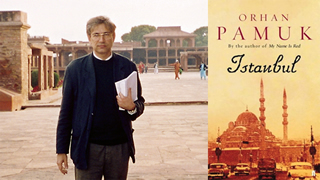

De Turkse schrijver Orhan Pamuk werd geboren op 7 juni 1952 in Istanbul. Zie ook alle tags voor Orhan Pamuk op dit blog.

Uit: Istanbul. Memories and the City (Vertaald door Maureen Freely)

“Here we come to the heart of the matter: I’ve never left Istanbul – never left the houses, streets and neighbourhoods of my childhood. Although I’ve lived in other districts from time to time, fifty years on I find myself back in the Pamuk Apartments, where my first photographs were taken and where my mother first held me in her arms to show me the world. I know this persistence owes something to my imaginary friend, and to the solace I took from the bond between us. But we live in an age defined by mass migration and creative immigrants, and so I am sometimes hard-pressed to explain why I’ve stayed not only in the same place, but the same building. My mother’s sorrowful voice comes back to me, ‘Why don’t you go outside for a while, why don’t you try a change of scene, do some travelling …?’

Conrad, Nabokov, Naipaul – these are writers known for having managed to migrate between languages, cultures, countries, continents, even civilisations. Their imaginations were fed by exile, a nourishment drawn not through roots but through rootlessness; mine, however, requires that I stay in the same city, on the same street, in the same house, gazing at the same view. Istanbul’s fate is my fate: I am attached to this city because it has made me who I am.

Flaubert, who visited Istanbul a hundred and two years before my birth, was struck by the variety of life in its teeming streets; in one of his letters he predicted that in a century’s time it would be the capital of the world. The reverse came true: after the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the world almost forgot that Istanbul existed. The city into which I was born was poorer, shabbier, and more isolated than it had ever been its two-thousand-year history. For me it has always been a city of ruins and of end-of-empire melancholy. I’ve spent my life either battling with this melancholy, or (like all Istanbullus) making it my own.

At least once in a lifetime, self-reflection leads us to examine the circumstances of our birth. Why were we born in this particular corner of the world, on this particular date? These families into which we were born, these countries and cities to which the lottery of life has assigned us – they expect love from us, and in the end, we do love them, from the bottom of our hearts – but did we perhaps deserve better?”

De Duitse schrijfster Monika Mann werd als vierde kind van Thomas Mann geboren op 7 juni 1910 in München. Zie ook alle tags voor Monika Mann op dit blog.

Uit: Das fahrende Haus

“Wer oder was war schuld? War dem Weißen Haus zu Ohren gekommen, daß ich gerne Tolstoi las und die Musik von Mussorgskij liebte? Waren es «linkselende», «peacemongerische», das heißt pazifistische Verwandte, war mein Plan, eine Reise nach Mexiko zu tun, war es die allgemeine Vorsicht der Regierung, die meine Fragen und Forschungen, unterstützt von einem in solchen Dingen gewiegten Rechtsanwalt, nichts fruchten ließ? (Es stand ja alles und manches andere mehr in jenem Aktenstoß.) Ich saß da also immer noch mit meinem (nunmehr ganz «anrüchigen») Ungarpaß.

Das ungarische Konsulat in New York war ausgezogen, umgezogen, stand überhaupt nicht im Telephonbuch. Man mußte wissen, daß es durch die Hintertüre einer britischen Institution im finstersten Downtown zu betreten war. War ich auch wohl ein wenig abgebrüht, so wurden doch Ohnmacht und Lachkitzel von damals jetzt zur regelrechten Furcht. Ich fühlte mich fehl am Platz, und ich fürchtete mich. Obgleich mein Mann Ungar gewesen war, habe ich nie ein besonderes Verhältnis zu seiner Heimat gehabt. Ihre Pferdesteppen, ihr buntes, kultiviertes Budapest, ihre Rhapsodien – ich kannte es aus der Ferne. Doch das, was mir immer an jenem Volk gefiel, war seine Weltaufgeschlossenheit, sein vielinteressiertes, kosmopolitisches Wesen.

Mein Mann war in den verschiedensten Sprachen und Kulturen zu Hause, und er war keine Ausnahme. Diese Herren hier – sie waren klein und geheimnisvoll – sprache überhaupt nur ungarisch. Sie flüsterten hinter staubigen Barrieren mit Seitenblicken nach meiner Person, sie verschwanden und kamen wieder – kopfschüttelnd, mit finster-listigem Grinsen, so schien mir, Namen aussprechend wie Rákosi und Búdapesti. Sie bedeuteten mir mit unheimlichem Händereiben in ihrer Sprache der Mai- käfer, wiederzukommen, ein andermal vielleicht . . .“

Hier op Capri met vriend Antonio Spadaro in de jaren 1970

De Amerikaanse dichteres en schrijfster Nikki Giovanni werd geboren op 7 juni 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee. Zie ook alle tags voor Nikki Giovanni op dit blog.

