De Amerikaanse schrijfster en essayiste Siri Hustvedt werd geboren op 19 februari 1955 in Northfield, Minnesota. Zie ook alle tags voor Siri Hustvedt op dit blog.

Uit: Living, Thinking, Looking

“DESIRE APPEARS AS A FEELING, a flicker or a bomb in the body, but it’s always a hunger for something, and it always propels us somewhere else, toward the thing that is missing. Even when this motion takes place on the inner terrain of fantasy, it has a quickening effect on the daydreamer. The object of desire—whether it’s a good meal, a beautiful dress or car, another person, or something abstract, such as fame, learning, or happiness—exists outside of us and at a distance. Whatever it is, we don’t have it now. Although they often overlap, desires and needs are semantically distinct. I need to eat, but I may not have much desire for what is placed in front of me. While a need is urgent for bodily comfort or even survival, a desire exists at another level of experience. It may be sensible or irrational, healthy or dangerous, fleeting or obsessive, weak or strong, but it isn’t essential to life and limb. The difference between need and desire may be behind the fact that I’ve never heard anyone talk of a rat’s “desire”—instincts, drives, behaviors, yes, but never desires. The word seems to imply an imaginative subject, someone who thinks and speaks. In Webster’s, the second definition for the noun desire is: “an expressed wish, a request.” One could argue about whether animals have “desires.” They certainly have preferences. Dogs bark to signal they wish to go outside, ravenously consume one food but leave another untouched, and make it known that the vet’s door is anathema. Monkeys express their wishes in forms sophisticated enough to rival those of their cousins, the Homo sapiens. Nevertheless, human desire is shaped and articulated in symbolic terms not available to animals.

When my sister Asti was three years old, her heart’s desire, repeatedly expressed, was a Mickey Mouse telephone, a Christmas wish that sent my parents on a multi-city search for a toy that had sold out everywhere.”

Siri Hustvedt (Northfield, 19 februari 1955)

De Engelse schrijfster Helen Fielding werd geboren in Morley, Yorkshire op 19 februari 1958. Zie ook alle tags voor Helen Fielding op dit blog.

Uit: Bridget Jones’s Diary

“Sorry. I got lost.”

“Lost? Durr! What are we going to do with you? Come on in!”

She led me through the frosted-glass doors into the lounge, shouting, “She got lost, everyone!”

“Bridget! Happy New Year!” said Geoffrey Alconbury, clad in a yellow diamond-patterned sweater. He did a jokey Bob Hope step then gave me the sort of hug which Boots would send straight to the police station.

“Hahumph,” he said, going red in the face and pulling his trousers up by the waistband. “Which junction did you come off at?”

“Junction nineteen, but there was a diversion …”

“Junction nineteen! Una, she came off at Junction nineteen! You’ve added an hour to your journey before you even started. Come on, let’s get you a drink. How’s your love life, anyway?”

Oh God. Why can’t married people understand that this is no longer a polite question to ask? We wouldn’t rush up to them and roar, “How’s your marriage going? Still having sex?” Everyone knows that dating in your thirties is not the happy-go-lucky free-for-all it was when you were twenty-two and that the honest answer is more likely to be, “Actually, last night my married lover appeared wearing suspenders and a darling little Angora crop-top, told me he was gay/a sex addict/a narcotic addict/a commitment phobic and beat me up with a dildo,” than, “Super, thanks.”

Not being a natural liar, I ended up mumbling shamefacedly to Geoffrey, “Fine,” at which point he boomed, “So you still haven’t got a feller!”

“Bridget! What are we going to do with you!” said Una. “You career girls! I don’t know! Can’t put it off forever, you know. Tick-tock-tick-tock.”

Helen Fielding (Morley, 19 februari 1958)

De Estlandse schrijver Jaan Kross werd geboren op 19 februari 1920 in Tallin. Zie ook alle tags voor Jaan Kross op dit blog.

Uit: Uncle (Vertaald door Eric Dickens)

“Why should the most valuable items be packed in the first place? To save them from air raids? All well and good. But not only for that reason. To also send them out of Estonia at the first opportunity! And why the hell should they have any interest in that? To rescue them from the impending battles in Tartu. Fine. But encouraging their theft?! No! The order the librarians had received was a monolithic order from a monolithic robot. Like the majority of orders at the time. Any attempt to sabotage it could in itself prove deadly. But a deadliness which may, in fact have spurred on rather than scared off. Lord knows. The order came from Berlin to Tallinn and Tallinn to Tartu like a vehicle speeding along on caterpillar tracks. Armoured, targeted and utterly merciless. Like most orders at that time. Resistance to the order shot up like so much grass (weeds, they would have said in the other camp). Victorious grass. Whose existence always presented the risk of a thickening of the blood, but which thrives and grow rank over everything. The result: the contents, numbers and addresses of the crates became all of a jumble.

Where what ended up, whether in Germany, Tallinn, Haapsalu or in the manor houses of the Province of Tartumaa, no one there ever found out for sure. Even now, in August ’45, no one had a complete overview. But one thing was clear: some of the crates, about two or three lorry loads, had ended up at Mardimäe Manor in the cellars of the present schoolhouse. And now that the order had been given to return evacuated books to Tartu, these too had to be returned. Lorries drove out, to that end, from locations in Tartu, including the University, to seven or eight places that week. So the chain split off in seven or eight different directions. It was therefore pretty unlikely that anything had been left to chance.”

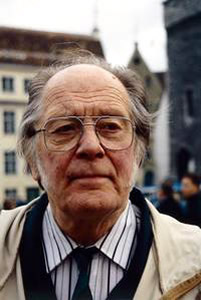

Jaan Kross (19 februari 1920 – 27 december 2007)

De Duitse schrijver Herbert Rosendorfer werd op 19 februari 1934 in Gries geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Herbert Rosendorfer op dit blog.

Uit: Deutsche Geschichte. Ein Versuch (Das Jahrhundert des Prinzen Eugen)

“Nach dem Ende des Dreißigjährigen Krieges war in Deutschland, und nicht nur in Deutschland,

nichts mehr so, wie es vorher gewesen war.

Die katholische Seite hatte den Krieg verloren, die protestantische Seite ihn nicht gewonnen. Das Deutsche Reich gab es noch, stark angeschlagen und verwundet, vor allem wirtschaftlich geschwächt. Der einzige Vorteil aus dem Frieden von Münster und Osnabrück für das Reich war, daß in gewisser Weise der verbleibende Rest, geographisch und institutionell gesehen, festgeschrieben und umrissen war. Die Regeln der Diplomatie, die in den folgenden Jahrhunderten das Scharnier aller Politik zumindest in Friedenszeiten bilden sollten, beruhten auf den mühsamen Errungenschaften des Westfälischen Friedensinstruments. Daß die Reichsgewalt, die Macht des Kaisers, in rasantem Sinken

begriffen war, konnte davon allerdings nicht aufgehalten werden. Vermutlich bewirkte nur das immer

zu beobachtende politische Beharrungsvermögen, daß das Reich die Katastrophe von 1618/48 um eineinhalb Jahrhunderte überdauerte.

Die kleinen oder sogar winzigen Territorialherrschaften wurstelten recht und schlecht vor sich hin. Sie waren, sofern nicht Reichsstädte oder geistliche Fürstentümer, Aufsplitterungen von ehemals größeren Gebieten.”

Herbert Rosendorfer (Gries, 19 februari 1934)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 19e februari ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag