah

ich oben in den Wolkenfratzen

Dein liebes Bild so schrecklich klar

Dann weinte ich, ich weiß es ja

kein Tod kann mich noch kratzen.

Wolf Biermann (Hamburg, 15 november 1936)

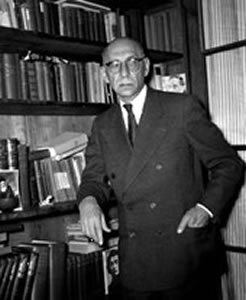

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Gerhart Hauptmann werd geboren in Obersalzbrunn (Neder-Silezië) op 15 november 1862. Zie ook alle tags voor Gerhart Hauptmann op dit blog.

Uit: Before Daybreak (Vor Sonnenaufgang)

“MRS. KRAUSE appears, dreadfully overdressed. Lost of shiny silk and expensive jewelry. Both bearing and garb betray callous arrogance, absurd vanity, and the pride born of stupidity.

HOFFMANN. Ah, there you are, Mother! Permit me to introduce my friend, Dr. Loth.

MRS. KRAUSE. (Improvises a grotesque curtsey.) Pleased-t’meetcha. (After a short pause.) Now first, Doctor, I gotta ask ya not to have no hard feelin’s toward me, ’n I’m properly sorry, so ‘scuse me, will ya? – ‘Scuse me on account o’ the way I acted afore. (The longer she speaks, the faster she speaks.) Y’know, y’unnerstan’, we got a whoppin’ big bunch o’ bums comes bummin’ their way in ’n outa these parts. … Ya wouldn’ believe the kind o’ trouble we got with them moochers. Bunch o’ magpies’ll swipe anythin’ ain’t nailed down. An’ it ain’t ‘zackly ’s if we was tight, ya know. A penny one way or t’other don’t mean nothin’ to us . . . or a Mark neither. Not on yer life! Now, you take Ludwig Krause’s ol’ lady, she’s ’s cheap ’s they come; wouldn’ give ya th’ time o’ day. Her ol’ man dropped dead in a fit o’ rage ‘cause he lost a lousy two thousan’ playin’ cards. Well, we ain’t that sort, ya know. See that buffet over there? Set me back two hunnert – ’n that don’t even include the shippin’ costs. Baron Klinkow himself ain’t got nothin’ better.

MRS. SPILLER has also entered, shortly after Mrs. Krause. She is small, somewhat deformed, and decked out in Mrs. Krause’s hand-me-downs. While Mrs. Krause speaks, she looks up at her with a kind of admiration. She is about fifty-five. Her breath is accompanied by a quiet little moan when she exhales; it is regularly audible, even when she speaks, as a soft “nnngg.”

MRS. SPILLER. (In an obsequious, affectedly melancholic, minor-key tone. Very softly.) His Lordship the Baron has the exact same buffet – nnngg – .

HELEN. (To Mrs. Krause.) Mother, don’t you think we should sit down before we . . .

MRS. KRAUSE. (With a lightning fast turn to Helen, and a scathing look; brusquely and imperiously.) Izzat fittin’ ’n proper? (She is just about to sit down when she remembers that grace has not been said. Mechanically she folds her hands without, however, managing to suppress her meanness.)

MRS. SPILLER. (Intoning.) Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest. May thy bounty to us be blessed. A-men. They take their seats noisily. With all the passing and taking of the many dishes, which occupies no mean amount of time, they manage to get over the awkwardness of the previous interchange.

HOFFMANN. (To Loth.) Help yourself, Alfred. How about some oysters?

LOTH. I’ll give them a try. First time for me.

MRS. KRAUSE. (Who has just slurped one down noisily and speaks with freshly restuffed mouth.) Ya mean this season?

LOTH. I mean ever. Mrs. Krause and Mrs. Spiller exchange glances.

HOFFMANN. (To Kahl, who is squeezing the juice from a lemon with his teeth.) Haven’t seen you for two days, Mr. Kahl. Been busy shooting up the fieldmice?

KAHL. Aw, g-g-go on.

HOFFMANN. (To Loth.) You see, Mr. Kahl is passionately devoted to hunting.

KAHL. F-f-fieldmice is inf-f-famous amph-ph-phibians!

HELEN. (Bursts out laughing.) That’s just too absurd. Wild or domestic, tame or game, he can’t see anything that moves without shooting it!

