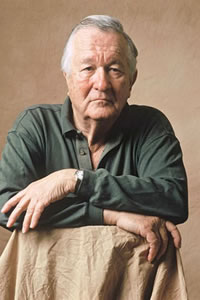

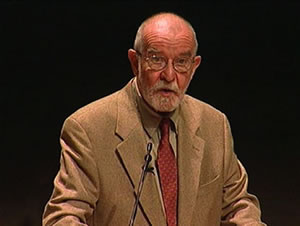

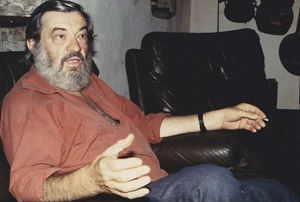

De Amerikaanse schrijver William Styron werd op 11 juni 1925 in Newport News in de staat Virginia geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor William Styron op dit blog.

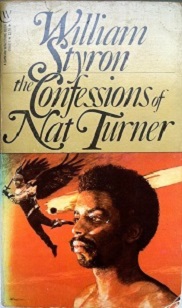

Uit: The Confessions of Nat Turner

“There

was nothing to say. “Well, you was a success, all right. Up to a point.

Mind you”—he jabbed a brown-stained finger at me—”up to a point.

Because, Reverend, basically speaking and in the profoundest sense of

the word you was a flat-assed failure—a total fiasco from beginning to

end insofar as any real accomplishment is concerned. Right? Because,

like you told me yesterday, all the big things that you expected to

happen out of this just didn’t happen. Right? Only the little things

happened, and them little things when they was all added up didn’t

amount to a warm bottle of piss. Right?” I felt myself shivering as I

gazed downward between my legs at the plank floor and at the links of

cold cast iron sagging like a huge rusting timber chain in the chill dim

light. Suddenly I felt the approach of my own death, and with a

prickling at my scalp, considered that death with mingled dread and

longing. My hands trembled, my bones ached, and I heard Gray’s voice as

if from a broad and wintry distance. “Item,” he persisted. “By the U. S.

census of last year there were eight thousand niggers in this county,

all chattel, not counting around fifteen hundred niggers that were free.

Of this grand total of ten thousand plus or minus whatever, you fully

expected a good percentage of the male population, at least, to rise up

and join you. Anyway, that’s what you have said, and that’s what the

nigger Hark and that other nigger, Nelson, before we hung him, said you

said. Let’s figure that, oh, maybe a little less than half of the nigger

population of the county lives along the route you traversed toward

Jerusalem. Lives within earshot of your clarion call, so to speak.

Counting on the bucks alone, that’s one thousand black people who might

be expected to follow your banner and live and die for Niggerdom, and

this is only if we figure that a pathetic fifty per cent of the eligible

males joined you. Not including pickaninnies and old uncles. One

thousand niggers you should have collected, according to your plans. One

thousand! And how in the forenoon of the second day when at some

pillaged ruin of a manor house far up-county I watched a young Negro I

had never seen before, outlandishly garbed in feathers and the uniform

of an army colonel, so drunk that he could barely stand, laughing

wildly, pissing into the hollow mouth of a dead, glassy-eyed

white-haired old grandmother still clutching a child as they lay

sprawled amid a bed of zinnias, and I said not a word to him, merely

turned my horse about and thought: It was because of you, old woman,

that we did not learn to fight nobly … “Last but not least,” Gray

said, “item. And a durned important item it is, too, Reverend, also

attested to by witnesses both black and white and by widespread evidence

so unimpeachable as to make this here matter almost a foregone

conclusion.”

Cover

De Nederlandse schrijfster Sophie van der Stap werd geboren in Amsterdam op 11 juni 1983. Zie ook alle tags voor Sophie van der Stap op dit blog.

Uit: Buiten spelen

“Het

is nu bijna drie jaar geleden dat ik Paloma heb ontmoet. Ik had toen

twee boeken op m’n naam staan; een biografisch boek en een tweede dat

ergens de weg tussen fictie en non-fictie was kwijtgeraakt. Wat kan ik

verder over toen zeggen? Ergens in huis lag een paspoort gevuld met

stempels en andere souvenirs aan mijn verre reizen. In míjn huis; niet

lang daarvoor had ik dankzij het succes van Meisje met negen pruiken een

appartement aan de Lijnbaansgracht kunnen kopen, maar ik stond heel

ergens anders: aan de voet van Montmartre en aan de voet van een nieuw

project, boek nummer drie. Mijn eerste echte boek, een roman, want écht

schrijven is toch veel meer dan een biografische overlevering. Al met al

was het een ander leven en misschien was ik toen ook wel een andere ik.

