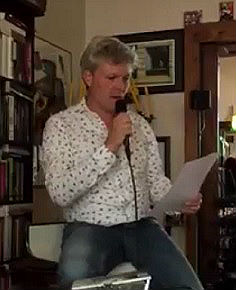

De Nederlandse dichter Hanz Mirck werd geboren op 8 april 1970 te Zutphen. Zie ook alle tags voor Hanz Mirck op dit blog.

Hospice

Je bent hier alleen gekomen, al waren er mensen bij je

Je moet het zelf doen en toch helpen we je. Vanaf hier

heeft de poortersklok een andere klank, een andere glans,

langer, ijler in de ijzige wind, langzaam wordt het winter,

het licht draalt over de glanzende straten. Laat je drijven

over de IJssel, langzaam laten onze handen je gaan

Zie hoe nietig de torens, twijfel niet langer aan wat je al

zo lang zeker weet. Ga nu maar, zie hoe onbeduidend

van bovenaf de stad, zie de kleuren vervagen, hoe koud

en grauw de lucht, grijs de daken en het water, het laatste

licht glanst nog één keer in de gouden bol op de Walburgkerk,

de winkelketens die de vrijhandel zullen vermalen,

de banken waar men voor wisselgeld moet betalen

en dit hospice in een ontwijde kerk, waar we de dood nu

anders zien, weerspiegeld in het water, onze handen leeg,

het grote geduld in de ruimte boven ons – wachtend

Ooit 2

Wie moet haar nu voorlezen

doen vergeten dat ze niet slapen kan

Wie moet naar haar kijken als ze elders is

bedenken waar ze zich om omdraait

Nu ik mijn angst om haar

te verliezen ben verloren

Nu ik haar niet meer in mijn dromen

hoef te zoeken, waar ben je toch?

Ga nu maar slapen; zo alleen

kan iemand je wakker kussen

het glas om je breken

de lucht om je in beweging brengen.

Liedje voor morgen

Een prijs, iemand zei het, ver weg, en toch klonk het dichtbij,

dichtbij je oor. Een prijs waarvan je nog nooit had gehoord

Het was gezegd voor je het wist. Nu weet je het niet meer zeker

Jij? Een prijs? Een gedicht waar een prijs is uitgehaald en

weer in is terug gezet. Je bent dezelfde als voor de prijs, toch

is er iets anders. Naar wie de prijs genoemd is ken je niet

Tot elkaar gebracht als twee mensen op eenzelfde perron,

in een denderende trein in de nacht, naar jouw huis. Onverwacht

Laat, maar eerder dan je dacht. Je schrikt op van je eigen

gezicht in het raam, ben je dat echt? Die winnaar?

De wereld is hetzelfde en toch anders, de wereld

is de helft van de tijd donker, een sein glijdt soepel

van rood op groen. Je bent op de goede weg, lijkt het wel,

het donker lijkt anders. Morgen weet je het zeker, zul je zingen.

Hanz Mirck (Zutphen, 8 april 1970)

De Duitse schrijver, essayist en vertaler Christoph Hein werd geboren op 8 april 1944 in Heinzendorf in Silezié. Zie ook alle tags voor Christian Hein op dit blog.