KAHL. L-las’ night, I g-g-gunned down our ol’ s-s-sow.

LOTH. Seems that shooting is your primary occupation.”

Gerhard Hauptmann (15 november 1862 – 6 juni 1946)

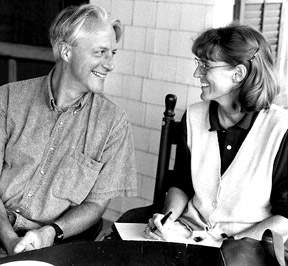

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Elizabeth Arthur werd geboren op 15 november 1953 in New York. In 1973 stopte zij met haar studie om te gaan doceren aan de National Outdoor Leadership School in Wyoming. Nadat zij in 1974 getrouwd was trokken zij en haar man naar Brits Columbia waar zij tot 1979 bleven. In 1978 studeerde Arthur alsnog af in Engels. In 1982 hertrouwde zij met de schrijver Steve Bauer en verhuisde zij uiteindelijk naar Indiana. Met een beurs kon zij in 1983 (Beyond the mountain) en in 1986 (Bad Guys) haar eerste twee romans schrijven.

Uit: Bring Deeps

„That afternoon, we both stayed angry; we could not stop, although we wished to. Language had led us to a place from which we could not wake at will to fly from it. How could this be? I think perhaps because our bodies spoke so well we failed to notice that our mouths spoke different dialects. We failed to notice, then or after, that our words could turn to stones, or were like ropes we had drawn forth and then become entangled in. And though our conversation needed to be untied as much as any dream in Gilgamesh, it never was, and there’s no magic which can change the evil consequence. We drove to Kirkwall, checked into the house where Bastian always roomed when he was there, and then, since it was three o’clock by then, had early tea, down in the parlor. We said few words until Sebastian said, ‘I have to get my mail. I have to work today.’

And I said, ‘Fine. You do that. I’ll take a walk and see this ugly town you’ve brought me to.’

‘Go see St Magnus,’ said Sebastian. ‘I’ve been there one too many times. I’ve had it up to here, in any case, with Viking savages. They went on the Crusades and slaughtered everyone in sight, then on their way back home, stopped by in Orkney to break in through the roof of the best Stone Age tomb in all of Europe. When that was not enough, they scrawled runes on its walls, claiming they had removed the chambers’ ’treasures”. Liars. There was no treasure.’

‘I know,’ I said, as short with him as he had ever been with me. ‘I know a lot that you don’t think I know.’

‘I’ll see you later, then,’ he said, and he was gone, and I was left enraged and desolate.

I pulled myself together. I felt a total fool, but put on a down vest, canvas jacket, boots, a woolen hat, before I went out walking, and that was good, because that way I wasn’t cut in half by the cold wind that gathered at each corner. Kirkwall wasn’t ugly, as I’d said. But neither was it like the rest of what I’d seen of Orkney — clear and cold and high and bright and welcoming. It was complex, with taut stone streets, and towered, tiered walls of stone, which seemed to have their windows peering darkly through them. Nor was it true, I n

oticed, that, as Bastian might imply, I felt the cold here more than other people. The day was August 4th, and from each chimney that I passed, smoke rose, although it was high summer in the Orkneys.“

Elizabeth Arthur (New York, 15 november 1953)

Elizabeth Arthur met haar man Steven Bauer

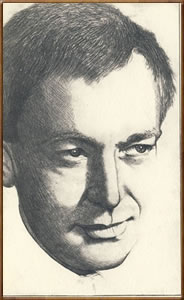

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Heinz Piontek werd geboren op 15 november 1925 Kreuzburg (Opper-Silezië). Bekend werd hij verrassend snel met de dichtbundels „Die Furt“ (1952) en „Die Rauchfahne“ (1953). In 1955 verscheen zijn eerste bundel met proza „Vor Augen“. In 1967 publiceerde hij de met de Münchner Literaturpreis bekroonde roman „Die mittleren Jahre“. In 1984 verscheen zijn sterk autobiografische roman „Zeit meines Lebens“, waarin hij over zijn kinderjaren en zijn jeugd in Opper-Silezië vertelde, twee jaar later gevolgd door “Stunde der Überlebenden“. Piontek maakte zich ook verdienstelijk als schrijver van hoorspelen, bloemlezer, vertaler (John Keats) en uitgever. Piontek moest in 1943 zo van de schoolbanken het leger in. In 1945 werd hij Amerikaans krijgsgevangene in Beieren. Hij werd vrijgelaten, maakte het gymnasium af en studeerde germanistiek. Vanaf 1948 was hij zelfstandig schrijver.

