De Vlaamse dichteres Patricia Lasoen werd geboren op 25 september 1948 in Brugge. Zie ook mijn blog van 25 september 2006.

Reïncarnatie

mijn voetjes warmend

hoog tussen je zachte dijen

denk ik plots

aan die kale man

die vroeger de piano stemde

en alleen maar melk en

regenwater dronk.

Hij geloofde aan reïncarnatie en

– verstrooid de snaren toetsend –

heeft hij op een dag verteld

dat ik vroeger een prinses was

of de dochter van een Indianenstamhoofd

en Kiruka heette.

Zelf zou hij terugkeren

als bruingestreepte kater.

Patricia Lasoen (Brugge, 25 september 1948)

De Spaanse schrijver Carlos Ruiz Zafón werd geboren op 25 september 1964 in Barcelona. Zie ook mijn blog van 25 september 2006.

Uit: Der Friedhof der Vergessenen Bücher (Der Schatten des Windes,Vertaald door Peter Schwaar)

“Ich erinnere mich noch genau an den Morgen, an dem mich mein Vater zum ersten Mal zum Friedhof der Vergessenen Bücher mitnahm. Die ersten Sommertage des Jahres 1945 rieselten dahin, und wir gingen durch die Straßen eines Barcelonas, auf dem ein aschener Himmel lastete und dunstiges Sonnenlicht auf die Rambla de Santa Mónica filterte. “Daniel, was du heute sehen wirst, darfst du niemandem erzählen”, sagte mein Vater. “Nicht einmal deinem Freund Tomás. Niemandem.”

“Auch nicht Mama?” fragte ich mit gedämpfter Stimme.

Mein Vater seufzte hinter seinem traurigen Lächeln, das ihn wie ein Schatten durchs Leben verfolgte.

“Aber natürlich”, antwortete er gedrückt. “Vor ihr haben wir keine Geheimnisse. Ihr darfst du alles erzählen.”

Kurz nach dem Bürgerkrieg hatte eine aufkeimende Cholera meine Mutter dahingerafft. An meinem vierten Geburtstag beerdigten wir sie auf dem Friedhof des Montjuïc. Ich weiß nur noch, daß es den ganzen Tag und die ganze Nacht regnete und daß meinem Vater, als ich ihn fragte, ob der Himmel weine, bei der Antwort die Stimme versagte. Sechs Jahre später war die Abwesenheit meiner Mutter für mich noch immer eine Sinnestäuschung, eine schreiende Stille, die ich noch nicht mit Worten zum Verstummen zu bringen gelernt hatte. Mein Vater und ich lebten in einer kleinen Wohnung in der Calle Santa Ana beim Kirchplatz. Die Wohnung lag direkt über der von meinem Großvater geerbten, auf Liebhaberausgaben und antiquarische Bücher spezialisierten Buchhandlung, einem verwunschenen Basar, der, wie mein Vater hoffte, eines Tages in meine Hände übergehen würde. Ich wuchs inmitten von Büchern auf und gewann auf zerbröselnden Seiten, deren Geruch mir noch immer an den Händen haftet, unsichtbare Freunde. Als Kind lernte ich damit einzuschlafen, daß ich meiner Mutter im dämmrigen Zimmer die Ereignisse zwischen Morgen und Abend, meine Abenteuer in der Schule erklärte und was ich an diesem Tag gelernt hatte. Ich konnte ihre Stimme nicht hören und ihre Berührung nicht fühlen, aber ihr Licht und ihre Wärme glühten in jedem Winkel der Wohnung, und mit der Zuversicht dessen, der seine Jahre noch an den Fingern abzählen kann, dachte ich, wenn ich nur die Augen schlösse und mit ihr spräche, könnte sie mich vernehmen, wo immer sie auch sein mochte. Manchmal hörte mir mein Vater im Eßzimmer zu und weinte verstohlen.

Ich erinnere mich, daß ich in jener Junimorgendämmerung schreiend erwachte. Das Herz hämmerte mir in der Brust, als wollte sich die Seele einen Weg bahnen und treppab stürmen. Erschrocken stürzte mein Vater ins Zimmer und nahm mich in die Arme, um mich zu trösten.”

