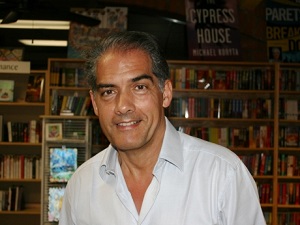

De Nederlandse schrijver Arnon Grunberg werd geboren in Amsterdam op 22 februari 1971. Zie ook alle tags voor Arnon Grunberg op dit blog.

Uit: Birthmarks (Moedervlekken, vertaald door Joni Zwart)

“Kadoke wants to ring the doorbell, but the grass makes him hesitate. He picks up the hose and starts watering the front garden, the trees, the plants, the lawn. The son, who, as was expected of him, became a psychiatrist, is looking after the garden. Every once in a while he played badminton here with his father. Th ose days are gone; now the grass is mainly looked at, like an old familiar painting, still beautiful. It has not rained for almost ten days; yellow patches have started to form on the grass. For years it had been well maintained, this garden, a labour of love, or at least of a perseverance and a sense of responsibility indistinguishable from love. Perse-verance is love too – the refusal to give up, the reluctance to lose, to die; all are forms of love. How very tragic that a short period of drought can wreak such havoc.It is early morning, but already warm. A neighbour is staring at him, but Kadoke pretends not to see her. Th ere is nothing remarkable about this scene: the son watering the withered garden, the son who cares for this, that and the other, the son who lives so others do not have to die.But it is not possible for him to care for everything, or rather: his care does not always have the desired effect. Th atis the problem. He has given the girls instructions, some he has written in English and stuck on a kitchen cupboard and while watering the grass, he begins to wonder why his simple instructions have not been followed.‘Please, water the garden when the lawn is dry’; surely is not that hard to understand. Th e young women looking after his mother can easily water the garden in between car-ing for her. No need to keep such a close watch on mother that there is no time left for the grass.Kadoke knows who he is: Otto Kadoke, calm, dedicated but not overly empathic, that is no good for the calmness, no good for the treatment, the doctor should not come too close. Th e emphasis is on the third syllable, it is Kadoké, but when people mispronounce his name, he does not correct them. What is a name? At most a history one has to relate to. Th ey can call him ‘doctor’ as well. He signs offi cial pa-pers with O. Kadoke.He is named after Otto Frank, a friend of the family, although it seems his mother never liked the famous Otto much.He had resented his fi rst name when he was still a child, as if his parents had intended to pull a trick on him. Al-most everyone comes to terms with his name, but he did not, and at some point during primary school he started calling himself Oscar. To friends he is Oscar, to patients doctor Kadoke. He is a man with no fi rst name. His wife only called him Otto when they were fi ghting. Th e last one and a half year of their marriage, she almost exclusively addressed him by Otto.”

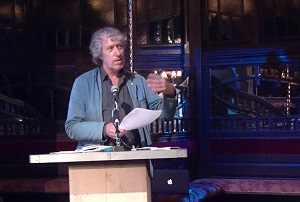

De Nederlandse schrijver, dichter, literatuurcriticus en columnist Rob Schouten werd geboren in Hilversum op 22 februari 1954. Zie ook alle tags voor Rob Schouten op dit blog.

Een heel behoorlijk natuurgedicht

De scepsis langzaam weggestorven

en het laatste voorbehoud

met de spotvogels vertrokken

naar het heidense Zuiden

wordt het tijd om te gaan sneeuwen,

eerst langzaam, daarna dichter,

tot alles blanco is en onverlicht,

je reinste Middeleeuwen.

Mooi zo, dan nu maar eens een zwerver

aan laten kloppen. Volluk! Hongur!

Het licht in de boerderij gaat aan,

de zoon wordt onderwijzer, kleinzoon prof

en voor je het beseft

is het vakantie in Toscane.

Liefde

Het grote woord houdt hier niet van, schudt zenuwachtig,

zwijgt pijnlijk, staart wat voor zich uit, Say Cheese, vogeltje!

Mis. Te bewogen. Nog maar eens. Een ander licht.

Verstandhouding, samen veel praten. Beter zo?

Over jeugd en wat het is, alles ook wel

eens op een bed? Stil blijven staan! Een bedrand dan.