Uit: Gegenlauschangriff – Anekdoten aus dem letzten deutsch-deutschen Kriege

„Anfang der 80er Jahre des vergangenen Jahrhunderts, gegen Ende des letzten deutsch-deutschen Krieges, der seinerzeit als kalter geführt wurde, erhielt das Ensemble des Maxim Gorki Theaters in Ostberlin vom Düsseldorfer Intendanten die Einladung, mit seiner gerühmten Aufführung der Drei Schwestern von Anton Tschechow im Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus zu gastieren, also mit jenem Stück, in dem die Schwestern Olga, Mascha und Irina in einer provinziellen Gouvernementsstadt verkümmern und lebenslang davon träumen, nach Moskau zu reisen. »Nach Moskau, nach Moskau!« Es wurden drei Aufführungen innerhalb von vier Tagen vereinbart, der dritte Abend sollte spielfrei bleiben. Ein Jahr nach diesem Gastspiel hatte eines meiner Stücke eine Uraufführung am Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, und meine Obrigkeit gestattete mir diesmal überraschend, das Land zu verlassen und nach Düsseldorf zur Premiere zu fahren. Bei einem Essen mit dem Chefdramaturgen des Theaters berichtete dieser von dem vorjährigen Gastspiel der Drei Schwestern, die Aufführung sei ein großer Erfolg gewesen. Am allerersten Tag, eine Stunde nach Ankunft der Ostberliner Schauspieler, sei die Darstellerin von Olga, der ältesten Schwester, in seinem Büro erschienen und habe ihn unter vier Augen gefragt, ob es eine Möglichkeit gebe, an dem dritten, dem spielfreien Tag nach Paris zu fahren, ohne an der Grenze einen Pass vorweisen zu müssen. An der Grenze zwischen Frankreich und der Bundesrepublik gab es zu jener Zeit noch immer, wenn auch sehr zwanglos, Ausweiskontrollen. Die Schauspielerin fürchtete, einem französischen Grenzer ihren Pass vorlegen zu müssen und von ihm einen Einreisestempel zu bekommen, den sie dann später bei der Heimreise zu erklären hätte.“

Christoph Hein (Heinzendorf, 8 april 1944)

De Nederlandse schrijfster en journaliste Judith Koelemeijer werd geboren in Zaandam op 8 april 1967. Zie ook alle tags voor Judith Koelemeijer op dit blog.

Uit: Het zwijgen van Maria Zachea – Een ware familiegeschiedenis

“Het was een onzinnig idee, al had ze dat niet zo tegen Lucie gezegd.

‘Moe heeft heimwee, Jo’, vertelde haar zus die ochtend door de telefoon. ‘Ze moet zo snel mogelijk naar huis.’

‘Naar huis?!’, had ze uitgeroepen.

‘Ja, het gaat niet goed met haar in het ziekenhuis.’

‘Maar wat moet ze thuis doen?’

Hun moeder had een paar weken eerder, op 29 december 1988, een hersenbloeding gehad. Ze was nog niet hersteld van de operatie, ze kon amper op haar benen staan.

‘Moe vindt het niks om zo lang van huis te zijn’, zei Lucie.

‘En wat zegt de dokter ervan?’

‘De specialist wil haar aan het infuus leggen omdat ze ’t verdomt om te eten …’

‘Nou dat bedoel ik!’

‘… en daar zijn wij het helemaal niet mee eens.’

Dat moest er nog bij komen. Misschien was zij behoudender in die dingen, ze was tenslotte zeventien jaar ouder dan Lucie. Maar het was toch raar om tegen het advies van de dokter in te gaan.

‘Jullie lopen véél te hard van stapel’, zei ze. ‘Kunnen jullie niet wachten tot ze is opgeknapt?’

Maar volgens Lucie ging moe alleen maar achteruit. Ook dat verbaasde Jo. De hersenoperatie was niet goed gelukt, dat wist ze. De chirurg had gesproken over verkalking, complicaties, een bloedvat dat hij slechts ‘provisorisch’ had kunnen dichten. Maar moe was toch niet opgegeven? Een paar dagen eerder had ze van de fysiotherapeut nog een rek gekregen, zodat ze kon oefenen met lopen.

‘Ik neem het niet voor mijn verantwoording’, zei ze. ‘Moe is tachtig. Zo’n oude, zieke vrouw hoort in het ziekenhuis. En wie gaat er thuis voor moe zorgen? Jij soms?’

‘Maak je geen zorgen, Jo’, zei Lucie. ‘Dat regelen we wel. En het is toch maar voor een paar maanden. Volgens de dokter is moe terminaal.’