Alles zag er anders uit, of ik nou achterom keek of vooruit.

Ik koos

Parijs omdat ik me niet meer thuis voelde in mijn leventje in

Amsterdam. Het was te routineus, te ontdekt, te gemakkelijk misschien

ook.

Parijs was het tegenovergestelde; ik sprak de taal niet en op

mijn literaire agenten na – twee zes-talen-sprekende, drukke dames –

kende ik er niemand. In Amsterdam was ik inmiddels een big fish in a

small pond, in Parijs slechts een van de natgeregende jassen op straat

die stilletjes in de metro verdwijnen. Ik wilde uit die vissenkom

treden, uit mijn eigen ik. En dat lukte. Ik merkte dat de mensen me er

‘schoner’ bejegenden; zonder informatie is het moeilijk iemand te

plaatsen. Uit je buitenlandse accent kunnen ze niet opmaken of je van de

grachtengordel komt of uit Osdorp. Je bent onleesbaar, ongrijpbaar,

onaantastbaar. Je bent de buitenlander. Dat maakt wat alleenig, maar ook

universeler en uiteindelijk meer jezelf.”

De Zuid-Afrikaans schrijver en dichter Nicolaas Petrus van Wyk Louw werd geboren in Sutherland op 11 juni 1906. Zie ook alle tags voor N. P. van Wyk Louw op dit blog.

O suiwer hart

O suiwer hart wat honger was

in al jou lang deurwaakte nagte

na lewe en versadiging

van trane en lag en wilde klagte;

wat so ’n hoë gang wou gaan

en al Gods denke wou deurskou

soos water in jou hand gekelk

en in die witte son gehou;

wat alle vreugde wou besit

en àl wat die aarde aan skoonheid het

of sonde of smart, soos silwer vis

vang met die lyf se brose net;

– o bloed wat brand, o trotse hart,

nog roer om jou soos wind die smart,

maar in jou donker en hoë wil

word dit soos in ’n kamer stil

nou dat die bitter trots gaan skuil

in deernis soos ’n klippie sink

deur die grys-wit water van ’n kuil

en bewend daal deur kring nà kring

van aldeur sterker skemering

tot daardie stil en diep bestaan

waaroor die sware waters gaan.

God, dat hul smaad

God, dat hul smaad my nog kan raak,

my hart nog so verwondbaar is,

waar U groot wind moes óm my waai

vir hùl tot skriklike duisternis!

Ek sal nie twis en stry met hùl

wat self so magteloos is, gevang

in iedere dag se kleinlikheid

van smaad en wedersmaad en dwang –

met U, met U is my geding,

wat my geskei het van hul ras:

dat U die skulp van stilte breek

waarin ek so verborge was.

Was dit my woorde wat ek sê,

was my begeerte dan in my daad

dat U my nakend voor hul stel

en voor hul dwase Goed en Kwaad?

U moes die nag wees rondom my

omdat ek vir hul duister is;

U moes my skulp wees, of die see

waarin ek één vér spoeling is.

Adriaan Roland Holst, Jan Greshoff en NP van Wyk Louw

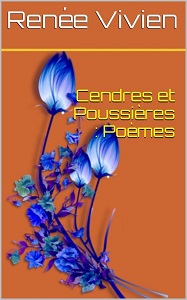

De Britse dichteres en schrijfster Renée Vivien (eig. Pauline Mary Tarn) werd geboren op 11 juni 1877 in Londen. Zie ook alle tags voor Renée Vivien op dit blog.

Victory

Give me kisses bitter as your tears tonight,

When birds pause in their flight to wait.

Our long loveless unions have the charms

Of plunder, and the feral lure of rape.

Your eyes reflect the splendor of the storm…

Breathe out your scorn until you swoon away,

My very dear!—Unclose your lips in wrath:

I’ll slowly drink their poison and their rage.