Misschien het holst van een theater met opeens

een hand tussen de garderobe en van schrik

nog twee vurig buiten bereik der camera?

Of daarna wandelen, de waarheid onder ogen…

Houdt godverdomme even van elkaar, ja kan dat?

Ik doe ook maar mijn werk en lig liever in bed.

Kreutzersonate

Adagio en Con moto is hij doorgedrongen

en blijft dat ook. Ga weg denkend, in godsnaam weg,

word ik doorlopend in mijn luisteren gedwongen

al hoor ik haast geen woord van wat hij zegt.

Zijn wié vermoord? Hoezo, je banksaldo? Hij legt

de klemtoon daar waar ik hem kwalijk moet gaan nemen

terwijl ik alsmaar grapjes in mij overleg.

Valt er soms iets te lachen? Niets mag ik niet vernemen.

Hij toont mij schaamteloos gezwellen en oedemen.

Ik krijg het warm en kijk verlangend naar het raam;

hij staat het kolossaal voor me te zemen.

Soms hoor ik zwijgend hoe ik zelf ook iets uitkraam

– Orpheus! Orpheus! – Ach, je moet maar… Ach, zo, zo,

met dichtgeschroefde keel. Con moto en Adagio.

De Nederlandse dichter Ruben van Gogh werd geboren in Dokkum op 22 februari 1967. Zie ook alle tags voor Ruben van Gogh op dit blog.

Niet bang zijn

Niet bang zijn, niet bang zijn: zelfs onder water

gaat het leven door; alleen niet voor ons

— een detail dat je maar beter kan vergeten.

Nee, dan het grotere en diepere dat ons

omringt bij het eeuwige geworstel

op het droge; dat zou wel eens de troost

van het hoge kunnen zijn. De grond

is hard, de lucht is scherp: maar zacht

zijn de momenten dat je om het kolderieke

lachen moet. Een glimlach, meer zit er

niet in. Er is een einde, er is een begin.

Niet bang zijn, niet bang zijn; stel het bang

zijn uit, en op het moment dat je bang zou

móeten zijn, sluit het water zich onherroepelijk

om je heen. En overal begint weer leven:

kolderiek, lach maar — je zit er middenin.

Ooggetuige

toen ik door het

sluiten van de ramen

de wereld buitensloot,

wie hoorde toen

het radeloze tikken

van allerlei insecten,

wie het snakken van de

bladergroene kamerplanten

naar meer, naar overdaad,

wie het muzikale zoemen en weer

afslaan van de oude koelkast,

waarin kaas en eieren in

bedden sla ten onder gingen?

ik vraag u hier:

wie was ooggetuige

van mijn behoedzame

bewegingen van hier

naar daar,

naar de keuken,

naar de slaapkamer,

naar de kelder bijvoorbeeld,

wie?

iedereen ging dood

toen ik de ramen sloot.

Nee, niet een kind

nee, niet een kind

niet dit kind dan

gescheiden van

zijn ouders die elders

geld maken moeten

kilometers vreten

vele, vele kilometers

vreten voor hun kind

dit kind moet ze

nog afleggen, later

als het lukt

als het maar gelukkig wordt

nietwaar? niet zomaar

oversteekt, ergens

tussen al die kilometers

door

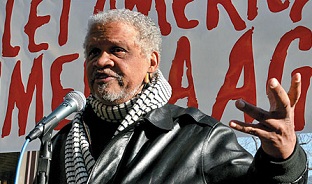

De Afro-Amerikaanse dichter, schrijver en essayist Ishmael Scott Reed werd geboren op 22 februari 1938 in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Zie ook alle tags voor Ishmael Reed op dit blog.

Chattanooga

1

Some say that Chattanooga is the

Old name for Lookout Mountain

To others it is an uncouth name

Used only by the uncivilised

Our a-historical period sees it

As merely a town in Tennessee

To old timers of the Volunteer State

Chattanooga is “The Pittsburgh of

The South”

According to the Cherokee

Chattanooga is a rock that

Comes to a point

They’re all right

Chattanooga is something you

Can have anyway you want it

The summit of what you are

I’ve paid my fare on that

Mountain Incline #2, Chattanooga

I want my ride up

I want Chattanooga

2

Like Nickajack a plucky Blood

I’ve escaped my battle near

Clover Bottom, braved the

Jolly Roger raising pirates

Had my near miss at Moccasin Bend

To reach your summit so

Give into me Chattanooga

I’ve dodged the Grey Confederate sharpshooters

Escaped my brother’s tomahawks with only

Some minor burns

Traversed a Chickamauga of my own

Making, so

You belong to me Chattanooga

De Vlaamse dichter en schrijver Paul van Ostaijen werd geboren in Antwerpen op 22 februari 1896. Zie ook alle tags voor Paul van Ostaijen op dit blog.

Het stille lied

Voor de zoveelste maal heb ik Botticelli over het land zien gaan,

die bloemen zaait.

En weer strekken de bomen hun geweldig bottende takken,

levensdrift die de Japannezen begrepen.

De avond weerhoudt zich te vallen, de mensen haasten zich in dit jong getij,

arme schelpvissers met de wilde hoop:

thans zal de vloed hun rijkdom zijn.

De huizenvlakten en toonprojecties, die zijn de afstand tussen hen en mij,

verdringen mij naar ’t diepst van mijn geweten.

Doch niet meer een roes is thans de Lente die van mij gaat,

niet meer het zwak geloof: dit is zich geven.

Mocht het mij thans worden het bruidsgetij der wijze maagden;

God in mij moet wekken, – Jezus en Lazarus tevens, –

moesten ook mijn nagels in mijn vlees de vreselikste beproeving enten:

de snik, het ‘alles is volbracht’ en de drie-dagen-dood.

Nog niet heb ik het leed, het grote godsgeschenk begrepen.

Nog sta ik dwaas vóór al de wonderen en ben nog steeds mijn eigen deemoed zoekend,

die mij de sleutel geven moet.

Thans zal ik enkel daarvoor zorgen:

olie te hebben ten allen tijde, want wanneer de bruidegom komt weet geen.

Eenieder hoeft gereed te zijn,

want plots kunnen lichten de schaduwen van de bomen doen zinken,

dan is de bruidegom dichtbij.

Hij die de bruidegom van het Leven vóór de poort laat staan,

zal blijven onbevrucht een ganse leven.

Doch hij, – o mocht ik reeds een ver Hosannah horen! –

die olie had, de bruidegom zal in hem de lichten omzetten

en hij zal zijn hooglied mogen zingen, de klare stem van God.

Dit lied dat staan zal in de werkelijkheid der dingen

als de gebeurtenis van een ruimere Lente, na de hopeloze wentelingen van een lange jarenreeks.

De Britse schrijver Philip Ballantyne Kerr werd geboren in Edinburgh op 22 februari 1956. Zie ook alle tags voor Philip Kerr op dit blog.

Uit: Prussian Blue

“October 1956

It was the end of the season and most of the hotels on the Riviera, including the Grand Hotel Cap Ferrat, where I worked, were already closed for the winter. Not that winter meant much in that part of the world. Not like in Berlin, where winter is more a rite of passage than a season: you’re not a true Berliner until you’ve survived the bitter experience of an interminable Prussian winter; that famous dancing bear you see on the city’s coat of arms is just trying to keep himself warm.

The Hotel Ruhl was normally one of the last hotels in Nice to close because it had a casino and people like to gamble whatever the weather. Maybe they should have opened a casino in the nearby Hotel Negresco-which the Ruhl resembled, except that the Negresco was closed and looked as if it might stay that way the following year. Some said they were going to turn it into apartments but the Negresco concierge-who was an acquaintance of mine, and a fearful snob-said the place had been sold to the daughter of a Breton butcher, and he wasn’t usually wrong about these things. He was off to Bern for the winter and probably wouldn’t be back. I was going to miss him but as I parked my car and crossed the Promenade des Anglais to the Hotel Ruhl I really wasn’t thinking about that. Perhaps it was the cold night air and the barman’s surplus ice cubes in the gutter but instead I was thinking about Germany. Or perhaps it was the sight of the two crew-cut golems standing outside the hotel’s grand Mediterranean entrance, eating ice cream cones and wearing thick East German suits of the kind that are mass-produced like tractor parts and shovels. Just seeing those two thugs ought to have put me on my guard but I had something important on my mind; I was looking forward to meeting my wife, Elisabeth, who, out of the blue, had sent me a letter inviting me to dinner. We were separated, and she was living back in Berlin, but Elisabeth’s handwritten letter-she had beautiful SŸtterlin handwriting (banned by the Nazis)-spoke of her having come into a bit of money, which just might have explained how she could afford to be back on the Riviera and staying at the Ruhl, which is almost as expensive as the Angleterre or the Westminster. Either way I was looking forward to seeing her again with the blind faith of one who hoped reconciliation was on the cards. I’d already planned the short but graceful speech of forgiveness I was going to make. How much I missed her and thought we could still make a go of it-that kind of thing. Of course, a part of me was also braced for the possibility she might be there to tell me she’d met someone else and wanted a divorce. Still, it seemed like a lot of trouble to go to-it wasn’t easy to travel from Berlin these days.”