Het duizelde haar na het telefoongesprek. De afgelopen weken waren al zo chaotisch verlopen. En nu kwam Lucie met dit idiote voorstel. Wat was er toch met moe? Ze was altijd een gezonde, ferme vrouw geweest, die niet hield van zeuren of moeilijk doen. Maar sinds ze in het ziekenhuis lag, wilde ze niks meer.”

Judith Koelemeijer (Zaandam, 8 april 1967)

De Afrikaanse-Amerikaanse schrijfster Nnedi Okorafor werd geboren op 8 april 1974 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Zie ook alle tags voor Nnedi Okorafor op dit blog.

Uit: Hello, Moto

“With the wig finally off, Coco and Philo felt more distant to me. Thank God.

Even so, because it was sitting beside me, I could still see them. Clearly. In my head. Don’t ever mix juju with technology. There is witchcraft in science and a science to witchcraft. Both will conspire against you eventually. I realized that now. I had to work fast.

It was just after dawn. The sky was heating up. I’d sneaked out of the compound while my boyfriend still slept. Even the house girl who always woke up early was not up yet. I hid behind the hedge of colorful pink and yellow lilies in the front. I needed to be around vibrant natural life, I needed to smell its scent. The flowers’ shape reminded me of what my real hair would look like if the wig hadn’t burned it off.

I opened my laptop and set it in the dirt. I put my wig beside it. It was jet black, shiny, the “hairs” straight and long like a mermaid’s. The hair on my head was less than a millimeter long; shorter than a man’s and far more damaged. For a moment, as I looked at my wig, it flickered its electric blue. I could hear it whispering to me. It wanted me to put it back on. I ran my hand over my sore head. Then I quickly tore my eyes from the wig and plugged in the flash drive. As I waited, I brought out a small sack and reached in. I sprinkled cowry shells, alligator pepper and blue beads around the machine for protection. I wasn’t taking chances.

I sat down, placed my fingers on the keyboard, shut my eyes and prayed to the God I didn’t believe in. After all that had happened, who would believe in God? Philo had been in Jos when the riots happened. I knew it was her and her wig. A technology I had created. Neurotransmitters, mobile phones, incantation, and hypnosis- even I knew my creation was genius. But all it sparked in the North was death and mayhem. During the riots there, some men had even burned a woman and her baby to death. A woman and her baby!

I didn’t want to think of what Philo gained after causing it all. She never said a word to me about it. However, soon after, she went on a three-day shopping spree in Paris. We could leave Nigeria, but never for more than a few days.”

Nnedi Okorafor (Cincinnati, 8 april 1974)

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Barbara Kingsolver werd geboren op 8 april 1955 in Annapolis, Maryland. Zie ook alle tags voor Barbara Kingsolver op dit blog.

Uit: Unsheltered

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.”

She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words.

“It’s not a living thing. You don’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?”

“Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Again the roar on her eardrums. She stared at the man’s black coveralls, netted with cobwebs he’d collected in the crawl space. Petrofaccio was his name. Pete. “How could a house this old have a nonexistent foundation?”

“Not the entire house. You see where they put on this addition? Those walls have nothing substantial to rest on. And the addition entails your kitchen, your bathrooms, everything you basically need in a functional house.”

Includes, she thought. Entails is the wrong word.

One of the neighbor kids slid out his back door. His glance hit Willa and bounced off quickly as he cut through the maze of cars in his yard and headed out to the alley. He and his brother worked on the vehicles mostly at night, sliding tools back and forth under portable utility lights. Their quiet banter and intermittent Spanish expletives of frustration or success drifted through Willa’s bedroom windows as the night music of a new town. She had no hard feelings toward the vehicle bone yard, or these handsome boys and their friends who all wore athletic shorts and plastic bath shoes as if life began in a locker room. The wrong here was a death sentence falling on her house while that one stood by, nonchalant, with its swaybacked roofline and vinyl siding peeling off in leprous shreds. Willa’s house was brick. Not straw or sticks, not a thing to get blown away in a puff.”

