De Britse schrijver Rhidian Brook werd geboren op 1 januari 1964 in Tenby. Zie ook alle tags voor Rhidian Brook op dit blog. Zie ook alle tags voor Rhidian Brook op dit blog.

Uit: Niemandsland (Vertaald door Maria Andreas)

“Die kleinen Wilden folgten ihrem Anführer über die Schutt-halde, die Augen angstvoll aufgerissen, das Weiß darin in den schmutzigen Gesichtern noch weißer. Sie schlichen durch Morä-nen aus Ziegelgestein, bis sie zu einer Lichtung kamen, auf der in voller Länge eine Kirchturmspitze lag. Osi stoppte die ande-ren mit einem Handzeichen und griff im Morgenmantel nach seiner Luger. Er witterte. »Da drinnen ist er. Ich kann ihn riechen. Riecht ihr ihn auch?. Die Wilden schnüffelten wie nervöse Kaninchen. Osi presste sich gegen die gefällte Turmspitze und schob sich Stück für Stück an das offene Ende heran, die Pistole wie eine Wünschel-rute vorgestreckt. Er blieb stehen und klopfte damit gegen den Stein, als wollte er sagen, da drinnen steck es, das Biest. Und dann ein schwarzer Blitz — etwas schoss ins Freie. Die Wilden duckten sich, doch Osi machte einen Ausfallschritt, stellte sich breit in Positur, kniff ein Auge zu, zielte und feuerte. »Stirb, Bestie! « Die drückende, feuchte Luft dämpfte den Schuss, und das metallische Zing eines Querschlägers meldete: Ziel verfehlt. »Hast du ihn getroffen?« Osi ließ die Pistole sinken und stieß sie in den Gürtel. »Wir kriegen ihn ein anderes Mal«, sagte er. »Suchen wir uns was zu essen.

»Wir haben ein Haus für Sie gefunden, Sir.« Captain Wilkins drückte seine Zigarette aus und legte den nikotingelben Zeigefinger auf den Hamburgplan, der hinter sei-nein Schreibtisch an der Wand hing. Er fuhr von dem Steckna-delkopf, der ihr provisorisches Hauptquartier markierte, nach Westen, weg von den ausgebombten Stadtteilen Hammcrbrook und St. Georg, über St. Pauli und Altona bis zu dem einstigen Fischerdorf Blankenese, wo die Elbe einen Bogen macht und in Richtung Nordsee fließt. Der aus einem deutschen Vorkriegs-reiseführer herausgerissene Stadtplan zeigte allerdings nicht, dass diese Ballungsgebiete nur noch eine Phantomstadt aus Schutt und Asche waren. »Ein Prachtpalast direkt am Fluss. Hier.« Wilkins umkreiste mit dem Finger die Biegung am Ende der Elbchaussee, die pa-rallel zum Elbstrom verlief. »Ich glaube, der wird nach Ihrem Geschmack sein, Sir.« Geschmack? Das Wort gehörte einer anderen Welt an, ei-ner Welt des Überflusses, ausgestattet mit allen zivilisatori-schen Annehmlichkeiten. Woran Lewis Geschmack fand, war in den letzten Monaten auf eine kurze Liste unmittelba-rer Grundbedürfnisse zusammengeschrumpft: 2500 Kalorien täglich, Tabak, Wärme. Ein »Prachtpalast am Fluss« kam ihm plötzlich vor wie die frivole Forderung eines ausschweifenden Königs. »Sir?« Lewis war wieder einmal »abwesend«, weggedriftet zu dem vielstimmigen Parlament in seinem Kopf, in dem er sich immer öfter in heiße Debatten mit Kollegen verstrickt sah. »Wohnt da nicht schon jemand?”

Rhidian Brook (Tenby, 1 januari 1964)

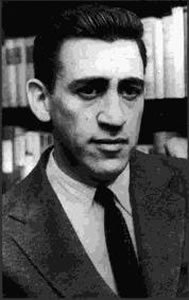

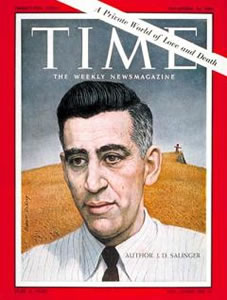

De Amerikaanse schrijver Jerome David Salinger werd in New York geboren op 1 januari 1919. Zie ook alle tags voor J. D. Salinger op dit blog.

