De Zuid-Afrikaanse dichter en schrijver Tatamkhulu Afrika werd geboren op 7 december 1920 in Egypte. Zie ook alle tags voor Tatamkhulu Afrika op dit blog.

Uit: Bitter Eden

“Down at the dead end of the beach, I wash my face in the tideless sea, stare out over the still darkened warm-as-blood water to the skyline that has become a cage’s prohibitive ring, go back, then, to the higher, now sunlit land where silent men are smashing rifles over rocks with the ferocity of those who wrestle serpents with their bare hands. I pass what is clearly an officer’s tent. It is dug in until only the ridge shows, neat steps leading down. Outside, a batman is washing a china plate, saucer, cup, his pug-dog peasant’s face seemingly unconcerned, but it does not raise from its staring down at the trembling of the hands. I pass another tent sunk in the sand. Again the ubiqui-tous robot’s playing games, denying midnight now. Frenziedly the hands polish the buttons on an officer’s tunic, button-stick inserted round the buttons so that the Brasso will not whiten the sullen cloth, bring upon the hands a comic wrath. The tunic’s shoulder flaps flaunt a crown. I am thinking ‘Christr, beating back bile. He is coming towards me, studying the anonymity of my fatigues, two pips glinting on his shoulders, sandy hair lifting in the awakening wind. The hair, the prissy pursing of the lips, the button mushroom eyes, warn of the worst of the breed and I snap him my still smart training college salute. He floppy-chops an arm back, barks, ‘Unit and rank?’ I think to tell him I am Colonel this-or-that because how would he — now — ever find out otherwise, but the solemnness in the air like bells’ dissuades me and I say, ‘Ser-geant. Second Divisional Headquarters. Sir!’ His eyes widen a little as he balances between surprise and what I suspect is a chronic tendency to disbelieve. ‘Div. H.Q? What do you do at Div. H.Q.?’ There is a slight em-phasis on the ‘you’. `Chemical Warfare Intelligence and Training. Sir!’ He is impressed and it shows in a slight inclining to me of stance and tone, and something like a greediness of the eyes, which makes no sense and which I dismiss as a stress-induced fancifulness of the mind. `Do you want to hand yourself over like a sheep or make a break?’ His voice is casual but his glance is sharp and I hear myself saying, ‘Make a break,’ even though previously there had been no thought of that in my mind. I am honest enough to admit that I am no hero and, even now, I am painfully aware that my excitement at the prospect of escape only slightly exceeds my congenital dread. `Get in that truck then,’ he says and indicates a battered three-tonner a few paces off. ‘Where’s your kit? Are you armed?’ `No kit, sir. No arms.’ Even as the words still sound, I realize what I’m saying and I hump not my kit but my shame as I for the first time am faced by the fact that I never even thought of retrieving my kit from the anti-gas truck before I set the latter alight.“

Tatamkhulu Afrika (7 december 1920 – 23 december 2002)

Cover

De Duits-Oostenrijkse schrijver, presentator en cabaretier Dirk Stermann werd geboren op 7 december 1965 in Duisburg. Zie ook alle tags voor Dirk Stermann op dit blog.

Uit: Kurz & Klein

„Mein Name ist Caspar. Manchmal gehe ich gern in den Wald. Manchmal aber auch nicht. Im Wald da gibt es Bäume. Ich kenne Eichen und Fichten und die Bäume, die man zu Weihnachten in die Häuser stellt. Die heißen Tannen. Die meisten Bäume sind ganz schön hoch, es gibt aber auch welche, die sind nicht so hoch. Wenn die Hohen umkippen, muss man ganz schnell in Deckung gehen, weil sonnst hauen die einen um. Ich hab deswegen Angst vor den hohen Bäumen. Die Kleinen sind ja nicht so schlimm. Wenn die umkippen. find ich das lustig. Meine Freunde und ich machen das oft. Im Wald da gibt es sonnen Tümpel oder so und da drin sind Frösche. Viele Frösche. Denen stecken wir ein Strohhalm hinten rein und blasen die dann auf. Die werden dann ganz dick, dann kann man Fußball mit den spielen. Wer den dicksten bläst, hat gewonnen. Meistens gewinn ich nie nicht, :aber manchmal doch. Da gibt es auch noch so andere Tiere, die erschrecken wir immer. Man braucht nur in die Hände klatschen, dann hauen die schon ah. So feige sind die. Der Michael ist mein Freund und hat gesagt, daß er Tiere doof findet. Das find ich nicht. Ich finde, man kann sie ja immerhin aufblasen und erschrecken und so. Und viele Menschen haben ja auch Tiere zu Hause. Nicht nur Weihnachten wie die Tannen, sondern ich glaub immer. Aber das sind ja auch ganz andere Tiere. Nicht so richtige. Die beißen einen ja auch. Michael wurde neulich von einem gebissen. Der mußte dann ins Krankenhaus und da haben die den mit einer Nadel und einem Nähgarn genäht. Ich glaub, ich find Tiere doch doof. Am liebsten spiele ich bei uns auf der Straße.“