Rain

rain is

god’s sperm falling

in the receptive

woman how else

to spend

a rainy day

other than with you

seeking sun and stars

and heavenly bodies

how else to spend

a rainy day

other than with you

Cotton Candy On A Rainy Day

Don’t look now

I’m fading away

Into the gray of my mornings

Or the blues of every night

Is it that my nails

keep breaking

Or maybe the corn

on my secind little piggy

Things keep popping out

on my face or of my life

It seems no matter how

I try I become more difficult

to hold

I am not an easy woman

to want

They have asked

the psychiatrists . . . psychologists . . .

politicians and social workers

What this decade will be

known for

There is no doubt . . . it is

loneliness

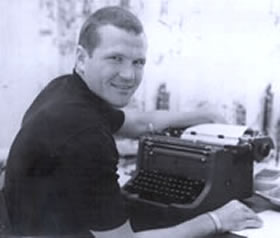

De Amerikaanse schrijver Harry Crews werd geboren op 7 juni 1935 in Bacon County, Georgia. Zie ook alle tags voor Harry Crews op dit blog.

Uit: Harry Crews On Writing

“I decided a long time ago—very long time ago—that getting up at four o’clock to start work works best for me. I like that. Some people don’t like to get up in the morning. I like to get up in the morning. And there’s no place to go at four o’clock in the morning, and nobody’s gonna call you, and you can’t call anybody. Back when I was a drunk, at least in this little town, there’s no place to go buy anything to drink. So it was just me and the writing board.

“So, I write until eight or eight-thirty, then I go over to the gym and work out on the weights for a couple hours, then I go to the karate dojo and, as a rule, spar with a guy who consistently whups my ass. It’s point karate—we’re not going full force, we don’t wear pads on out feet and hands, but—even then—when you’re just touching a guy, and you think a guy’s gonna move one way and you kick, and he doesn’t move that way, he moves the other way, he moves right into your kick, you can get hurt. Well, not hurt bad, as a rule. Maybe bloody a nose or something like that. But you can end up pretty sore.

“Then I come home, eat a light lunch, then just go straight back to the thing. I might work till three o’clock . . . there comes a time of diminishing returns. You’re just jerking yourself off thinking you’re doing some good work, then you go back to it the next day and you think, ‘Oh, my God,’ and you have to throw away two or three pages. But the way I do it—I don’t believe I’ve ever heard of anyone doin’ it quite this way.”

De Amerikaanse dichteres en schrijfster Louise Erdrich werd geboren op 7 juni 1954 in Little Falls, Minnesota. Zie ook alle tags voor Louise Erdrich op dit blog.

Uit: The Round House

“I was reading and drinking a glass of cool water in the kitchen when my father came out of his nap and entered, disoriented and yawning. For all its importance Cohen’s Handbook was not a heavy book and when he appeared I drew it quickly onto my lap, under the table. My father licked his dry lips and cast about, searching for the smell of food perhaps, the sound of pots or the clinking of glasses, or footsteps. What he said then surprised me, although on the face of it his words seem slight.

Where is your mother?

His voice was hoarse and dry. I slid the book on to another chair, rose, and handed him my glass of water. He gulped it down. He didn’t say those words again, but the two of us stared at each other in a way that struck me somehow as adult, as though he knew that by reading his law book I had inserted myself into his world. His look persisted until I dropped my eyes. I had actually just turned thirteen. Two weeks ago, I’d been twelve.

At work? I said, to break his gaze. I had assumed that he knew where she was, that he’d got the information when he phoned. I knew she was not really at work. She had answered a telephone call and then told me that she was going in to her office to pick up a folder or two. A tribal enrollment specialist, she was probably mulling over some petition she’d been handed. She was the head of a department of one. It was a Sunday—thus the hush. The Sunday afternoon suspension. Even if she’d gone to her sister Clemence’s house to visit afterward, Mom would have returned by now to start dinner. We both knew that. Women don’t realize how much store men set on the regularity of their habits. We absorb their comings and goings into our bodies, their rhythms into our bones. Our pulse is set to theirs, and as always on a weekend afternoon we were waiting for my mother to start us ticking away on the evening. And so, you see, her absence stopped time.“

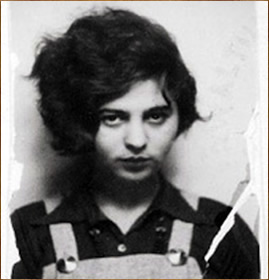

De Duitstalige dichteres Mascha Kaléko (eig. Golda Malka Aufen) werd geboren op 7 juni 1907 in Krenau of Schidlow in Galicië in het toenmalige Oostenrijk-Hongarije, nu Polen. Zie ook alle tags voor Mascha Kaléko op dit blog.

»Take it easy!«

Tehk it ih-sie, sagen sie dir.

Noch dazu auf englisch.

»Nimm’s auf die leichte Schulter!«

Doch, du hast zwei.

Nimm’s auf die leichte.

Ich folgte diesem populären

Humanitären Imperativ.

Und wurde schief.

Weil es die andre Schulter

Auch noch gibt.

Man muß sich also leider doch bequemen,

Es manchmal auf die schwere zu nehmen.

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 7e juni ook mijn blog van 7 juni 2011 deel 2.