Carlos Ruiz Zafón (Barcelona, 25 september 1964)

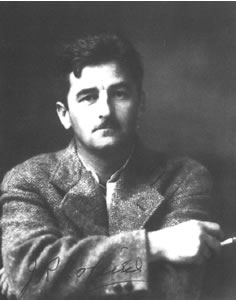

De Amerikaanse schrijver William Faulkner werd geboren op 25 september 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi. Zie ook mijn blog van 25 september 2006.

Uit: As I Lay Dying

“Jewel and I come up from the field, following the path in single file. Although I am fifteen feet ahead of him, anyone watching us from the cottonhouse can see Jewel’s frayed and broken straw hat a full head above my own.

The path runs straight as a plumb-line, worn smooth by feet and baked brick-hard by July, between the green rows of laidby cotton, to the cottonhouse in the center of the field, where it turns and circles the cottonhouse at four soft right angles and goes on across the field again, worn so by feet in fading precision.

The cottonhouse is of rough logs, from between which the chinking has long fallen. Square, with a broken roof set at a single pitch, it leans in empty and shimmering dilapidation in the sunlight, a single broad window in two opposite walls giving onto the approaches of the path. When we reach it I rum and follow the path which circles the house. jewel, fifteen feet behind me, looking straight ahead, steps in a single stride through the window. Still staring straight ahead, his pale eyes like wood set into his wooden face, he crosses the floor in four strides with the rigid gravity of a cigar store Indian dressed in patched overalls and endued with life from the hips down, and steps in a single stride through the opposite window and into the path again just as I come around the comer. In single file and five feet apart and jewel now in front, we go on up the path toward the foot of the bluff.

Tull’s wagon stands beside the spring, hitched to the rail, the reins wrapped about the seat stanchion. In the wagon bed are two chairs. Jewel stops at the spring and takes the gourd from the willow branch and drinks. I pass him and mountthe path, beginning to bear Cash’s saw.

William Faulkner (25 september 1897 – 6 juli 1962)

De Duitse schrijver en literatuurwetenschapper Herbert Heckmann werd geboren op 25 september 1930 in Frankfurt am Main. Hij studeerde aan de Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität filosofie, germanistiek en geschiedenis.. Vanaf 1958 was hij vijf jaar wetenschqappelijk assistent aan de universiteiten van Heidelberg en Münster. In 1965 ging hij voor twee jaar als gastdocent naar de Northwestern University Evanston/Illinois. Van 1963 tot 1979 werkte hij voor de Neue Rundschau. Van 1980 tot 1995 was hij hoogleraar aan de Hochschule für Gestaltung Offenbach am Main. Heckmann schreef romans, verhalen en kinderboeken. Voor zijn prozadebuut kreeg hij in 1959 een beurs van de Villa Massimo. In 1963 kreeg hij de Bremer Literaturpreis.

Uit: ‘Stefan George heute’

” (…) Tatsache ist, daß Stefan George der deutschen Sprache einige sehr schöne Gedichte geschenkt hat…In dem Zyklus Das Jahr der Seele, besonders im ersten Teil, der den Titel Nach der Lese trägt, ist der Herbst nicht nur als Jahreszeit zu nehmen; er ist auch ein historischer Augenblick, ein Wissen um die Dekadenz. “Komm in den totgesagten park…” So beginnt die erste Zeile des ersten Gedichts. Auch hier der Park, die vom Menschen besorgte Natur. Die Pflanzen entfalten einen letzten Glanz.

“Die späten rosen welken noch nicht ganz,

Erlese, küsse sie und flicht den kranz.”

Stefan George zeigt den letzten Aufstand der Schönheit vor dem Vergehen. Fast behutsam zählt er die einzelnen Ereignisse und Dinge auf, preist ihre Farben, die Vorboten des Verwelkens. Keinem anderen Herbstgedicht in der deutschen Literatur, die an Herbstgedichten wahrlich nicht arm ist, gelingt es so, die verführerische Schönheit des Herbstes einzufangen, so sehr die Verzauberung anzudeuten, die die herbstlich wuchernde Schönheit ausübt. Die letzte Entfaltung des Lebens im schon totgesagten Park wird hinübergerettet ins Gedicht.

“Und auch was übrig blieb vom grünen leben

Verschwinde leicht im herbstlichen gesicht.” (…) “

Herbert Heckmann (25 september 1930 – 18 oktober 1999)