Dirk Stermann (Duisburg, 7 december 1965)

De Oostenrijkse dichter en schrijver Johann Nepomuk Eduard Ambrosius Nestroy werd geboren in Wenen op 7 december 1801. Zie ook alle tags voor Johann Nestroy op dit blog.

K.-Jammer

Diese graue Wolkenschar

Stieg aus einem Meer von Freuden;

Heute muß ich dafür leiden,

Daß ich gestern glücklich war.

Ach, in Wermut hat verkehrt

Sich der Nektar! Ach, wie quälend,

Katzenjammer, Hundeelend

Herz und Magen mir beschwert!

Ein steiler Felsen ist der Ruhm

Ein steiler Felsen ist der Ruhm,

Ein Lorbeerbaum wächst darauf.

Viel kraxeln drum und dran herum,

Doch wenig kommen ‘nauf;

Darneben ist ein Präzipiß,

’s geht kerzengrad hinab,

Da drunnt’ ein Holz zu finden is,

Es heißt der Bettelstab.

Wer nicht enorm bei Kräften is,

Soll nicht auf’n Felsen steig’n.

Er rutscht und fallt ins Präzipiß,

Viel Beispiel tun das zeig’n…

Die Mittelstraßen ist ein breiter Raum,

Die Fahrt kommod talab,

Es wachst zwar drauf kein Lorbeerbaum,

Doch auch kein Bettelstab.

Heute ist Tag der Lyrik

O Knute, o Knute!

Die schwingen man tute,

Machst Wirkung sehr gute

Bei frevelndem Mute.

Was dem Kinde die Rute,

Ist dem Volke die Knute;

Du stillest die Wute

Rebellischem Blute.

Das alles, das tute

Die Knute, die Knute!

Wehalb ich mich spute,

In einer Minute

Poetischer Glute

Schrieb ich an die Knute

Dies Gedichtchen, dies gute.

Johann Nestroy (7 december 1801 – 25 mei 1862)

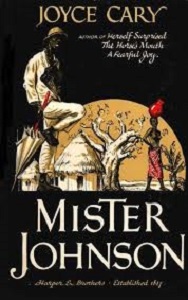

De Brits – Ierse schrijver Arthur Joyce Lunel Cary werd geboren op 7 december 1888 in Derry, Ierland. Zie ook alle tags voor Joyce Cary op dit blog.

Uit: Mr. Johnson

“No officer who has ever commanded a Nigerian company can forget the Hausa Farewell, that tune upon the bugles played as he rides away for the last time. But I don’t know why, having met and greeted plenty of veterans, I remember so vividly that scene on the parade ground—perhaps only because I was taken by surprise, I can still see the sergeant’s face, the men running; I can’t forget their grins (and laughter—an African will laugh loudly with pleasure at any surprise), the hands stretched out, the shouts of greeting from the back where some young and short soldier felt excluded. It is not true that Africans are eager but fickle. They remember friendship quite as long as they strongly feel it.

As for the style of the book, critics complained of the present tense. And when I answered that it was chosen because Johnson lives in the present, from hour to hour, they found this reason naïve and superficial. It is true that any analogy between the style and the cast of a hero’s mind[Pg 8] appears false. Style, it is said, gives the atmosphere in which a hero acts; it is related to him only as a house, a period, is related to a living person.