Barbara Kingsolver (Annapolis, 8 april 1955)

Cover

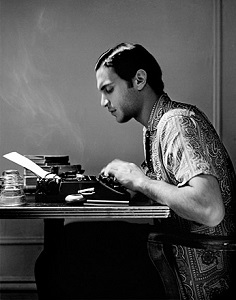

De Amerikaanse schrijver John Fante werd geboren in Colorado op 8 april 1909. Zie ook alle tags voor John Fante op dit blog.

Uit: The Brotherhood of the Grape

“The only change in the Cafe Roma in over a quarter of a century was the clientele. The old men I remembered were planted in the graveyard, replaced by a new generation of old men. Otherwise things were as usual. The long mahogany bar was the same and so were the two dusty, flyspecked Italian and American flags above it. A touch of the modern was displayed above the bar, a blowup of Marlon Brando as the Godfather, four feet square, in a frame of gold filigree. The same propeller fan droned from the ceiling, spinning slowly enough not to disturb the warm air, with sportive flies landing on the propeller blades, enjoying a spin or two, then jumping off. Green shades over the front windows gave the dark interior an illusion of coolness, as did the fragrance of tap beer. But this aroma was knifed by the gut-slashing pungency of olive oil and rancid parmigiano cheese mixed with the piny tang of fresh sawdust deep on the floor. Something else had changed: when I was a lad the patrons of the Cafe Roma spoke only Italian. Now the new breed of old cockers spoke English, the English of the street, but English all the same. Eight or nine of them were crowded around a green felt table in the rear. The low-hanging lamp lit up five card players seated around the table, the others standing about, watching and kibitzing. My father was one of the spectators. They were a cranky, irascible, bitter gang of Social Security guys, intense, snarling, rather mean old bastards, bitter, but enjoying their cruel wit, their profanity and their companionship. No philosophers here, no aged oracles speaking from the depths of life’s experience. Simply old men killing time, waiting for the clock to run down. My father was one of them. It came to me as a shock. I never thought of him that way until I saw him with his own kind. Now he looked even older than the gaffers around him. I moved to Papa’s side and said ‘Hi.’ He grunted. The bald-headed dealer never took his eyes off the cards as he spoke to my father. `Friend of yours, Nick?’ `Nah. This is my kid Henry.’ I recognized the dealer: Joe Zarlingo, a retired railroad engineer. Though he had not operated a train in ten years, he still wore striped overalls and an engineer’s cap and sported all manner of colored pens and pencils in his bib pocket, as if serving notice that he was a very busy man.

I looked around and said ‘Hello’ to everybody, and two or three answered with preoccupied growls, not bothering to look at me. Some I remembered. Lou Cavallaro, a retired brakeman. Bosco Antrilli, once the super at the telegraph office, the father of Nellie Antrilli, whom I seduced on an anthill in a field south of town in the dead of night (the anthill unseen, Nellie and I fully clothed, then screaming and tearing off our clothes as the outraged ants attacked us). Pete Benedetti, formerly postmaster.”

John Fante (8 april 1909 – 8 mei 1983)

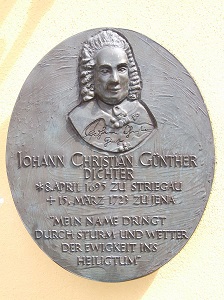

De Duitse dichter Johann Christian Günther werd geboren op 8 april 1695 in Striegau. Zie ook mijn blog van 8 april 2007. Zie ook alle tags voor Johann Christian Günther op dit blog.

Ich will lachen, ich will scherze

Ich will lachen, ich will scherzen,

Ob es gleich den Neid verdreust,

Andre mögen Grillen fangen,

Nichts ermuntert mein Verlangen,

Nichts bekümmert meinen Geist

Als der Wechsel treuer Herzen.