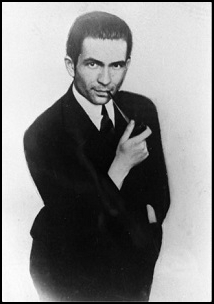

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Hugo Ball werd geboren op 22 februari 1886 in Pirmasens. Zie ook alle tags voor Hugo Ball op dit blog.

Der Verzückte

Und manchmal überfällt mich eine tolle Seligkeit.

Alle Dinge tragen den Orchideenmantel der Herrlichkeit.

Alle Gesichte tragen an goldenen Stäben zur Schau ihr innerstes Wesen.

Die Inschriften der Natur fangen zu stammeln an, leicht zu lesen.

Alle Wunder drängen wie Seesterne an die Oberfläche.

Die Golfströme der Luft kreisen und schweben wie diamantene Bäche.

Aus jedem toten Gerät wollen sich hundert staunende Augen erheben.

In jedem Stein überschlägt sich wild eifersüchtiges Leben.

Die Kirchtürme flammende Gottesschwerter. Dröhnend schlagen die Stunden.

Meine Zunge eine Jerichorose. Duft strömt und Musik mir vom Munde.

Auf meine Fingerspitzen, die sich in Beschwörungen ducken,

Lassen sich alle verirrten Küsse nieder, die durch das Weltall zucken.

Daher begibt es sich, daß über den fliegenden Dächern der Stadt,

Die mich beherbergt, der leuchtende Mond seinen Bogen hat

Wie aus Opal geschnitten ein weitgespannter Viadukt,

Und daß nicht mehr Wirklichkeit ist, was da spukt.

Es sind geisterhafte Orchester auf der Wanderung zu vernehmen.

Es ist, als ob unterm Pflaster Höllen aus Licht heraufgeschwommen kämen.

Die Menschen, die da gehen, schreiten an elfenbeinernen Stöcken.

Die Häuser, die da stehen, prunken in Purpurmänteln und Galaröcken.

Die Bilder und die Gesichte kommen hervor wie trunkene Tropenfalter,

Wenn du in roten Nächten durch die Glutgärten Ceylons gehst.

An Ärmel und Kniee hangen sich ihrer so viele und schwer,

Daß du ermattet zuletzt, ganz wirr und taumelnd im blühenden Gifte stehst.

Cover

De Servische schrijver Danilo Kiš werd geboren op 22 febrari 1935 in Subotica. Zie ook alle tags voor Danilo Kiš op dit blog.

Uit: Kinderleed (Het spelletje, vertaald door Reina Dokter en Lela Zečković)