But this, I think, is a view answering to a critical attitude which necessarily overlooks the actual situation of the reader. For a critic, no doubt, style is the atmosphere in which the action takes place. For a reader (who may have as much critical acumen as you please, but is not reading in order to criticize), the whole work is a single continuous experience. He does not distinguish style from action or character.

This is not to pretend that reading is a passive act. On the contrary, it is highly creative, or recreative; itself an art. It must be so. For all the reader has before him is a lot of crooked marks on a piece of paper. From those marks he constructs the work of art which conveys idea and feeling. But this creative act is largely in the subconscious. The reader’s mind and feelings are intensely active, but though he himself is fully aware of the activity (it is part of his pleasure) he is absorbed, or should be absorbed, in the tale. A subconscious creative act may be a strange notion, but how else can one describe the passage from printer’s ink into active complex experience. After all, a great deal of rational and constructive activity goes on in the subconscious. We hear of people who dream solutions of difficult mathematical problems. “

Joyce Cary (7 december 1888 – 29 maart 1957)

Cover

De Franse filosoof en toneelauteur Gabriel Marcel werd geboren op 7 december 1889 in Parijs. Zie ook alle tags voor Gabriel Marcel op dit blog.

Uit:The mystery of being

“One might note here, in passing, that in our modern world, because of its extreme technical complication, we are, in fact, condemned to take for granted a great many results achieved through long research and laborious calculations, research and calculations of which the details are bound to escape us.

One might postulate it as a principle, on the other hand, that in an investigation of the type on which we are now engaged, a philosophical investigation, there can be no place at all for results of this sort. Let us expand that: between a philosophical investigation and its final outcome, there exists a link which can not be broken without the summing up itself immediately losing all reality. And of course we must also ask ourselves here just what we mean, in this context, by reality.

We can come to the same conclusions starting from the other end. We can attempt to elucidate the notion of philosophical investigation directly. Where a technician, like the chemist, starts off with some very general notion, a notion given in advance of what he is looking for, what is peculiar to a philosophical investigation is that the man who undertakes it cannot possess anything equivalent to that notion given in advance of what he is looking for. It would not, perhaps, be imprecise to say that he starts off at random ; I am taking care not to forget that this has been sometimes the case with scientists themselves, but a scientific result achieved, so to say, by a happy accident acquires a kind of purpose when it is viewed retrospectively ; it looks as if it had tended towards some strictly specific aim. As we go on we shall gradually see more and more clearly that this can never be the case with philosophic investigation.

On the other hand, when we think of it, we realize that our mental image of the technician of the scientist, too, for at this level the distinction between the two of them reaches vanishing point is that of a man perpetually carrying out operations, in his own mind or with physical objects, which anybody could carry out in his place. The sequence of these operations, for that reason, can be schematized in universal terms. I am abstracting here from the mental gropings which are inseparable, in the individual scientist s history, from all periods of discovery. These gropings are like the useless roundabout routes taken by a raw tourist in a country with which he has not yet made himself familiar. Both are destined to be dropped and forgotten, for good and all, once the traveller knows the lie of the land.”

Gabriel Marcel (7 december 1889 – 8 oktober 1973)

Parijs in de Adventstijd

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Willa Cather werd geboren op 7 december 1873 in de buurt van Winchester, Virginia. Zie ook alle tags voor Willa Cather op dit blog.

Uit:Behind the Singer Tower

“It was a hot, close night in May, the night after the burning of the Mont Blanc Hotel, and some half dozen of us who had been thrown together, more or less, during that terrible day, accepted Fred Hallet’s invitation to go for a turn in his launch, which was tied up in the North River. We were all tired and unstrung and heartsick, and the quiet of the night and the coolness on the water relaxed our tense nerves a little. None of us talked much as we slid down the river and out into the bay. We were in a kind of stupor. When the launch ran out into the harbor, we saw an Atlantic liner come steaming up the big sea road. She passed so near us that we could see her crowded steerage decks.

“It’s the Re di Napoli,” said Johnson of the “Herald.” “She’s going to land her first cabin passengers to-night, evidently. Those people are terribly proud of their new docks in the North River; feel they’ve come up in the world.”