Eilt man nicht in Rosenbrechen,

Lauft der Vortheil aus der Hand;

In der Jugend Frühlingsjahren

Steckt der Kram verliebter Wahren,

Aber auch der Unbestand.

Brecht, eh Reu und Dörner stechen!

Eh noch Glut und Kraft verrauchen,

Trägt der Kuß Zufriedenheit;

Heute lebt man ohne Sorgen,

Gott und Vorsicht weis, ob morgen;

Ey, so lerne man der Zeit

Bey Gesellschaft recht gebrauchen.

Ohne Lieben ist das Glücke

Hier auf Erden nichts als Dunst;

Reichthum kan den Gram nicht lindern,

Ehre kan den Schmerz nicht mindern,

Nur die Liebe kan die Kunst.

Eitle Wüntsche, bleibt zurücke!

Aus der Liebe quillt Vergnügen

Und der Nachschmack güldner Zeit;

Ein galant und treu Gemüthe

Reizt uns nebst der Schönheit Blüthe,

Bis die Wollust Flammen streut.

Ach, mein Herz, halt dies verschwiegen!

In des Mundes Purpurhöhlen

Nimmt der Kuß noch größre Kraft.

Von dem Warthen wächst der Zunder,

O wie viel Entzückungswunder

Nähren nicht die Leidenschaft

Gleich und klug verliebter Seelen.

Rühmt mir auch nicht blos das Prangen

Einer Haut, die auswärts gleißt!

In den Farben ohne Leben

Find ich lauter Eckel kleben;

Find ich aber Wiz und Geist,

Ey, so bin ich gleich gefangen.

Es erwehlt mein Herz zwo Lippen,

Nur es hält sich annoch still;

Bergt ihrs auch, ihr losen Augen,

Euer stetig Feuersaugen

Redet so bereits zu viel.

Grade zu stößt oft an Klippen.

Johann Christian Günther (8 april 1695 – 15 maart 1723)

Gedenkplaat in Königswinter

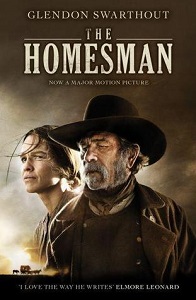

De Amerikaanse schrijver Glendon Fred Swarthout werd geboren op 8 april 1818 in Pinckney, Michigan. Zie ook alle tags voor Glendon Swarthout op dit blog.

Uit: De homesman (Vertaald door Jan Willem Reitsma)

“Aan het eind van de zomer zei Line tegen hem dat ze twee maanden op streek was. Nog een mondje om te voeden. En trouwens, zei ze, drieënveertig was te oud. Ze zei dat het kind een waterhoofd zou hebben, helemaal kreupel zou zijn of vervloekt met een hazenlip, want God was vast boos op ze. Kijk maar wat er dit jaar allemaal was gebeurd.

In het voorjaar waren ze alle koeien, op één koe en haar kalf na, aan boutvuur kwijtgeraakt.

Tegelijkertijd was Virgil van zestien, hun enige zoon en een echte mannetjesputter, ervandoor gegaan om in Californië naar pyriet te graven.

In juli hadden hagelbuien hun tarwe platgeslagen en toen in augustus de maïs rijpte, hadden helse winden die in twee weken voor zo’n groot deel verschroeid dat ze de armzalige kolven in het najaar met de hand hadden geplukt en gepeld in plaats van ze helemaal naar de molen te rijden. Acht hectare tarwe en twaalf hectare maïs waren weggevaagd. Oogsten die geld moesten opleveren. God beschikte over het weer, zei Vester.

Nu was het maart en Line bleef hun ellende opsommen zoals een kind een gedicht zou voordragen. Hij hoorde haar aan, want ze zei de laatste tijd nog maar zelden iets en misschien hielp het tegen wat het ook was dat haar mankeerde.