Die Furt

Schlinggewächs legt sich um Wade und Knie,

Dort ist die seichteste Stelle.

Wolken im Wasser, wie nahe sind sie!

Zögernder lispelt die Welle.

Waten und spähen – die Strömung bespült

Höher hinauf mir den Schenkel.

Nie hab ich so meinen Herzschlag gefühlt.

Sirrendes Mückengeplänkel.

Kaulquappenrudel zerstieben erschreckt,

Grundgeröll unter den Zehen.

Wie hier die Luft nach Verwesendem schmeckt!

Flutlichter kommen und gehen.

Endlose Furt, durch die Fährnis gelegt –

Werd ich das Ufer gewinnen?

Strauchelnd und zaudernd, vom Springfisch erregt

Such ich der Angst zu entrinnen.

Fischerhütte

Harte, wetterfarbne Planken

und die Tür im Sommer offen.

Auf der Eschenschwelle st

eh ich,

von der Finsternis betroffen.

Netze, eine Bootslaterne,

Wasserstiefel, Angelhaken,

der Südwester hängt am Nagel,

Strohsackkoje ohne Laken.

Hinterm Herd der Kienholzstapel,

warm und dünstig ist die Enge –

und im Dunkel die Geschichten

wunderbarer Fänge.

Heinz Piontek (15 november 1925 – 26 oktober 2003)

De Britse dichter en schrijver James Graham Ballard werd geboren in Shanghai op 15 november 1930. Zie ook alle tags voor J. G. Ballard op dit blog.

Crash (Fragment)

All the while I stared at those parts of Gabrielle’s body

Reflected in this nightmare technology of cripple controls.

I watched her thighs shifting against each other

The jut of her left breast under the strap of her spinal harness

The angular bowl of her pelvis

The hard pressure of her hand on my arm

She gazed back at me through the windshield

Playing with the chromium clutch treadle

As if hoping that something obscene might happen

It was I who first made love to her

In the rear seat of her small car

Surrounded by the bizarre geometry of the invalid controls

As I explored her body

Feeling my way among the braces and straps of her underwear

The unfamiliar planes of her legs and hips

Steered me into unique cul de sacs

Strange declensions of skin and musculature

Each of her deformities became a potent metaphor

For the excitements of a new violence

Her body with its angular contours

Its unexpected junctions of mucus membrane and hairline

Detrusor muscle and erectile tissue

Was a ripening anthology of perverse possibilies

As I sat with her by the airport fence in her darkened car

Her white breast in my hand lit by the ascending airliners

The shape and tenderness of her nipple seemed to rape my fingers

Her sexual acts were exploratory ordeals

J. G. Ballard (Shanghai, 15 november 1930)

De Duitse dichteres en schrijfster Liane Dirks werd geboren op 15 november 1965 in Hamburg. Zie ook alle tags voor Liane Dirks op dit blog.

Uit: Der Koch der Königin

„Das Mädchen allerdings brauchte er auch aus einem anderen Grund. Lange hatte er suchen müssen, viel hatte er erleben müssen, und noch meh rhatte er anderen angetan, bis er es fand. Es war etwas sehr Schlichtes, dem er in tausend Trug- und Zerrbildern nachgelaufen war. Hier erst hatte er es entdeckt, hier erst hatte er begriffen, hier, in diesem Land.

Es konnte eine Mango sein, oder eine sich rot öffnende Bananenblüte, es konnte ein schillernder, frisch aus dem Meer gezogener Snapper sein, der kraftvoll auf den Tisch schlug und in der LUft nach Wasser schnappte. Es konnte das Meer selber sein oder eine Handvoll Sand, der Anblick des Vulkans vor dem Abendhimmel oder das Gesicht eines Bettlers, der keineswegs blind war, s

ondern Sterne trug, wo andere ihre Augen haben.

Andres hatte nichts Geringeres als die Schönheit entdeckt, den Kern der Schönheit, die Essenz. Sie war es, nach der er sich sein Leben lang gesehnt hatte.