Uit: The Catcher in the Rye

“Then the crook that had stolen them probably would’ve said, his voice very innocent and all, “What gloves?” Then what I probably would’ve done, I’d have gone in his closet and found the gloves somewhere. Hidden in his goddam galoshes or something, for instance. I’d have taken them out and showed them to the guy and said, “I suppose these are your goddam gloves?” Then the crook probably would’ve given me this very phony, innocent look, and said, “I never saw those gloves before in my life. If they’re yours, take ‘em. I don’t want the goddam things.” Then I probably would’ve just stood there for about five minutes. I’d have the damn gloves right in my hand and all, but I’d feel I ought to sock the guy in the jaw or something–break his goddam jaw. Only, I wouldn’t have the guts to do it. I’d just stand there, trying to look tough. What I might do, I might say something very cutting and snotty, to rile him up–instead of socking him in the jaw. Anyway if I did say something very cutting and snotty, he’d probably get up and come over to me and say, “Listen, Caulfield. Are you calling me a crook?” Then, instead of saying, “You’re goddam right I am, you dirty crooked bastard!” all I probably would’ve said would be, “All I know is my goddam gloves were in your goddam galoshes.” Right away then, the guy would know for sure that I wasn’t going to take a sock at him, and he probably would’ve said, “Listen. Let’s get this straight. Are you calling me a thief?” Then I probably would’ve said, “Nobody’s calling anybody a thief. All I know is my gloves were in your goddam galoshes.” It could go on like that for hours. Finally, though, I’d leave his room without even taking a sock at him. I’d probably go down to the can and sneak a cigarette and watch myself getting tough in the mirror. Anyway, that’s what I thought about the whole way back to the hotel. It’s no fun to he yellow. Maybe I’m not all yellow. I don’t know. I think maybe I’m just partly yellow and partly the type that doesn’t give much of a damn if they lose their gloves. One of my troubles is, I never care too much when I lose something–it used to drive my mother crazy when I was a kid. Some guys spend days looking for something they lost. I never seem to have anything that if I lost it I’d care too much. Maybe that’s why I’m partly yellow. It’s no excuse, though. It really isn’t. What you should be is not yellow at all. If you’re supposed to sock somebody in the jaw, and you sort of feel like doing it, you should do it. I’m just no good at it, though. I’d rather push a guy out the window or chop his head off with an ax than sock him in the jaw. I hate fist fights. I don’t mind getting hit so much–although I’m not crazy about it, naturally–but what scares me most in a fist fight is the guy’s face. I can’t stand looking at the other guy’s face, is my trouble. It wouldn’t be so bad if you could both be blindfolded or something.”

J.D. Salinger (1 januari 1919 – 27 januari 2010)

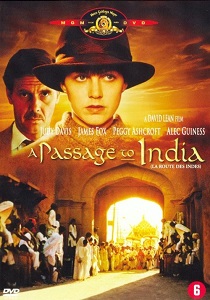

De Engelse romanschrijver en essayist Edward Morgan Forster werd geboren op 1 januari 1879 in Londen. Zie ook alle tags voor Edward Morgan Forster op dit blog.

Uit: A Passage to India

“Bribes?”

“Did you not know that when they were lent to Central India over a Canal Scheme, some

Rajah or other gave her a sewing machine in solid gold so that the water should run through his state?”

“And does it?

“No, that is where Mrs. Turton is so skilful. When we poor blacks take bribes, we perform what we are bribed to perform, and the law discovers us in consequence. The English take and do nothing. I admire them.”

“We all admire them. Aziz, please pass me the hookah.”

“Oh, not yet— hookah is so jolly now.”

“You are a very selfish boy.” He raised his voice suddenly, and shouted for dinner. Servants shouted back that it was ready. They meant that they wished it was ready, and were so understood, for nobody moved. Then Hamidullah continued, but with changed manner and evident emotion.

“But take my case—the case of young Hugh Bannister. Here is the son of my dear, my dead friends, the Reverend and Mrs. Bannister, whose goodness to me in England I shall never forget or describe. They were father and mother to me, I talked to them as I do now. In the vacations their Rectory became my home. They entrusted all their children to me— I often carried little Hugh about— I took him up to the Funeral of Queen Victoria, and held him in my arms above the crowd.”

“Queen Victoria was different,” murmured Mahmoud Ali.

“I learn now that this boy is in business as a leather merchant at Cawnpore. Imagine how I long to see him and to pay his fare that this house may be his home. But it is useless. The other Anglo-Indians will have got hold of him long ago. He will probably think that I want something, and I cannot face that from the son of my old friends. Oh, what in this country has gone wrong with everything, Vakil Sahib? I ask you.”

Aziz joined in. “Why talk about the English? Brrrr . . . ! Why be either friends with the fellows or not friends? Let us shut them out and be jolly. Queen Victoria and Mrs. Bannister were the only exceptions, and they’re dead.”

“No, no, I do not admit that, I have met others.”

“So have I,” said Mahmoud Ali, unexpectedly veering. “All ladies are far from alike.” Their mood was changed, and they recalled little kindnesses and courtesies. “She said ‘Thank you so much’ in the most natural way.” “She offered me a lozenge when the dust irritated my throat.”

Edward Morgan Forster (1 januari 1879 – 7 juni 1970)

DVD-cover voor de gelijknamige film uit 1984

De Colombiaanse schrijver Juan Gabriel Vásquez werd geboren in Bogotá op 1 januari 1973. Zie ook alle tags voor Juan Gabriel Vásquez op dit blog.

Uit: The Sound of Things Falling (Vertaald door Anne McLean)

“Nobody asked why he’d been killed, or who by, because such questions no longer had any meaning in my city, or they were asked in a mechanical fashion, as the only way to react to the latest shock. I didn’t think so at the time, but those crimes (magnicides, they called them in the press: I learned the meaning of that little word very early) had provided the backbone of my life or punctu-ated it like the unexpected visits of a distant relative. I was fourteen years old that afternoon in 1984 when Pablo Escobar killed or ordered the killing of his most illustri-ous pursuer, the Minister ofJustice Rodrigo Lara Bonilla (two hit men on a motorcycle, a curve on 127th Street). I was sixteen when Escobar killed or ordered the killing of Guillermo Cano, publisher of El Espectador (a few steps away from the newspaper’s offices, the assassin put eight bullets in his chest). I was nineteen and already an adult, although I hadn’t voted yet, on the day of the death of Luis Carlos Galan, a presidential candidate, whose assas-sination was different or is different in our imaginations because it was seen on TV: the crowd cheering Galan, then the machine-gunfire, then the body collapsing on the wooden platform, falling soundlessly or its sound hidden by the uproar or by the first screams. And shortly afterwards there was the Avianca plane, a Boeing 727-21 that Escobar had blown up in mid-air — somewhere in the air between Bogota and Cali — to kill a politician who wasn’t even on board. So all the billiard players lamented the crime with a resignation that was by then a sort of national idiosyn-crasy, the legacy of our times, and then we went back to our respective games. All, I mean, except for one whose attention remained riveted to the screen, where the images had moved on to the next news item and were now showing a scene of neglect: a bullring full of weeds as high as the flagpoles (or as high as the place where flags once flew), a roof over several vintage cars that were rusting away, a gigantic tyrannosaurus whose body was falling apart revealing a complicated metal structure, sad and naked like an old mannequin. It was the Hacienda Napoles, Pablo Escobar’s mythical territory, which had once been the headquarters of his empire, now left to its fate since the capo’s death in 1993.”

Juan Gabriel Vásquez (Bogotá, 1 januari 1973)

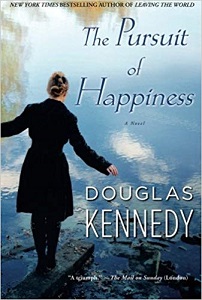

De Amerikaanse schrijver Douglas Kennedy werd geboren op 1 januari 1955 in New York. Zie ook alle tags voor Douglas Kennedy op dit blog.

Uit: The Pursuit of Happiness

“My seven-year-old son, Ethan, was tugging at my coat. His voice cut across that of the Episcopalian minister, who was standing at the back of the coffin, solemnly intoning a passage from Revelations:

God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; And there shall be no more death, neither sorrow Nor flying, neither shall there be any more pain; For the former things are passed away.

