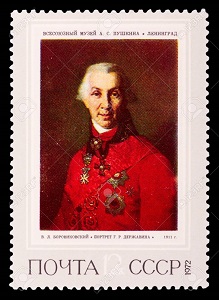

De Russische dichter Gavrila Romanovitsj Derzjavin werd geboren in Kazan op 14 juli 1743. Zie ook alle tags voor Gavrila Derzjavin op dit blog.

On The Death Of Prince Meshchersky (Fragment)

O, Voice of time! O, metal’s clang!

Your dreadful call distresses me,

Your groan doth beckon, beckon me

It beckons, brings me closer to my grave.

This world I’d just begun to see

When death began to gnash her teeth,

Like lightening her scythe aglint,

She cuts my days like summer hay.

No creature thinks to run away,

From under her rapacious claws:

Prisoners, kings alike are worm meat,

Cruel elements the tomb devour,

Time gapes to swallow glory whole.

As rushing waters pour into the sea,

So days and ages pour into eternity

And death carnivorous all eats.

We slide along the edge of an abyss

And we will someday topple in.

With life, we take at one time death,

To die’s the purpose of our birth.

Death strikes all down without a thought.

It shatters e’en the stars,

Extinguishes the suns,

It threatens every world.

Op een postzegel uit 1972

De Franse schrijfster van Belgische origine Béatrix Beck werd geboren in Villars-sur-Ollon op 14 juli 1914. Zie ook alle tags voor Béatrix Beck op dit blog.

Uit: La Petite Italie

“Au

dernier étage, dans un placard à balais coquettement aménagé, tapissé

d’échantillons de papier mural, vivotait la très vieille signora Cumini,

trois fois veuve et plus de dents. Elle dormait recroquevillée pour

pouvoir fermer sa porte. On la nourrissait gratis, les uns par

solidarité sociale, les autres pour l’amour de la bienheureuse Maria

Goretti, la grande Teresa ou, carrément, Dieu.

— Du pareil au même, chuintait Lucrezia Cumini.

Lait

de poule, purées de toutes choses, même gâtées, elle n’y voit que du

feu. Consommé où le chat mijote trois heures et demie, c’est pas la mort

d’un pape. Avec les herbes, un vrai lapin. La nonagénaire Lulu

larmoyait d’attendrissement en déglutissant.

Alida étreignit sa fille comme si elle venait d’échapper à un carnage,

coiffa de sa belle grande main abîmée la tête ronde de son fils, rasée à

cause des poux des riches :

— Mon cœur, qu’est ce que t’as fait à l’école aujourd’hui ?

— Rien.

— Oh, protesta Alia. Ils ont appris une chanson. Chante à maman.

— La pou-oule noire pond dans l’a-armoire.

— Et puis ?

— La poule blanche je sais pas.

La

toute petite Sandra donna de la voix. Mère et fille se jetèrent sur

elle, l’arrachèrent à son moïse, se l’arrachèrent. Alida dut lâcher

prise pour touiller la sublime soupe des premiers jours du mois, une

totalité, un absolu. Dans chaque assiette un filet d’or liquide. Mon

huile c’est mon sang, disait Alida en rebouchant serré le bidon. Fête

intérieure, recueillement. Seigneur, priait in petto Alida, mange avec

nous cette bonté.

Quand

le travail venait à manquer, on allait jusqu’à bouffer de l’herbe bien

bouillie, bien tordue, bien hachée. Les macaronis vivent de l’air du

temps, disaient les Français, les gaspilleurs, avec envie et mépris.

Après

le repas, succulent ou misérable, les trois enfants baisaient la main

de leur mère qui l’avait préparé, l’hommage de Nicola tenant plutôt du

suçon. Alida accueillait le cérémonial avec naturel et dignité. Essayait

de raconter à son mari : — La voisine… le boulanger… la pluie… —

Les ragots j’en ai rien à foutre. Parle-moi de la dictature du

prolétariat.”

De Amerikaanse schrijver, scenarioschrijver en regisseur Arthur Laurents is geboren in New York op 14 Juli 1918.Zie ook alle tags voor Arthur Laurents op dit blog.

Uit: West Side Story

“By

the time the mambo music starts the Jets and Sharks are each on their

own side of the hall. At the climax of the dance, Tony and Bernardo’s

sister, Maria, see one another :as a delicate cha-cha-cha, they slowly

walk forward to meet each other.

MEETING SCENE

TONY

You’re not thinking I’m someone else?

MARIA

I know you are not.

TONY

Or that we have met before?

MARIA

I know we have not.

TONY

I felt I knew something-never-before was going to happen, had to happen. But this is …

MARIA

interrupting

My hands are so cold.

He takes them in his.

Yours too.

He moves her hands to his face.

So warm.

She moves his hands to herface.

TONY

Yours, too…

MARIA

But of course. They are the same.

TONY

It’s so much to believe. You’re not joking me?

MARIA

I have not yet learned how to joke that way.

I think how I never will.

[JUMP]

Bernardo

is upon them in an icy rage. Chino, whom Bernardo has brought Maria

from Puerto Rico to marry, takes her home. Riff wants Bernardo for”War

Council”; they agree to meet in half an hour at Doc’s drugstore.”

Scene uit de film uit 1961 met Natalie Wood (Maria) and Richard Beymer (Tony)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Owen Wister werd geboren op 14 juli 1860 in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Zie ook alle tags voor Owen Wister op dit blog.

Uit: The Jimmyjohn Boss

“One

day at Nampa, which is in Idaho, a ruddy old massive jovial man stood

by the Silver City stage, patting his beard with his left hand, and with

his right the shoulder of a boy who stood beside him. He had come with

the boy on the branch train from Boise, because he was a careful German

and liked to say everything twice–twice at least when it was a matter

of business. This was a matter of very particular business, and the

German had repeated himself for nineteen miles. Presently the east-bound

on the main line would arrive from Portland; then the Silver City stage

would take the boy south on his new mission, and the man would journey

by the branch train back to Boise. From Boise no one could say where he

might not go, west or east. He was a great and pervasive cattle man in

Oregon, California, and other places. Vogel and Lex–even to-day you may

hear the two ranch partners spoken of. So the veteran Vogel was now

once more going over his notions and commands to his youthful deputy

during the last precious minutes until the east-bound should arrive.

“Und

if only you haf someding like dis,” said the old man, as he tapped his

beard and patted the boy, “it would be five hoondert more dollars salary

in your liddle pants.”

The

boy winked up at his employer. He had a gray, humorous eye; he was slim

and alert, like a sparrow-hawk–the sort of boy his father openly

rejoices in and his mother is secretly in prayer over. Only, this boy

had neither father nor mother. Since the age of twelve he had looked out

for himself, never quite without bread, sometimes attaining champagne,

getting along in his American way variously, on horse or afoot, across

regions of wide plains and mountains, through towns where not a soul

knew his name. He closed one of his gray eyes at his employer, and

beyond this made no remark.

“Vat you mean by dat vink, anyhow?” demanded the elder.

“Say,”

said the boy, confidentially–“honest now. How about you and me? Five

hundred dollars if I had your beard. You’ve got a record and I’ve got a

future. And my bloom’s on me rich, without a scratch. How many dollars

you gif me for dat bloom?” The sparrow-hawk sailed into a freakish

imitation of his master.

“You

are a liddle rascal!” cried the master, shaking with entertainment.

“Und if der peoples vas to hear you sass old Max Vogel in dis style they

would say, ‘Poor old Max, he lose his gr-rip.’ But I don’t lose it.”

His great hand closed suddenly on the boy’s shoulder, his voice cut

clean and heavy as an axe, and then no more joking about him. “Haf you

understand that?” he said.”

Cover

De Amerikaanse schrijver Willard Frances Motley werd geboren op 14 juli 1909 in Chicago. Zie ook alle tags voor Willard Motley op dit blog.

Uit: Alan M. Wald.American Night: The Literary Left in the Era of the Cold War (Hoofdstuk over Willard Motley)

“Like Oscar Wilde, Motley yearned for an escape from moralistic prohibi-tionism, but unlike Wilde he would not turn victimization into martyrdom. In personal notes he kept for a planned book-length novel about homosexual culture in the postwar era, he explained that he did not want to write the kind of book later known as the “Homosexual Problem Novel”; he hated the ones he read such as Gore Vidal’s The Pillar and the City (1946).107 He also refused to depict a homosexual as a redemptive figure, as in James Baldwin’s Another Country (1962). While Motley’s rejection of the available racial and gender definitions makes sense in a pre-Stonewall age, the absence of an alternative turned into a no-win predicament. Rather than producing fiction that replaced settled forms of identity with processes embedded in class, national, ethnic, and personal contexts, Motley could generate only a disconcerting sequence of enigmas and stereotypes. Hoist with his own petard of nondisclosure, Motley nonetheless partook, instinctively, of an “Adornian” dialectic through which his novels register a cognition of tension between concepts of race and gender and the non-conceptuality of the same. He merged with Petry and others in eroding prior categories, which in Petry’s case created a narrative that promoted a dissolu-tion of the 193os idea of the novel as reflective of the material configuration of experience. But anyone seeking in Motley a nimble and buoyant presenta-tion of such art will be disappointed. He aspired to panoramic volumes on a grand scale, and these are weighted with the deadly undertow of exhaustively researched sociological settings. Only a vigilant reader can discern how Mot-ley’s literary trajectory exhibits a process of paradoxical self-negation. Unlike Petry, there is no rematerializing logic to his texts through a vivid seizure of the imagination. In the eyes of his FBI watchers, Willard Motley was simply a “Negro writer with Leftist and homosexual tendencies who has lived in Mexico for a num-ber of years..”00 To understand more intricately what this redaction denoted, one needs to recover motives and meanings from Motley’s intimate life.”