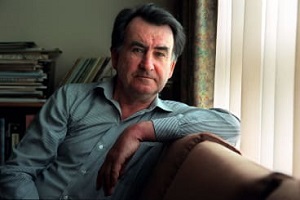

De Australische schrijver Gerald Murnane werd geboren op 25 februari 1939 in Coburg, Victoria, een voorstad van Melbourne, en heeft de staat Victoria bijna nooit verlaten. Delen van zijn jeugd werden doorgebracht in Bendigo en de Western District. In 1956 studeerde hij af aan het De La Salle College in Malvern. Murnane studeerde daarna kort voor het rooms-katholieke priesterschap. Hij verliet dit pad echter en werd leraar op basisscholen (van 1960 tot 1968) en in de Apprentice Jockeys ‘School van de Victoria Racing Club. Hij behaalde in 1969 een Bachelor of Arts aan de University of Melbourne en werkte vervolgens tot 1973 in de Victorian Education Department. Vanaf 1980 begon hij creatief schrijven te doceren aan verschillende instellingen voor hoger onderwijs. De eerste twee boeken van Murnane, “Tamarisk Row” (1974) en “A Lifetime on Clouds” (1976), lijken semi-autobiografische verslagen te zijn van zijn kindertijd en adolescentie. Beide zijn grotendeels samengesteld uit zeer lange maar grammaticale zinnen. In 1982 bereikte hij zijn volwassen stijl met “The Plains”, een korte roman over een naamloze filmmaker die naar ‘Inner Australia’ reist, waar hij de vlaktes probeert te filmen onder het beschermheerschap van rijke landeigenaren. “The Plains” werd gevolgd door: “Landscape With Landscape” (1985), “Inland” (1988), “Velvet Waters” (1990) en “Emerald Blue” (1995). Een essaybundel, “Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs”, verscheen in 2005. Deze boeken houden zich allemaal bezig met de relatie tussen geheugen, beeld en landschap, en vaak met de relatie tussen fictie en non-fictie. In 2009 verscheen, na meer dan een decennium, pas weer opnieuw fictioneel werk van Murnane: “Barley Patch”, gevolgd door “A History of Books” in 2012 en “A Million Windows” in 2014.

Uit: Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs

“On the road to Bendigo: Kerouac’s Australian life

Like other children of my time and place, I watched films from Hollywood in the first years after World War II, although I believe I watched fewer than most children. I watched perhaps twenty double-feature programs from 1946 to 1948. The films were mostly cowboy films, in black and white, and I watched them on Saturday afternoons in the Lyric Theatre, Bendigo, of which I remember only that the floor was quite level, so that the screen always seemed high above me and remote. The films I watched made me discontented. Scene after scene disappeared from the screen before I had properly appreciated it; the characters moved and spoke much too fast. I hardly ever got the hang of a film, as my brother would say afterwards when I asked him to explain what I had missed. What I looked for in films was what I called pure scenery. I thought of pure scenery as the places safely behind the action: the places where nothing seemed to happen. Occasionally I glimpsed the kind of scenery I wanted. Behind the men on horses or the encampment of wagons was a broad tract of tall grass leading back to a line of hills. When I saw any such banal arrangement of grassy middle distance and hilly background, I tried to do to it something for which the simplest word I could have found was swallow. I wanted to feel that waving grass and that line of hills somewhere inside me. I wanted grass and hills fixed inside the space that began, as I thought, behind my eyes. I was not so literal-minded that I was troubled by cartoon images of a greedy boy with his cheeks swollen by a segment of landscape-pie. Yet the word swallow was not inapt. Getting the scenery from outside to inside seemed to engage me in some kind of bodily effort. And if I did not actually think of mouth or stomach, I could still see myself crouching over scenery made somehow conve-niently tiny; the scenery brought so close to my face that the familiar became blurred, and strange details filled my eyes; some crucial moment arriving for which I had no words; and finally the scenery safely mine, a piece of plain with a rim of hills floating inside my private space, and rather higher than lower, as though my space was a sort of appropriate that an early Australian poet should have put on racing silks and ridden at Flemington and Coleraine. The racecourse must have seemed sometimes to Gordon his landscape of last resort. A man who had been born in Ballarat in the 1890s once told me that he had heard from a former jockey who rode with Gordon. At the barrier before a steeplechase one day at Dowling Forest, Gordon announced that this would be his last race. When he urged his horse like a madman at the first jump, the other riders knew what he had meant. That was the last they saw of him — in racing parlance. He won that day by a great space.

Gerald Murnane (Coburg, 25 februari 1939)