De Duitse schrijver Kristof Magnusson werd geboren op 4 maart 1976 in Hamburg. Zie ook alle tags voor Kristof Magnusson op dit blog.

Uit: Ik was het niet (Vertaald door Hilde Keteleer)

“Ik vroeg de anderen wat ze ervan vonden dat Felix Magath nu trainer van Schalke werd. Iedereen kende alleen maar Bayern München. Natuurlijk wist ik wel dat het zinvol was om met de collega’s iets te gaan drinken.

Netwerken en zo. Het wás ook werk, maar niet zo productief dat je er een hele nacht aan hoefde te besteden. Waarom dronken ze niet gewoon twee pintjes, handelden intussen de hele riedel van Tottenham en Arsenal, Auditt, Range Rover en vrouwelijke collega’s af en gingen dan maffen?

Eindelijk ging de kroeg dicht. Ik liep naar het hotel en had al op de liftknop geduwd toen Vikram, de in Bombay geboren Arsenalfan, aan mijn mouw trok en me meezeulde naar de hotelbar, waar iedereen bij elkaar zat. ‘We drinken Jägermeister, man’, had hij gezegd, alsof ik dan als Duitser geen nee kon zeggen. En dus dronk ik. Veroorzaakte een pijnlijke stilte toen ik zei dat ik geen auto had. Om drie uur deed ik alsof ik naar de wc moest, liep naar mijn kamer, kotste, douchte, dronk twee liter water, nam twee magnesiumtabletten, drie paracetamols en een Pantozol, pakte mijn koffer, nam een taxi naar Heathrow en stapte om 5.03 uur in dit vliegtuig terug naar Chicago.

De stewardess nam mijn jasje aan en hing het op een knaapje, waaraan ze mijn instapkaart vastmaakte als een garderobenummer. Daarna kwam ze met een glas champagne.

Ik moest me beheersen om niemand te laten merken hoe blij ik was met mijn stoel in de businessclass. Per slot van rekening was deze vlucht geen cadeau van Rutherford & Gold maar een noodzakelijke uitgave.”

Kristof Magnusson (Hamburg, 4 maart 1976)

De Afghaanse schrijver Khaled Hosseini werd geboren op 4 maart 1965 in Kabul. Zie ook alle tags voor Khaled Hosseini op dit blog.

Uit: A Thousand Splendid Suns

“Later, when she was older, Mariam did understand. It was the way Nana uttered the wordnot so much saying it as spitting it at herthat made Mariam feel the full sting of it. She understood then what Nana meant, that a harami was an unwanted thing; that she, Mariam, was an illegitimate person who would never have legitimate claim to the things other people had, things such as love, family, home, acceptance.

Jalil never called Mariam this name. Jalil said she was his little flower. He was fond of sitting her on his lap and telling her stories, like the time he told her that Herat, the city where Mariam was born, in 1959, had once been the cradle of Persian culture, the home of writers, painters, and Sufis.

“You couldn’t stretch a leg here without poking a poet in the ass,” he laughed. Jalil told her the story of Queen Gauhar Shad, who had raised the famous minarets as her loving ode to Herat back in the fifteenth century. He described to her the green wheat fields of Herat, the orchards, the vines pregnant with plump grapes, the city’s crowded, vaulted bazaars.

“There is a pistachio tree,” Jalil said one day, “and beneath it, Mariam jo, is buried none other than the great poet Jami.” He leaned in and whispered, “Jami lived over five hundred years ago. He did. I took you there once, to the tree. You were little. You wouldn’t remember.”

It was true. Mariam didn’t remember. And though she would live the first fifteen years of her life within walking distance of Herat, Mariam would never see this storied tree. She would never see the famous minarets up close, and she would never pick fruit from Herat’s orchards or stroll in its fields of wheat. But whenever Jalil talked like this, Mariam would listen with enchantment. She would admire Jalil for his vast and worldly knowledge. She would quiver with pride to have a father who knew such things.

“What rich lies!” Nana said after Jalil left. “Rich man telling rich lies. He never took you to any tree. And don’t let him charm you. He betrayed us, your beloved father. He cast us out. He cast us out of his big fancy house like we were nothing to him. He did it happily.” Mariam would listen dutifully to this. She never dared say to Nana how much she disliked her talking this way about Jalil. The truth was that around Jalil, Mariam did not feel at all like a harami. For an hour or two every Thursday, when Jalil came to see her, all smiles and gifts and endearments, Mariam felt deserving of all the beauty and bounty that life had to give. And, for this, Mariam loved Jalil.”