We ruffled easily along through the bay, looking behind us at the wide circle of lights that rim the horizon from east to west and from west to east, all the way round except for that narrow, much-traveled highway, the road to the open sea. Running a launch about the harbor at night is a good deal like bicycling among the motors on Fifth Avenue. That night there was probably no less activity than usual; the turtle-backed ferryboats swung to and fro, the tugs screamed and panted beside the freight cars they were towing on barges, the Coney Island boats threw out their streams of light and faded away. Boats of every shape and purpose went about their business and made noise enough as they did it, doubtless. But to us, after what we had been seeing and hearing all day long, the place seemed unnaturally quiet and the night unnaturally black. There was a brooding mournfulness over the harbor, as if the ghost of helplessness and terror were abroad in the darkness. One felt a solemnity in the misty spring sky where only a few stars shone, pale and far apart, and in the sighs of the heavy black water that rolled up into the light. The city itself, as we looked back at it, seemed enveloped in a tragic self-consciousness.”

Willa Cather (7 december 1873 – 24 april 1947)

Cover

De Amerikaanse taalkundige, mediacriticus en anarchistisch denker Noam Chomsky werd geboren in Philadelphia op 7 december 1928. Zie ook alle tags voor Noam Chomsky op dit blog.

Uit: Propaganda, American-style

“Like the Soviets in Afghanistan, we tried to establish a government in Saigon to invite us in. We had to overthrow regime after regime in that effort. Finally we simply invaded outright. That is plain, simple aggression. But anyone in the U.S. who thought that our policies in Vietnam were wrong in principle was not admitted to the discussion about the war. The debate was essentially over tactics.

Even at the peak of opposition to the U.S. war, only a minuscule portion of the intellectuals opposed the war out of principle–on the grounds that aggression is wrong. Most intellectuals came to oppose it well after leading business circles did–on the “pragmatic” grounds that the costs were too high.

Strikingly omitted from the debate was the view that the U.S. could have won, but that it would have been wrong to allow such military aggression to succeed. This was the position of the authentic peace movement but it was seldom heard in the mainstream media. If you pick up a book on American history and look at the Vietnam War, there is no such event as the American attack on South Vietnam. For the past 22 years, I have searched in vain for even a single reference in mainstream journalism or scholarship to an “American invasion of South Vietnam” or American “aggression” in South Vietnam. In America’s doctrinal system, there is no such event. It’s out of history, down Orwell’s memory hole.

If the U.S. were a totalitarian state, the Ministry of Truth would simply have said, “It’s right for us to go into Vietnam. Don’t argue with it.” People would have recognized that as the propaganda system, and they would have gone on thinking whatever they wanted. They would have plainly seen that we were attacking Vietnam, just as we can see the Soviets are attacking Afghanistan.

People are much freer in the U.S., they are allowed to express themselves. That’s why it’s necessary for those in power to control everyone’s thought, to try and make it appear as if the only issues in matters such as U.S. intervention in Vietnam are tactical: Can we get away with it? There is no discussion of right or wrong.

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. propaganda system did its job partially but not entirely. Among educated people it worked very well. Studies show that among the more educated parts of the population, the government’s propaganda about the war is now accepted unquestioningly. One reason that propaganda often works better on the educated than on the uneducated is that educated people read more, so they receive more propaganda. Another is that they have jobs in management, media, and academia and therefore work in some capacity as agents of the propaganda system–and they believe what the system expects them to believe. By and large, they’re part of the privileged elite, and share the interests and perceptions of those in power.”

Noam Chomsky (Philadelphia, 7 december 1928)

De Oostenrijkse schrijver en columnist Friedrich Kilian Schlögl werd geboren op 7 december 1821 in de Weense voorstad Laimgrube (nu Wenen). Zie ook alle tags voor Friedrich Schlögl op dit blog.

Uit: Veni sancte spiritus! (Wiener Blut)

„Das war mir immer ein Räthsel; warum soll die Furcht der Anfang der Weisheit sein, wenn gerade die unverschämtesten Subjecte in diesem Jammerthale am klügsten fahren, und warum will die Menschheit überhaupt weise werden, wenn doch unstreitig die allerdümmsten ihrer Genossen zeitlebens vom Glücke begünstigt bleiben?