Das Mangel hatte ihn süchtig gemacht, die Fülle riss ihm zu sehr am Herzen. Es war das Maß, auf das es ankam, endlich hatte er es verstanden. Und das Mädchen hatte es. Es hatte genau das richtige Maß.“

Liane Dirks (Hamburg, 15 november 1965)

De Poolse dichter en schrijver Antoni Słonimski werd geboren op 15 november 1895 in Warschau. Hij groeide op als kind uit een joodse familie maar trad later toe tot de katholieke kerk. In 1919 richtte hij samen met Julian Tuwim en Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz de Skamander groep op, een groep van experimentele dichters. In 1939 ging hij in ballingschap, in 1940 vluchtte hij naar Londen. In 1951 keerde hij naar Polen terug en engageerde hij zich tegen het stalinisme en voor politieke liberalisering. Behalve gedichten schreef Słonimski ook theaterkritieken, feullietons en absurde verhalen.

Lyrics

I know, I’ll go on foot from the, station,

Even if it happened on a dark evening,

Can’t lose the way: along the track

Then left from the two acacia trees.

Tobacco flower fragrant in the darkness,

A sweetish scent of the horse manure

And somewhere a distant locomotive whistle

Long, melancholic, dolefully waning.

As it sometimes has been in my dreams,

I’ll recognize your voice when you ask: “Who’s there?”

And it will painfully grab me by the throat

The fear, the despair and the bliss of return.

“Who’s there?” – you will ask. I’ll say: “It’s me – Antoni

I am here.” One more step, one half – step.

And a trembling hand I’ll feel on my temple

And will hear the heart beat in the darkness.

“Did not think I’ll frighten you so!

Do not turn the lights on, let’s stay in the darkness,

Why look in the eyes, eyes no longer ours

When the hearts like in our youth are pounding?”

“Why you came back? It’s not good here.”

“I knew, but there was no solace for me,

I left here everything I possessed:

The common dreams of our young years.”

Vertaald door Stefan Golston

Antoni Słonimski (15 november 1895 – 4 juli 1976)

De Italiaanse schrijver Carlo Emilio Gadda werd geboren op 15 november 1893 in Milaan. Zie ook mijn blog van 15 november 2008.

Uit: That Awful Mess on the via Merulana (Vertaald door William Weaver)

“When they reached Via Merulana: the crowd. Outside the entrance, the black of the crowd, with its wreath of bicycle wheels. “Make way there. Police.” Everybody stood aside. The door was closed. A policeman was on guard: with two traffic cops and two carabinieri. The women were questioning them: the cops were saying to the women: “Stand aside.” The women wanted to know. Three or four, already, could be heard talking of the lottery numbers: they agreed on 17, all right, but they were having a spat over 13.

The two men went up to the Balducci home, the hospitable home that Ingravallo knew, you might say, in his heart. On the stairway, a parleying of shadows, the whispers of the women of the building. A baby cried. In the entrance hall . . . nothing especially noticeable (the usual odor of wax, the usual neatness) except for two policemen, silent, awaiting instructions. On a chair, a young man with his lead in his hands. He stood up. It was Doctor Valdarena. Then the concierge appeared, emerging, grim and pudgy, from the shadow of the hall. Nothing remarkable, you would have said: but as soon as they had entered the dining room, on the parquet floor, between the table and the little sideboard, on the floor . . . that horrible thing.

The body of the poor signora was lying in an infamous position, supine, the gray wool skirt and a white petticoat thrown back, almost to her breast: as if someone had wanted to uncover the fascinating whiteness of that dessous, or inquire into its state of cleanliness. She was wearing white underpants, of elegant jersey, very fine, which ended halfway down the thighs with a delicate edging. Between the edging and the stockings, which were a light-shaded silk, the extreme whiteness of the flesh lay naked, of a chlorotic pallor: those two thighs, slightly parted, on which the garters-a lilac hue-seemed to confer a distinction of rank, had lost their tepid sense, were already becoming used to the chill: to the chill of the sarcophagus and of man’s taciturn, final abode. The precise work of the knitting, to the eyes of those men used to frequenting maidservants, shaped uselessly the weary proposals of a voluptuousness whose ardor, whose shudder, seemed to have barely been exhaled from the gentle softness of that hill, from that central line, the carnal mark of the mystery … the one that Michelangelo (Don Ciccio mentally saw again his great work, at San Lorenzo) had thought it wisest to omit. Details! Skip it!”

Carlo Emilio Gadda (15 november 1893 – 21 mei 1973)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 15e november ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag.