De Libanese (Franstalige) schrijver Amin Maalouf werd geboren in Beiroet, Libanon, op 25 februari 1949. Zie ook alle tags voor Amin Maalouf op dit blog.

Uit: De rots van Tanios (Vertaald door Eef Gratama)

“Het was heel lang geleden, ik was nog niet eens geboren, en mijn eigen vader ook nog niet. In die tijd voerde de pasja van Egypte oorlog tegen de Osmanen, onze voorouders hebben het niet makkelijk gehad. Vooral niet na de moord op de patriarch. Hij is precies daar, aan het begin van het dorp gedood, met het geweer van de consul van Engeland …’ Zo sprak mijn grootvader wanneer hij me geen antwoord wilde geven, hij uitte flarden van zinnen alsof hij een weg aanwees, dan weer een andere, vervolgens een derde, zonder ooit een ervan te volgen. Ik heb jaren moeten wachten voordat ik de ware toedracht ontdekte. Toch zat ik dicht bij de bron want ik kende de naam Lamia. Iedereen in de streek kende die naam, dankzij een gezegde dat ons bij toeval na een reis van twee eeuwen ter ore kwam: `Lamia, Lamia, hoe zou je je schoonheid kunnen verhullen?’ Nu nog, wanneer de jongelui die op het dorpsplein bij elkaar komen, een vrouw gehuld in een omslagdoek voorbij zien komen, is er altijd wel één die mompelt: `Lamia, Lamia …’ Wat vaak een welgemeend compliment is, maar soms ook het toppunt van wrede spot. De meesten van deze jongens weten niet veel van Lamia, noch van het drama dat dankzij dit gezegde niet in de vergetelheid is geraakt. Ze volstaan met te herhalen wat ze uit de mond van hun ouders en grootouders hebben gehoord, en soms maken ze daarbij, net als zij, een handgebaar in de richting van het hoger gelegen deel van het dorp, waar nu niemand meer woont en waar je de nog altijd de imposante ruïne van een kasteel kunt zien. Vanwege dat gebaar, dat ik zo vaak heb gezien, heb ik lange tijd gedacht dat Lamia een soort prinses was die haar schoonheid achter die hoge muren voor de blikken van de dorpelingen verhulde. Arme Lamia, als ik haar in de keukens in de weer had gezien, of blootsvoets lopend van het ene voorportaal naar het andere met een kruik in haar handen en een sjaal om haar hoofd, zou ik haar moeilijk voor de kasteelvrouwe hebben kunnen aanzien. Maar ze was evenmin een dienstmeisje. Nu weet ik iets meer over haar. In de eerste plaats dankzij de oude dorpelingen, zowel mannen als vrouwen die ik alsmaar met vragen heb bestookt. Dat was meer dan twintig jaar geleden, nu zijn ze allemaal dood, op één na. Zijn naam is Gebrayel, hij is een neef van mijn grootvader en is nu zesennegentig jaar oud. Dat ik hem ter sprake breng, komt niet alleen omdat hij het voorrecht heeft gehad de anderen te overleven, maar vooral omdat de getuigenis van deze voormalige onderwijzer met een hartstochtelijke belangstelling voor de plaatselijke geschiedenis het meest waardevol is geweest; in feite onvervangbaar. Ik kon uren naar hem blijven kijken, hij had grote neusgaten, dikke lippen en een klein, gerimpeld kaal hoofd —trekken die met het klimmen der jaren sterk de nadruk hebben gekregen. Ik heb hem de laatste tijd niet meer gezien, maar men verzekert mij dat hij nog altijd op dezelfde vertrouwelijke toon spreekt, met dezelfde waterval van woorden en een ijzeren geheugen. Tussen de woorden door die ik hierna op papier ga zetten, zal de lezer vaak de echo van zijn stem horen.”

Amin Maalouf (Beiroet, 25 februari 1949)

De Australische schrijver Gerald Murnane werd geboren op 25 februari 1939 in Coburg, Victoria. Zie ook alle tags voor Gerald Murnane op dit blog.

Uit: Border Districts

“Two months ago, when I first arrived in this township just short of the border, I resolved to guard my eyes, and I could not think of going on with this piece of writing unless I were to explain how I came by that odd expression.

I got some of my schooling from a certain order of religious brothers, a band of men who dressed each in a black soutane with a bib of white celluloid at his throat. I learned by chance last year, and fifty years since I last saw anyone wearing such a thing, that the white bib was called a rabat and was a symbol of chastity. Among the few books that I brought here from the capital city is a large dictionary, but the word rabat is not listed in it. The word may well be French, given that the order of brothers was founded in France. In this remote district, I am even less inclined than I was in the suburbs of the capital city to seek out some or another obscure fact; here, near the border, I am even more inclined than of old to accept as well-founded any supposition likely to complete a pattern in my mind and then to go on writing until I learn the meaning for me of such an image as that of the white patch which appeared just now against a black ground at the edge of my mind and will not be easily dislodged.

The school where the brothers taught was built in the grounds of what had been a two-storey mansion of yellow sandstone in a street lined with plane-trees in an inner eastern suburb of the capital city. The mansion itself had been converted into the brothers’ residence. On the ground floor of the former mansion, one of the rooms overlooking the return veranda was the chapel, which was used by the brothers for their daily mass and prayers but was available also to us, their students.

In the language of that place and time, a student who called at the chapel for a few minutes was said to be paying a visit. The object of his visitation was said to be Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament or, more commonly, the Blessed Sacrament. We boys were urged by teachers and priests to pay frequent visits to the Blessed Sacrament. It was implied that the personage denoted by that phrase would feel aggrieved or lonely if visitors were lacking. My class once heard from a religious brother one of a sort of story that was often told in order to promote our religious zeal. A non-Catholic of good will had asked a priest to explain the teachings of the Church in the matter of the Blessed Sacrament. The priest then explained how every disc of consecrated bread in every tabernacle in every Catholic church or chapel, even though it appeared to be mere bread, was in substance the body of Jesus Christ, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity. The inquirer of good will then declared that if only he were able to believe this, he would spend every free moment in some or another Catholic church or chapel, in the presence of the divine manifestation.”

Gerald Murnane (Coburg, 25 februari 1939)

De Nederlandse dichter, essayist, toneelschrijver, vertaler, kunstcriticus, journalist, redacteur en politicus Gabriël Wijnand Smit werd geboren in Utrecht op 25 februari 1910. Zie ook alle tags voor Gabriël Smit op dit blog.

Oud familieportret

Tussen de grote mensen – van de grond

gescheiden door een berg van brede plooien,

als op een onbereikbaar wereldrond –

zit zich het kind geduldig te verstrooien.

Het kijkt bevreemd de leegte in het rond:

het dikke kleed, de glinstering van het strooien

boeket, het grijze tuindoek, – al die mooie

dingen bekijkt het als een kleine hond.

Leeg is zijn hoofd achter de koele ogen,

zijn netvlies spiegelt alles onbewogen,

maar toch begint al in zijn rond gezicht

vermoeden van verwondering te trillen:

de mond bewoog, bevende om de stille

rimpeling van een wazig binnenlicht.

Tien sonnetten

V

En meer: Gij hebt ze om mij heen gezet,

uw hand even tevoren weggenomen

en warm van liefde, schuw in huiverend schromen,

vervullen zij hun opdracht: van uw wet

hier, voor mijn oog, de vaste stem te zijn,

mij dringend en vermanend niet te blijven

waar trots en zelfzucht mij willen inlijven

bij het verraad van hun devoten schijn.

Want alleen hier, in dit aandachtig spreken

met al wat Gij mij laat als troost en teeken,

ken ik de liefde, die de dag mij rooft.

Wat deed ik toch? Waar ben ik toch gebleven?

Bang keer ik terug naar wat mij heeft verdreven…

‘Caïn’, roept Gij, – en ik buig mijn hoofd.

Gabriël Smit (25 februari 1910 – 23 mei 1981)

De Britse dichter en schrijver Anthony Burgess werd geboren op 25 februari 1917 in Manchester, Engeland. Zie ook alle tags voor Anthony Burgess op dit blog.