I swallowed hard. No sorrow. No crying. No pain. That was not the story of my mother’s life. “Mommy, Mommy …”

Ethan was still tugging on my sleeve, demanding attention. I put a finger to my lips and simultaneously stroked his mop of dirty blond hair. “Not now, darling,” I whispered. “I need to wee.” I fought a smile. “Daddy will take you,” I said, looking up and catching the eye of my ex-husband, Matt. He was standing on the opposite side of the coffin, keeping to the back of the small crowd. I had been just a tad surprised when he showed up at the funeral chapel this morning. Since he left Ethan and me five years ago, our dealings with each other had been, at best, businesslike—whatever words spoken between us having been limited to our son, and the usual dreary financial matters that force even acrimoniously divorced couples to answer each other’s phone calls. Even when he’s attempted to be conciliatory, I’ve cut him off at the pass. For some strange reason, I’ve never really forgiven him for walking right out of our front door and into the arms of Her—Ms. Talking Head News-Channel-4-New-York media babe. And Ethan was just twenty-five months old at the time. Still, one must take these little setbacks on the chin, right? Especially as Matt so conformed to male cliche. But there is one thing I can say in my ex-husband’s favor: he has turned out to be an attentive, loving father. And Ethan adores him—something that everyone at the graveside noticed, as he dashed in front of his grandmother’s coffin and straight into his father’s arms. Matt lifted him off the ground and I saw Ethan whisper his urination request. With a quick nod to me, Matt carried him off, draped across one shoulder, in search of the nearest toilet. The minister now switched to that old funeral favorite, the 23rd Psalm.”

Douglas Kennedy (New York, 1 januari 1955)

De Nederlandse schrijfster Rascha Peper (pseudoniem van Jenneke Strijland) werd geboren op 1 januari 1949 in Driebergen. Zie ook alle tags voor Rascha Peper op dit blog.

Uit: Zwartwaterkoorts

‘Met Gorredijk hier. Komt het gelegen dat ik u even over iets informeer?’ Zijn hart begon onaangenaam tegen zijn ribben te slaan,maar hij dwong zichzelf rustig te overleggenwat hij zou zeggen.

‘Het frappeert me dat u daarvoor de telefoon kiest,meneer Gorredijk, en niet het daarvoor geëigende middel, zoals we hadden afgesproken.’ Aan de andere kant werd gelachen.

‘Een brief bedoelt u?’

‘Precies.’

‘O, ik zal u heus wel een brief sturen, hoor.Maar een emailadres heeft u ook niet en ik wilde u snel iets laten weten, dus ik denk: ik pak maar even de telefoon.’

Stutijn zweeg. Hij staarde naar de schildpad, die net zijn waterbak verlaten had om een eindje over de kranten te kuieren, terwijl Scheffer, die ook de kamer binnengekomen was, op zijn schild sprong voor een ritje. De kraai was gek met de schildpad. Hij scherpte zijn snavel langs de randen van het schild en greep bij wijze van grap weleens een poot beet. De schildpad tolereerde hem.

‘Omdat ik u een aantrekkelijk voorstel wil doen,’ ging Gorredijk verder.

Juist vanwege de aantrekkelijke voorstellen had hij een half jaar geleden per aangetekende brief laten weten Gorredijk niet meer persoonlijk te woord te willen staan. Zolang hij op tijd de huur betaalde, kon niemand hem verplichten zich in levenden lijve of telefonisch aan contact te onderwerpen. Over de klachten van de buurt en de verbouwing van de zolderverdieping was hij sindsdien schriftelijk geïnformeerd. Hij las de brieven, maar reageerde er nooit op. Tot nu toe was die tactiek afdoende gebleken.

‘Daar ben ik niet in geïnteresseerd.’

‘Dat moet u niet meteen zeggen. Het kon wel eens in uw belang zijn.’

Hij keek toe hoe de kraai zich liet vervoeren, totdat de schildpad onder de laag afhangende citroengeraniums verdween en hij eraf geveegd werd. Hij had niet moeten zeggen dat hij niet geïnteresseerd was, maar gewoon: ik zie uw brief wel tegemoet.”

Rascha Peper (1 januari 1949- 16 maart 2013)

Driebergen, Sint Petrus’ Bandenkerk

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 1e januari ook mijn vorige twee blogs van vandaag.