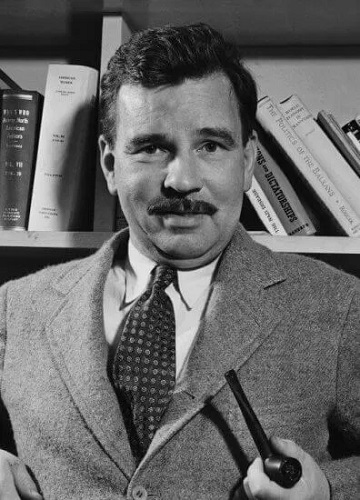

De Amerikaanse dichter en schrijver Malcolm Cowley werd geboren op 24 augustus 1898 in Belsano, Pennsylvania. Hij werd bekend als kroniekschrijver van de Amerikaanse moderniteit, in het bijzonder als auteur van “Exile’s Return” (1934), een ontnuchterende inventarisatie van de toestand van de ‘Lost Generation’ na hun terugkeer uit Europa. Cowley studeerde vanaf 1915 aan de Harvard University, waar hij onder meer lezingen volgde van de dichteres Amy Lowell. Toen de Verenigde Staten in 1917 aan de Eerste Wereldoorlog deelnamen, onderbrak hij zijn studie en sloot zich aan bij de American Field Service; hij werkte als ambulancechauffeur in Frankrijk. Gedurende deze tijd schreef hij oorlogsrapporten voor de Pittsburgh Gazette. In 1918 keerde hij terug en trouwde met de kunstenaar Peggy Baird. In 1920 voltooide hij zijn studie aan Harvard en verhuisde terug naar Frankrijk, waar hij zijn studie voortzette in Montpellier. In Europa sloot Cowley vriendschap met andere Amerikaanse expats, waaronder literaire grootheden uit die tijd als Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound en TS Eliot. In 1923 vestigde hij zich in Greenwich Village in New York en werd zo niet alleen een getuige van de Parijse Lost Generation, maar ook van de New York Jazz Age. In die tijd had hij vooral een hechte vriendschap met de dichter Hart Crane. Hij verdiende onder meer de kost door boekrecensies te schrijven voor het tijdschrift The Dial; Zijn eerste dichtbundel verscheen in 1929. Cowley’s huwelijk eindigde in een scheiding in 1931 en zijn ex-vrouw woonde bij Hart Crane totdat hij in april 1932 zelfmoord pleegde. Kort daarna trouwde Cowley voor de tweede keer met Muriel Maurer. Van 1929 tot 1944 was hij mederedacteur van The New Republic, een van de meest invloedrijke kranten van Amerikaans links. Zoals veel Amerikaanse intellectuelen uit die tijd raakte hij in de jaren dertig actief betrokken bij het politieke leven en werd hij steeds radicaler onder invloed van Theodore Dreiser; In 1935 was hij een van de oprichters van de linkse schrijversvereniging League of American Writers, waaruit hij in 1940 vertrok vanwege haar communistische oriëntatie. In 1937 verdedigde Cowley de Moskouse processen in de Nieuwe Republiek. In 1941, tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, werd Cowley de plaatsvervanger van Archibald MacLeish bij het Office of Facts and Figures, een agentschap van de regering-Roosevelt. Door tussenkomst van J. Edgar Hoover en rechtse journalisten werd hij echter al na een jaar ontslagen vanwege zijn politieke opvattingen. In 1949 werden ze opnieuw een probleem toen hij getuigde in het proces tegen Alger Hiss en de belangrijkste getuige van de aanklager, Whittaker Chambers, tegensprak. In de jaren vijftig werd Cowley medewerker van Viking Press, waarvoor hij edities van Amerikaanse klassiekers redigeerde. Cowley overleed op 27 maart 1989 in New Milford, Connecticut.

Boy in Sunlight

The boy having fished alone

down Empfield Run from where it started on stony ground,

in oak and chestnut timber,

then crossed the Nicktown Road into a stand

of bare-trunked beeches ghostly white in the noon twilight-

having reached a place of sunlight

that used to be hemlock woods on the slope of a broad valley,

the woods cut twenty years ago for tanbark

and then burned over, so the great charred trunks

lay crisscross, wreathed in briars, grey in the sunlight,

black in the shadow of saplings grown

scarcely to fishing-pole size: black birch and yellow birch,

black cherry and fire cherry-

having caught four little trout that float, white bellies up,

in a lard bucket half-full of lukewarm water-

having unwrapped a sweat-damp cloth from a slap of pone

to eat with dewberries picked from the heavy vine-

now sprawls above the brook on a high stone,

his bare scratched knees in the sun, his fishing pole beside him,

not sleeping but dozing awake like a snake on the stone.

Waterskaters dance on the pool beneath the stone.

A bullfrog goes silently back to his post among the weeds.

A dragonfly hovers and darts above the water.

The boy does not glance down at them

or up at the hawk now standing still in the pale-blue mountain sky,

and yet he feels them, insect, hawk, and sky,

much as he feels warm sandstone under his back,

or smells the punk-dry hemlock wood,

or hears the secret voice of water trickling under stone.

The land absorbs him into itself,

as he absorbs the land, the ravaged woods, the pale sky,

not to be seen, but as a way of seeing;

not to be judged, but as a way of judgment;

not even to remember, but stamped in the bone.

“Mine,” screams the hawk, “Mine,” hums the dragonfly,

and “Mine,” the boy whispers to the empty land

that folds him in, half-animal, half-grown,

still as the sunlight, still as the hawk in the sky,

still and relaxed and watchful as a trout under the stone.

POVERTY HOLLOW

Here in a mountain valley

we worked our fields till even the bottom land

was ribbed and gaunt as the horses, as the men.

This year our corn is blighted.

The valley is too narrow, and we have driven

our plows against the bony shanks of a hill.

Now rest, my brothers,

lie down together in a furrow. Rest,

and some day when the mineral earth has grown

cold as the moon’s craters, when the sun

fades in perpetual starlight, then our hills

will fold like wrinkles in a forehead, press

the valley out between than like slow fingers

against a bone-hard thumb, and so provide

for us magnificent burial, my kin.

Cold hills already lie

staring down at our cornfields hungrily.