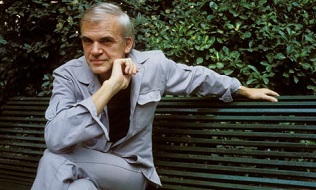

De Tsjechische schrijver Milan Kundera werd geboren in Brno op 1 april 1929. Zie ook alle tags voor Milan Kundera op dit blog.

Uit: Ignorance

“The Greek word for “return” is nostos. Algos means “suffering.” So nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return. To express that fundamental notion most Europeans can utilize a word derived from the Greek (nostalgia, nostalgie) as well as other words with roots in their national languages: añoranza, say the Spaniards; saudade, say the Portuguese. In each language these words have a different semantic nuance. Often they mean only the sadness caused by the impossibility of returning to one’s country: a longing for country, for home. What in English is called “homesickness.” Or in German: Heimweh. In Dutch: heimwee. But this reduces that great notion to just its spatial element. One of the oldest European languages, Icelandic (like English) makes a distinction between two terms: söknuour: nostalgia in its general sense; and heimprá: longing for the homeland. Czechs have the Greek-derived nostalgie as well as their own noun, stesk, and their own verb; the most moving, Czech expression of love: styska se mi po tobe (“I yearn for you,” “I’m nostalgic for you”; “I cannot bear the pain of your absence”). In Spanish añoranza comes from the verb añorar (to feel nostalgia), which comes from the Catalan enyorar, itself derived from the Latin word ignorare (to be unaware of, not know, not experience; to lack or miss), In that etymological light nostalgia seems something like the pain of ignorance, of not knowing. You are far away, and I don’t know what has become of you. My country is far away, and I don’t know what is happening there. Certain languages have problems with nostalgia: the French can only express it by the noun from the Greek root, and have no verb for it; they can say Je m’ennuie de toi (I miss you), but the word s’ennuyer is weak, cold — anyhow too light for so grave a feeling. The Germans rarely use the Greek-derived term Nostalgie, and tend to say Sehnsucht in speaking of the desire for an absent thing. But Sehnsucht can refer both to something that has existed and to something that has never existed (a new adventure), and therefore it does not necessarily imply the nostos idea; to include in Sehnsucht the obsession with returning would require adding a complementary phrase: Sehnsucht nach der Vergangenheit, nach der verlorenen Kindheit, nach der ersten Liebe (longing for the past, for lost childhood, for a first love).

Milan Kundera (Brno, 1 april 1929)