Roused as a pirate before his precious spoils,

Tonight when all your gaze’s glow has fled,

The conqueror’s soul, savage and radiant,

Sings in my triumph as I leave your bed!

Vertaald door Samantha Pious

You for whom I wrote

You for whom I wrote, oh lovely young women without names,

You whom, alone, I loved, will you reread my verse

On future mornings snowing coldly on the universe,

By future quiet evenings of roses and flames?

Will you sit dreaming, amid the charming disarray

Of dishevelled hair, open robes, of her you never discover

Wherever you look: “Whether on day of mourning or festival day,

This woman wore always her glance, her tips of a lover.”

Pale, giving forth a fragrance to haunt my flesh and mind,

In the magic evocation of the night when love should be rare and free

Will you say: “This woman had the ardor I can never find.

What a pity she is not living! She would have loved me!”

Cover

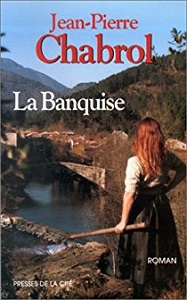

De Franse schrijver Jean-Pierre Chabrol werd geboren op 11 juni 1925 in Chamborigaud. Zie ook alle tags voor Jean-Pierre Chabrol op dit blog.

Uit: La banquise

« Là,

on fait place à Maurice Candelaire, dit « le Clouque » (celui qui

couve), cantonnier municipal, coiffeur le samedi soir et fossoyeur à

l’occasion. Le Clouque se hisse, aidé par des bras complaisants, sur la

charrette et se place derrière la rouquine. Il brandit glorieusement ses

ciseaux, pas ses outils de coiffeur, non ! des « forces », ciseaux

barbares qui ne sont utilisés que pour tondre les moutons. Il fait mine

de s’attaquer à l’ouvrage mais se recule sans arrêt pour exciter la

populace dont les vociférations s’élèvent dans l’aigu. Enfin le Clouque

attrape à pleines mains la longue crinière rousse et la tire brutalement

vers l’arrière, démasquant ainsi le visage de la prisonnière qu’il

force à se tourner dans tous les sens pour que les spectateurs, de plus

en plus montés, n’en perdent rien. La prisonnière est très pâle mais

impassible. Sa figure est large, de proportions harmonieuses, le nez

droit, les lèvres charnues. A peine quelques rides aux commissures et

des pattes-d’oie au coin des yeux qu’elle ne baisse pas. Des yeux usés,

d’un bleu pâli, ceux des bergers de transhumance, yeux étranges qui

voient au loin avec ce regard qui semble pourtant tourné vers

l’intérieur. Elle n’esquisse pas le moindre geste pour éviter les

projectiles, débris de boîtes de cigares, emballages froissés, tout ce

que les pillards du débit de tabac ont jeté par terre et que les plus

montés ramassent à présent. Enfin, les forces attaquent la chevelure en

prenant leur temps, avec, entre chaque mèche, de grands moulinets de

ciseaux qui cliquettent dans le vide. A mesure qu’apparaît la peau

blanche du crâne, les applaudissements crépitent et les gens commencent à

rire. Ils se regardent rire les uns les autres, comme si chacun avait

peur de rester le seul impassible, car alors toute tiédeur devient

suspecte. Ainsi les rires se multiplient, se nourrissant les uns des

autres à chaque boucle qui tombe, jusqu’à devenir un fracassant fou rire

qui secoue Bouscassel, d’autant plus violent qu’il est né d’une longue

peur. Le coiffeur jette les frisettes et les mèches aux mains qui se

tendent. Le soleil une seconde, au passage, les transforme en lambeaux

sanglants. Quand la tonte est terminée, le Clouque salue dans une

révérence outrée désignant d’une main son oeuvre. Alors, suivant une

voix surexcitée qui se met à brailler : « Allons enfants de la Patrie…

», la populace entonne La Marseillaise. Assis sur le marchepied de la

charrette, tourné vers la tondue, le Pétronille, un gros homme flasque,

la main droite mutilée, n’arrive pas à retenir de gros sanglots

d’enfant. Mais le Clouque trouve autre chose. Il enlève le panneau

infamant. Il pose ses mains sur les épaules de la tondue et d’un coup il

fait tomber le corsage. C’est d’abord deux robustes épaules, bien

rondes, d’une chair délicate. »