“De man gluurde door het sleutelgat en dacht Dat kan toch niet waar zijn; dat is Andreas niet. Nog een hele tijd bleef hij zo gebukt staan en dacht: Nee, dat is onze Andreas niet. Hij bleef zo staan, roerloos, zelfs toen hij er pijn in zijn rug van kreeg. Hij was vrij lang en het slot zat ongeveer ter hoogte van zijn dijen. Toch verroerde hij zich niet. Ook niet toen zijn ogen achter zijn brilleglazen begonnen te tranen, waardoor hij even alles wazig zag. Door het sleutelgat stroomde koude lucht als door een tochtige gang. Maar hij hield vol. Alleen toen hij op een gegeven moment met zijn bril tegen het slot stootte, trok hij heel even zijn hoofd terug. Dat moet ik aan Maria laten zien, dacht hij met enig leedvermaak, zich nauwelijks bewust van die gedachte, en ook niet van het leedvermaak dat erachter school. Ik moet Max Ahasverus, de koopman in ganzeveren, aan Maria laten zien. Hij wist zelf niet waarom, maar hij had de behoefte haar te kwetsen. En dit zal haar kwetsen, dacht hij niet zonder plezier. Ik moet haar laten zien hoe de onderaardse rivieren van het bloed stromen. En dat Andreas niet haar Blonde Jongetje is (zoals zij denkt), maar zijn vlees en bloed, de kleinzoon van Wandelende Max. En dat zal haar pijn doen. Hier had je een bewijs dat hij gelijk had, en hij genoot nu al van haar stille leed en haar onmacht om zich, gehuld in opstandig zwijgen, te verzetten tegen de kracht van zijn argumenten als ze zag (als hij haar laat zien) hoe haar Blonde Jongetje, haar Andreas, langs zijn klanten gaat en van het ene schilderij naar het andere loopt, alsof hij door de eeuwen wandelt. En dat zal haar pijn doen. Daarom wou hij niet weg van het sleutelgat, daarom stelde hij het moment van de te behalen overwinning uit dat zo maar binnen handbereik lag. Eigenlijk wou hij niet, hij kon niet zijn hand uitstrekken en die kans grijpen om haar te kwellen. Daarom stelde hij dat ogenblik uit. Hij wachtte tot het vanzelf zou rijpen, in de modder zou vallen als een rijpe pruim. Daarom wou hij Maria niet meteen roepen, en bleef almaar door het sleutelgat kijken, waar als door een tochtige gang koude lucht doorkwam, ergens uit de verte, waar geen tijd bestaat.”

De Ierse schrijver Sean O’Faolain werd geboren op 22 februari 1900 in Cork. Zie ook alle tags voor Sean O’Faolain op dit blog.

Uit: Vive Moi!

‘The immeasureable difference between that summer school and any other place of study I have ever been in was that it was voluntary. We wanted – and how eagerly! – to be able to speak Irish well and fluently, not just as a useful accomplishment but because Irish was a symbol of the larger freedom to which we were all groping…. So when we spoke Irish we simply evoked another country, another life, another people. Mountains were mountains, roads were roads, and glens (always Scottish); but when, for these things, we uttered the Irish words sleibhthe, boithre, and gleannta we spoke passwords to another world. Irish became our Runic language. It made us comrades in a secret society. We sought and made friendships, some of them to last forever like conspirators, in a state of high exaltation, merely by using Irish words.’

(…)

His Majesty’s Commissioners of Education had taken every precaution to keep from us the bitter, ancient memoiries of our race. From various unguarded sources the ancient memories nevertheless escaped through – a a prhase, or a word from a theach, or no more than a inflection in his voice, or in an uncensored passage in a history book about the bravery of Irish soldiers in the jacobite or European wars, until, drop by drop, the well-springs of my being became brimful, and finally, when I was sixteen, which was the year of 1916 and the last Irish Rebellion, it burst in a fountaining image of the courage of man. … If I say a final no to that school, what I am really saying, then, is a no to that Ireland. I am saying no to my own pyhood, my own youth, even to my own parents, to everything that, had I not rebelled against it, would have mismade me for life.’

(…)

‘I was the mad mole who thought he had made Mont Blanc. I was the mouse in the wainscotting of the Vatican who believed that he told the Pope every night what His Holiness must tell the world every morning. I was Ireland, the guardian of her faith, the one solitary man who would keep the Republican symbol alive, keep the last lamp glowing before the last icon, even if everybody else denied or forgot the gospel that had inspired us all from 1916 onwards. I firmly believed in the dogma that had by now become the last redoubt of the minority’s resistance to the majority; that the people have no right to do wrong. Like all idealists, I was fast becoming heartless, humourless and pitiless.’

Cork

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 22e februari ook mijn blog van 22 februari 2018 en ook mijn blog van 22 februari 2015 deel 1 en ook deel 2.