Khaled Hosseini (Kabul, 4 maart 1965)

De Oostenrijkse dichter en schrijver Robert Kleindienst werd geboren op 4 maart 1975 in Salzburg. Zie ook alle tags voor Robert Kleindienst op dit blog.

Ich weiß, was es heißt, glücklich zu sein

wir zwei stehen hier also zu dritt und

halten die Hand fester. so viel Grün, wie uns

der Frühling schenkt, überrascht uns dann

doch, das hätten wir nur im Traum

gedacht. nicht im Traum aber spiegeln wir

uns im Weiher, sehen Entenküken

nach, die Spuren ziehen im Wasser.

am Horizont leuchten Berge weiß, wir

warten noch eine Weile, schwimmen

weiter, dem Ufer zu

Heute, vor langer Zeit

siehst du, die Schaukel steht still

in Sisak. siehst du, ein Kind

sitzt darauf, das keinen Schatten wirft,

bis es der Wind hebt ans andere Ufer.

wir warten nicht dort, es ist

schon zu spät, sagt man uns

in der Lobby. alle frühzeitig

abgereist. später werden wir

die Rechnung zahlen,

abfahren, ein einziges Mal

zurückblicken, zu sehen,

wer winkt

Einklang

Dieser ruhige Atem

neben meiner Nacht.

Diese kleine Hand

in meiner Welt, die sich

öffnet, die ich schließe

in mir.

Robert Kleindienst (Salzburg, 4 maart 1975)

De Russische dichteres en dissidente Irina Ratushinskaya werd geboren op 4 maart 1954 in Odessa. Zie ook alle tags voor Irina Ratushinskaya op dit blog.

And I undid the old shawl

And I undid the old shawl

And at once there came to rm:

The four winds from all the roads,

From the clouds; of the earth.

And the first wind sang Inc a song,

About a house behind a hlack mountain.

And the second wind told me

About an enchanted arquebus.

And the third wind began to dance,

And the fourth gave me a ring.

But the fifth wind came laughing

And I recognised his face.

And I asked: “Where have you come from?

And who has sent you to mc’?’

But he looked into my features

And said nothing.

And I touched his shoulder

And sent all the others away.

And this wind blew out the candle.

When night. fell.

Vertaald door David McDuff

Irina Ratushinskaya (Odessa, 4 maart 1954)

Cover

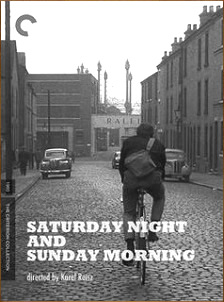

De Engelse schrijver Alan Sillitoe werd geboren op 4 maart 1928 in Nottingham. Zie ook alle tags voor Alan Sillitoe op dit blog.

Uit: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

““Loudmouth grunted and tried to ignore her eulogy, but at the end of a fiery and vivid description of a brothel in Alexandria he called over to Arthur: “I hear you drink a lot, matey?”

Arthur didn’t like being called “matey.” It put his back up straight away. “Middlin’,” he answered modestly. “Why?”

“What’s the most you’ve ever drunk, then?” Loudmouth wanted to know. “We used to have boozing matches on shore- leave,” he added with a wide, knowing smile to the aroused group of spectators. He reminded Arthur of a sergeant-major who once put him on a charge.

“I don’t know,” Arthur told him. “I can’t count, you see.”

“Well,” Loudmouth rejoined, “let’s see how much you can drink now. Loser pays the bill.”

Arthur did not hesitate. Free booze was free booze. Anyway, he begrudged big talkers their unearned glory, and hoped to show him up and take him down to his right size.

Loudmouth’s tactics were skilful and sound, he had to admit that. Having won the toss-up for choice, he led off on gins, and after the seventh gin he switched to beer, pints. Arthur enjoyed the gins, and relished the beer. It seemed an even contest for a long time, as if they would sit there swilling it back for ever, until Loudmouth suddenly went green halfway through the tenth pint and had to rush outside. He must have paid the bill downstairs, because he didn’t come back. Arthur, as if nothing had happened, went back to his beer.

He was laughing to himself as he rolled down the stairs, at the dull bumping going on behind his head and along his spine, as if it were happening miles away, like a vibration on another part of the earth’s surface, and he an earthquake-machine on which it was faintly recorded. This rolling motion was so restful and soporific, in fact, that when he stopped travelling-having arrived at the bottom of the stairs-he kept his eyes closed and went to sleep. It was a pleasant and faraway feeling, and he wanted to stay in exactly the same position for the rest of his life.”

Alan Sillitoe (4 maart 1928 – 25 april 2010)

Cover DVD

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 4e maart ook mijn twee vorige blogs van vandaag.