Cover

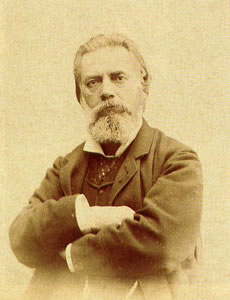

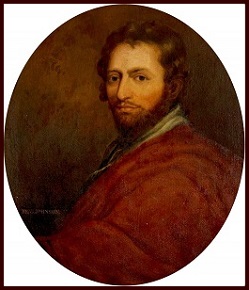

De Engelse dichter en schrijver Ben Jonson werd geboren rond 11 juni 1572 in Westminster, Londen. Zie ook alle tags voor Ben Jonson op dit blog.

Third Charm from Masque of Queens

The owl is abroad, the bat, and the toad,

And so is the cat-a-mountain,

The ant and the mole sit both in a hole,

And the frog peeps out o’ the fountain;

The dogs they do bay, and the timbrels play,

The spindle is now a turning;

The moon it is red, and the stars are fled,

But all the sky is a-burning:

The ditch is made, and our nails the spade,

With pictures full, of wax and of wool;

Their livers I stick, with needles quick;

There lacks but the blood, to make up the flood.

Quickly, Dame, then bring your part in,

Spur, spur upon little Martin,

Merrily, merrily, make him fail,

A worm in his mouth, and a thorn in his tail,

Fire above, and fire below,

With a whip in your hand, to make him go.

To Censorious Courtling

COURTLING, I rather thou should’st utterly

Dispraise my work, than praise it frostily:

When I am read, thou feign’st a weak applause,

As if thou wert my friend, but lack’dst a cause.

This but thy judgment fools: the other way

Would both thy folly and thy spite betray.

Anoniem portret in de Royal Shakespeare Theatrein Stratford-upon-Avon

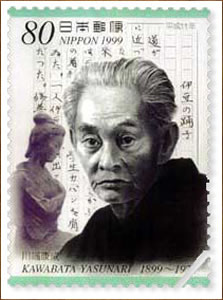

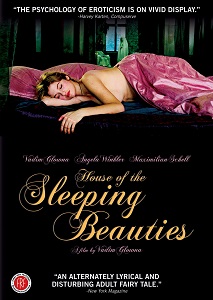

De Japanse schrijver Yasunari Kawabata werd geboren op 11 juni 1899 in Osaka. Zie ook alle tags voor Yasunari Kawabata op dit blog.

Uit: The House of the Sleeping Beauties (Vertaald door Edward Seidensticker)

“As Eguchi looked away his eye fell to his wrist watch.

“What time is it?”

“A quarter to eleven.”

“I should think so. Old gentlemen like to go to bed early and get up early. So whenever you’re ready.”

The woman got up and unlocked the door to the next room. She used her left hand. There was nothing remarkable about the act, but Eguchi held his breath as he watched her. She looked into the other room. She was no doubt used to looking through doorways, and there was nothing unusual about the back turned toward Eguchi.

Yet it seemed strange. There was a large, strange bird on the knot of her obi. He did not know what species it might be. Why should such realistic eyes and feet have been put on a stylized bird? It was not that the bird was disquieting in itself, only that the design was bad. But if disquiet was to be tied to the woman’s back, it was there in the bird. The ground was a pale yellow, almost white.

The next room seemed to be dimly lighted. The woman closed the door without locking it, and put the key on the table before Eguchi. There was nothing in her manner to suggest that she had inspected a secret room, nor was there in the tone of her voice.

Here is the key. I hope you sleep well. If you have trouble getting to sleep, you will find some sleeping medicine by the pillow.

“Have you anything to drink?”

“I don’t keep spirits.”

“I can’t even have a drink to put myself to sleep?”

“No.”

“She’s in the next room?”

“She’s asleep, waiting for you.”

“Oh!” Eguchi was a little surprised. When had the girl come into the next room? How long had she been asleep? Had the woman opened the door to make sure that she was asleep? Eguchi have heard by an old acquaintance who frequented the place that a girl would be waiting, asleep, and that she would not awake. But now that he was here he seemed unable to believe it.”