Voordat de eerste sneeuw gevallen was, toen ze wisten dat het erom zou gaan spannen of ze de hele winter te eten zouden hebben, stuurden ze Loney, hun oudste dochter, naar een familie veertien mijl verderop, waar ze veel beter af was. Sloven voor een derde van een bed plus kost en inwoning, het arme kind.

Toen kreeg een van hun ossen horzellarven – maden onder de huid. Je kon de zwelling opensnijden en de maden met petroleum bevochtigen om ze dood te maken, als je tenminste petroleum had. Als je niets deed, zogen de maden de ziel uit je os, dat wist Line zeker, en als hij dit voorjaar voor de ploeg werd gezet, zou hij daar op de akker neervallen, het arme beest.

Daarna deze winter der verdoemenis. Voor welke zonde boetten ze? Het was zo koud dat het hout en de maïskolven al in januari op waren en ze strovlechten moesten stoken en daarop koken.”

Glendon Swarthout (8 april 1918 – 23 september 1992)

Cover

De Duitse schrijver Martin Grzimek werd geboren op 8 april 1950 in Trutzhain, Hessen. Zie ook alle tags voor Martin Grzimek op dit blog.

Uit: Shadowlife (Die Beschattung, vertaald door Breon Mitchell)

“When he was finished he handed me a small cordless microphone Now hide this here in the room, while I’m concealing this somewhat larger one somewhere in the bathroom. When we’re finished we’ll pretend we’re children. You look for mine and I’ll look for yours. Whoever finds the other’s first wins.” Of course he won. Not more than a minute had passed before he was standing in the bathroom door: You made it much too easy for me.” I looked for fifteen minutes before I accidentally felt the little button on the inner edge of the shower curtain. “lour thinking’s too complicated,” he said, and took his leave. Nk a practiced every evening for an hour. I came to know each detail of my apartment, every object, every cavity, every protrusion. I never matched my teacher’s speed in hiding things and finding them, but I didn’t lag far behind. On his final visit he asked if he could kiss me on the cheek. Then he told me what a quick learner I was, and before leaving, added: “You were a good student. I want to give you some advice. Imagine that you want to keep something to yourself—a word, a name, an observation. Use Your mind to do it. That’s the best hiding place there is. Never NVrite anything down. Never hide a note that’s meant to be secret. You’ve learned that nothing is ever so well hidden it can’t be found. And if you write down a word, a number, or a code, your thoughts are in a material form; they can be used, manipulated, misused.” I knew immediately what he was getting at. Since the night I received my LIFT assignment from Walter, I’d been writing down any words I remembered which were typical of my mother. I kept some of the notes in my purse, while others were on a notepad in the kitchen, and some I even stuck under my pillow. It would never have occurred to me that this innocent habit could be dangerous. Even in the office canteen or on the subway I jotted down words while I sat: “rolling pin, lipstick, sneak trick, turn-off, silver blossoms”—a thousand fragments, a kaleidoscope of memories, just as you jotted down phrases for a time in our apartment on Field : Yen tie. ss hen you were bored, without really intending anything lo) it And just as you threw those notes one after the other into your elegant wastebasket, so I destroyed all of mine after my teacher’s final visit, by burning them in the kitchen sink. The very next evening a young woman spoke to me in the lobby of the apartment building: Can you tell me where the lifts are?” Since she said “lifts- and not “lift,” I responded cautiously: “Which floor do you want?” She named one near the top of the building. I stepped into the elevator with her, but she didn’t get off at my floor. I felt my caution had been justified. When I returned to the living room after having showered, I was shocked to find her sitting on my couch. She came up to me and apologized: “I’m sorry. The lift brought me back to you.”

Martin Grzimek (Trutzhain, 8 april 1950)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 8e april ook mijn blog van 8 april 2018 deel 2.