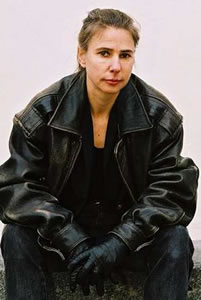

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Lionel Shriver werd als Margaret Ann Shriver geboren op 18 mei 1957 in Gastonia, North Carolina, in een diep religieuze familie (haar vader is een presbyteriaanse predikant). Op 15 jarige leeftijd veranderde ze haar naam van Margaret Ann in Lionel omdat haar de naam die ze had gekregen niet beviel en zij als “tomboy” van mening was dat een conventioneel mannelijke naam beter bij haar paste. Ze volgde een opleiding aan het Barnard College, Columbia University (BA, MFA). Ze heeft gewoond in Nairobi, Bangkok en Belfast en woont momenteel in Londen. In 2005 won zij de prestigieuze, exclusief voor vrouwelijke auteurs bestemde, Orange Prize voor haar controversiële roman We Need to Talk about Kevin. Daarin komt de verschrikkelijke vraag aan de orde: ligt het aan de opvoeding of aan de genen, als je eigen kind een moordenaar blijkt te zijn? In De wereld na zijn verjaardag vertelt Lionel Shriver opnieuw een aangrijpend verhaal, en werkt ze aan het einde twee opties voor haar personage uit: vreemdgaan of niet. Shriver’s nieuwste boek So Much for That verscheen in 2010.

Uit: So Much for That

“What do you pack for the rest of your life?

On research trips — he and Glynis had never called them “vacations” — Shep had always packed too much, covering for every contingency: rain gear, a sweater on the off chance that the weather in Puerto Escondido was unseasonably cold. In the face of infinite contingencies, his impulse was to take nothing.

There was no rational reason to be creeping these halls stealthily like a thief come to burgle his own home — padding heel to toe on the floorboards, flinching when they creaked. He had double-checked that Glynis was out through early evening (for an “appointment”; it bothered him that she did not say with whom or where). Calling on a weak pretense of asking about dinner plans when their son hadn’t eaten a proper meal with his parents for the last year, he had confirmed that Zach was safely installed at a friend’s overnight. Shep was alone in the house. He needn’t keep jumping when the heat came on. He needn’t reach tremulously into the top dresser drawer for his boxers as if any time now his wrist would be seized and he’d be read the Miranda.

Except that Shep was a burglar, after a fashion. Perhaps the sort that any American household most feared. He had arrived home from work a little earlier than usual in order to steal himself.

The swag bag of his large black Samsonite was unzipped on the bed, lying agape as it had for less drastic departures year after year. So far it contained: one comb.

He forced himself through the paces of collecting a travel shampoo, his shaving kit, even if he was doubtful that in The Afterlife he would continue to shave. But the electric toothbrush presented a quandary. The island had electricity, surely it did, but he’d neglected to discover whether their plugs were flat American two-prongs, bulky British three-prongs, or the slender European kind, wide-set and round. He wasn’t dead sure either whether the local current was 220 or 110. Sloppy; these were just the sorts of practical details that on earlier research forays they’d been rigorous about jotting down. But then, they’d lately grown less systematic, especially Glynis, who’d sometimes slipped on more recent journeys abroad and used the word vacation. A tell, and there had been several.“

Lionel Shriver (Gastonia, 18 mei 1957)