Aber man drillt uns fort und fort nach dem altmodischen Muster und mir drillen wieder unsere Sprößlinge, nur recht »weise« zu werden, und wir wissen nicht genug »lehrreiche« Bücher aufzutreiben, die die stupendeste Weisheit in brochürtem Zustande auf so und so vielen Druckbogen enthalten, welche Weisheit, in mäßige Dosen (Lectionen) vertheilt, löffel(seiten)weise genossen, den Lernbegierigen nach dem aufliegenden Schulprogramme in der gesetzlich bemessenen Zeit so vollkommen »reif« macht, daß er augenblicklich z. B. Verwaltungsrath der Lemberg-Czernowitzer Bahn, oder einer beliebigen, selbst der dunkelsten Bank werden könnte, wenn die bezüglichen Posten nicht von anderen »Reifen« bereits besetzt wären.

Sei es wie es sei; aber die letzte Septemberwoche war mir stets ein tragikomisches Kaleidoskop, wenn ich sah, wie sich Alt und Jung für den ersten oder abermaligen Schulanfang rüstet und welche kostspieligen Apparate mitunter benützt werden, um das junge Reis zu einem fruchtbringenden Baume, den unwissenden Knirps zu einem soi-disant »nützlichen Staatsbürger« heranzubilden. Welche herbe Opfer werden da oft gebracht und welch’ Schweiß klebt, um mich recht unbildlich auszudrücken, an diesen, außerdem noch mit einem Agio belasteten Banknoten, welche die obligaten Vehikel der Gelehrsamkeit, genannt Schulbücher, verschlingen.

Nun fällt mir nichts weniger ein, als gegen den in unserer wissenschaftlich gemäßigten Zone ohnehin nur sporadisch auftretenden »Büchereinkauf« zu predigen. Meine geehrten Landsleute treiben den Büchersport bekanntlich nur in zahmster Weise und die wenigen bibliothekarischen Dilettanten, welche die Metropole des Backhendlthums birgt, gehören zu den kulturhistorischen Curiositäten. Ja selbst die wohlhabendere Classe des Bürgerstandes findet es überhaupt meist »unbegreiflich«, für ein Buch – Geld auszulegen, und wenn z. B. der lebenslustige Hausherr X. und sein »Aeltester«, sich nicht lange besinnen, ihrem Leibfiaker einen Viertel Eimer Bier zu zahlen, falls es diesem gelingt, sie in fünfundsechzig Minuten von Schottenfeld zum »rothen Stadl« zu führen, so werden sie sicher die Zumuthung, etwa »Goethe’s Faust«, nach der neuen Classiker-Verschleuderung um zwanzig Kreuzer zu kaufen, für eine unnöthige »Geldverschwendung« erklären.“

Friedrich Schlögl (7 december 1821 – 7 oktober 1892)

Laimgrube (Wenen) Mariahilfer Straße, 1901

De Duitse dichter Samuel Gottlieb Bürde werd geboren op 7 december 1753 in Breslau. Zie ook alle tags voor Samuel Gottlieb Bürde op dit blog.

Wir gönnen jedem Glücklichen

Wir gönnen jedem Glücklichen

des Reichtums goldnen Fund;

er sei nicht stolz, noch poch er drauf,

das Glück geht unter und geht auf.

Sein Fußgestell ist rund.

Der Redliche, mit dem das Glück

stiefmütterlich es meint,

der seinem Schiffbruch kaum entschwimmt,

und nackend ans Gestade klimmt,

der finde einen Freund!

Freut euch des Herrn, ihr Frommen

Freut euch des Herrn, ihr Frommen,

und heißt mit lautem Jubelruf

das junge Jahr willkommen

und preist ihn, der den Frühling schuf!

Seht, wie im Blumenkleide

die Wiese lieblich prangt!

Nur der fühlt wahre Freude,

der Gott von Herzen dankt.

Auf, jeder pflügt und säe und singe froh dazu:

Ehr’ sei Gott in der Höhe, auf Erden Fried und Ruh!

Samuel Gottlieb Bürde (7 december 1753 – 28 april 1831)

Breslau – Pools: Wrocław, in de Adventstijd (Geen portret beschikbaar)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 7e december ook mijn blog van 7 december 2014 deel 2.