Poster voor de gelijknamige film van Vadim Glowna uit 2006

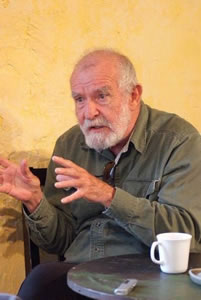

De Zuidafrikaanse schrijver Harold Athol Lannigan Fugard werd geboren op 11 juni 1932 in Middelburg, Kaapprovincie. Zie ook alle tags voor Athol Fugard op dit blog.

Uit: No–Good Friday

“GUY.

You mean the hotel? That’s the nearest I got to a job. They didn’t need

any musicians … ‘But we’ve got an opening for a kitchen boy’ …

‘Opening’, mind you! I should have told him, his opening was my back

door. Another bloke gives me a pat on the back after I’ve blown three

bars and says, ever so nicely: ‘You boys is just born musicians … born

musicians I tell you. You got it in your soul.’ So I says: ‘But a job,

Mister?’ And he says: ‘Nothing doing. Too many of you boys being born.’

You know something, Reb? I should have settled down to book learning.

That way you always eat. Like Willie. Now there’s a smart Johnny.

REBECCA. ‘Willie’s all right.

GUY. All right! He’s more than just right, he can’t go wrong.

REBECCA. He’s just like any other fellow.

GUY.

I didn’t mean it that way. I know Willie can go wrong, if he does some

stupid thing. What I mean is, it’s up to himself. But like me now … I

know I play well, everyone says so, even some of the top boys. But how

does that help me? I still get buggered around. And the way I see it

Willie won’t make no mistakes. What’s this latest thing he’s up to?

REBECCA. You mean the course?

GUY. Yes, that’s it.

REBECCA. First year B.A….Correspondent.

GUY. There, you see. Now who but Willie would think of that. [Pause.] Now … actually … where does that get him?

REBECCA. if he passes, to his second year.

GUY. Well, what do you know! [Pause.] And then?

REBECCA. The third year.

GUY. Doesn’t it end sometime?

REBECCA. If he passes that, he gets his degree. Bachelor of Arts.”

Scene uit een opvoering in Johannesburg, 2014

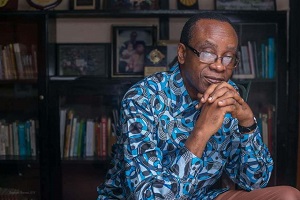

De Nigeriaanse dichter, schrijver, architect, en milieuactivist Nnimmo Bassey werd geboren in Akwa Ibom op 11 juni 1958. Zie ook alle tags voor Nnimmo Bassey op dit blog.

Uit: Power of poetry for global transformation

“Poetry

and song capture our understanding of life and provide us with

platforms to express ideas that may otherwise be inexpressible. Poetry

represents memory as well as vision. It is the chant as well as the

wail. It could come as joyous and exuberant calls, it could also come as

a dirge marking the crossing of the slim line between here and there,

between life on this plane and life across the river. The poet could be a

story teller, the griot, or the prophet. With eyes closed she sees

worlds that open-eyed folks are unable to comprehend.

In

sum, poetry is an expression of life. Poetry played a central role in

the precolonial African community. It still does. However, poetry in the

form of song is the dominant format in contemporary society. Dreams are

woven and conveyed through poetry. Defiance and censure equally find

potent expression in the medium. In other words, poetry can be

subversive and rallying cry for change.

As

a poet, I have noticed a progression in my relationship between my

thoughts, experiences and words. As a young poet, I was drawn to the

humour found in rhymes, limericks and the like. Poetry provided an

escape route in my struggles to understand the murky terrain of life. It

should be said that I grew up in at a time when my country and

continent faced serious political struggles. In the mid 1960s my country

was embroiled in the Nigeria-Biafra civil war. As a child I was witness

to brutality and suffered displacement and the indignities of being a

refugee in my own country. Thereafter, the struggle for independence in

other parts of Africa utterly radicalised by sensibilities. As all these

were going on, Nigeria suffered years of military dictatorship. Add to

these, the economic violence visited on Africa by international

financial institutions left deep questions. How do you say no in

thunder? – to use a phrase from one of the poems the poet Christopher

Okigbo (16 August 1932-1967). Okigbo died fighting for the Biafran

cause.”

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 11e juni ook mijn blog van 11 juni 2017 deel 2.