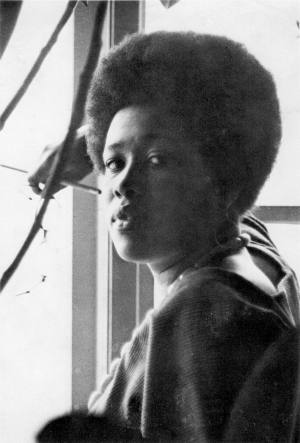

De Afro-Amerikaanse schrijfster Fran Ross werd geboren op 25 juni 1935 in Philadelphia als oudste dochter van Gerald Ross, een lasser, en Bernetta Bass Ross, een winkelbediende. Omdat haar schoolse, artistieke en atletische talenten werden onderkend kreeg ze een studiebeurs aan Temple University nadat ze op 15-jarige leeftijd haar diploma behaalde aan de Overbrook High School. Ross studeerde in 1956 af aan de Temple University met een bachelorsdiploma in communicatie, journalistiek en theater. Ze werkte korte tijd bij de Saturday Evening Post. Ross verhuisde in 1960 naar New York, waar ze solliciteerde om te werken voor McGraw-Hill en later Simon & Schuster als proeflezer, en waar ze onder andere aan het eerste boek van Ed Koch werkte. Ross begon haar roman “Oreo” in de hoop op een carrière als schrijfster en het boek werd in 1974 gepubliceerd op het hoogtepunt van de Black Power-beweging van de jaren zestig en zeventig. De titel van Ross komt van een wit en zwart koekje, gebruikt als etnisch scheldwoord in jargon, waarvan de Amerikaanse varianten een kenmerk van de roman zijn, en gebruikt de mythe van Theseus om het verhaal te vertellen van een zwart-joods meisje dat op zoek is naar, en uiteindelijk wraak neemt op haar vader. Ross schreef ook artikelen voor tijdschriften als Essence, Titters en Playboy, en werkte daarna mee aan The Richard Pryor Show. Ze was niet in staat een tweede roman af te ronden, omdat ze met dit werk moeilijk in haar levensonderhoud kon voorzien. Ze werkte in de media en uitgeverijen tot ze stierf aan kanker op 17 september 1985 in New York City. “Oreo” werd in 2000 herontdekt en opnieuw gepubliceerd door Northeastern University Press, met een nieuwe introductie door Harryette Mullen. “Oreo” werd in 2015 opnieuw gepubliceerd door New Directions en in Engeland in 2018 door Picador.

Uit: Oreo

“Food

Louise Clark’s southern accent was as thick as hominy grits. No one else in the Philadelphia branch of the family had such an accent. Her mother and father had dropped theirs as soon as they crossed the Pennsylvania state line. Her husband could have been an announcer for WCAU had they been hiring 10’s when he was coming up. While all about her sounded eastern-seaboard neutral, why did she persist in sounding like a mush-mouth? One reason: most of the time her mouth was full of mush or some other comestible rare or common to humankind.

Louise was once challenged to name a food she did not like. She paused to consider. That pause was now in its fifteenth year. During that time, she spoke of other things, lived her life, paid attention to what was going on, to all appearances; but all the while—simmering on a back burner, as it were—she was trying to bring to the boil of consciousness the category of food she had once tasted at Ida Ledbetter’s second child’s husband’s cousin’s wake after Ida Ledbetter’s second child’s husband’s cousin’s mother had collapsed after dishing out the potato salad. She would go to her reward without putting a name to that food, which was not food at all but a frying pan full of Oxydol. Why the Oxydol was in the frying pan in the first place is beyond the scope of this work, but when Louise had walked by the stove, she had hand-hunked a taste. Her judgment was that, whatever it was, someone had been a mite too heavy-handed with the salt. Thus, this was not truly her first antifood opinion but, rather, her first (and only) antiseasoning decision, an important subcategory. She always looked with perfect incomprehension on those finicky eaters who said that so-and-so’s spaghetti sauce was too spicy, her greens too bland, her sweet potatoes too stringy. For Louise, nothing to eat was ever too sour, salty, sweet, or bitter, too well done or too rare, too hot or too cold. Anything that could be subsumed under the general classification “Food” was exempt from criticism and was endued with all the attributes of pleasure. Consequently, anything Louise liked was compared, in one way or another, with food. A free translation of what she said on her wedding night after James went into his act would be: “The blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice.”

Aside on Louise’s speech

From time to time, her dialogue will be rendered in ordinary English, which Louise does not speak. To do full justice to her speech would require a ladder of footnotes and glosses, a tic of apostrophes (aphaeresis, hyphaeresis, apocope), and a Louise-ese/English dictionary of phonetic spellings. A com-promise has been struck. Since Louise can work miracles of compression through syncope, it is only fair that a few such condensations be shared with the reader. However, the substitu-tion of an apostrophe for every dropped g, missing r, and ab-sent t would be tantamount to tic douloureux of movable type.”