Uit: Machten der duisternis (Vertaald door Paul Syrier)

“Ik bleef nog even liggen, naakt, vlekkerig, vaalbleek, uitgemergeld, een sigaret rokend die postcoïtaal had moeten zijn maar het niet was. Geoffrey trok puffend zijn sandalen aan, waarbij zijn buik zich in drie rollen vet plooide, en daarna zijn gebloemde overhemd. Ten slotte verborg hij zich achter zijn zonnebril, zo een van het onbeschofte soort waarvan de bolle oppervlakken de wereld een duo metalen spiegels voorhouden. Ik kon mijn eenentachtig jaar oude gezicht en hals er heel duidelijk in zien: de bekende afgeleefde grimmigheid van iemand die het leven intens heeft ervaren, de ontvleesde pezen als kabels, de anatomie van de kaken, de Fribourg & Treyersigaret in zijn Dunhillpijpje, die mijn herkomst verried uit een tijd waarin roken een handeling was die men met elegantie verrichtte. Ik bezag het dubbelbeeld zonder rancune, terwijl Geoffrey zei: ‘Ik vraag me af wat Zijne Aartsbisschap in de zin heeft. Misschien komt hij een excommunicatiebul afleveren. In kakelbonte cadeauverpakking, natuurlijk.’

‘Zestig jaar te laat,’ zei ik. Ik reikte Geoffrey de halfopgerookte sigaret aan om uit te drukken in een van de onyx asbakken en merkte op hoe ongaarne hij me zelfs die kleine dienst bewees. Ik stapte uit het bed, naakt, vlekkerig, vaal, uitgemergeld. Mijn zomerbroek zat, conform het fatsoensminimum, verre van strak. Het overhemd met begonia’s en orchideeën stond een man van mijn leeftijd belachelijk, maar ik had al lang geleden de angel uit Geoffreys rotopmerkingen getrokken met de woorden: ‘Lieve jongen, ik zal toch ééns moeten wennen aan het vooruitzicht van een laatste bloemenhulde.’ Deze zinsnede dateerde uit 1915. Ik had hem gehoord in Lamb House te Rye, maar hij was minder echt Henry James dan Henry James die de spot dreef met de echte Meredith. Hij had herinneringen opgehaald aan 1909 en het moment dat een of andere dame Meredith te veel bloemen had gestuurd. ‘Een laatste bloemenhulde, ha, ha, ha,’ had James gespot, schokschouderend van geveinsde vrolijkheid.

‘De gelukwensen van de tróúwe gelovigen, dan.’

Ik kon de overdreven stembuiging waarmee Geoffrey dit woord uitsprak geenszins waarderen. Het ademde seks en zijn eigen infame trouweloosheden; het was een woord dat ik ooit in tranen tegen hem had gebezigd; het was voor mij geladen met een ouderwetse morele ernst die voor Geoffreys generatie niet meer dan een nichtengrap was.”

Anthony Burgess (25 februari 1917 – 22 november 1993)

De Franse dichter Robert Rius werd geboren op 25 februari 1914 in Château-Roussillon. Zie ook alle tags voor Robert Rius op dit blog

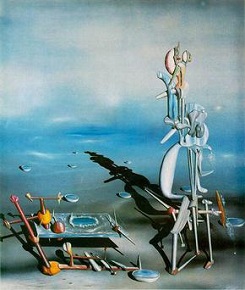

Uit: Votre vie vaut cinquante francs (mede ondertekend door André Breton, Henry Espinouze, Maurice Henry, Georges Hugnet, Jean, Benjamin Péret en Yves Tanguy)

« Deux cents francs pour quatre cadavres, on ne peut pas dire que ce soit cher. Soyons précis : Soixante-six francs soixante-six centimes, si l’on compte à sa juste valeur, c’est-à-dire rien, la carcasse de l’adjudant Untel, qui a trouvé une fin hono-rable dans l’exercice de ses sordides fonctions. Qu’on ne vienne pas nous dire que ce n’était pas sa faute. On ne devient pas adjudant comme on devient plombier; il faut la vocation. Après tout, Dreyfus n’avait qu’à ne pas être capitaine. Ça lui aurait évité des difficultés avec l’armée. Les paysans dont le sort nous touche aujourd’hui ont été assiégés dans leur ferme parce qu’ils devaient deux cents francs au fisc. On voit ici l’effet des direc-tions données par les responsables du Front Populaire aux percepteurs : accorder des facilités, ne pas instrumenter contre les gens trop visiblement désargentés. Il est très probable que les Cornuel auraient préféré payer deux cent francs que mourir grillés et mitraillés. 11 est entendu que le pauvre serrurier qu’ils ont descendu n’y était pour rien ; d’autant plus que si on l’avait laissé chez lui, il ne serait pas refroidi maintenant. Mais on a lancé des bombes lacrymogènes sur la vache des Cornuel. Erreur politique, d’ailleurs, il n’y avait rien d’autre à saisir dans leur lamentable ferme. On a mis le feu à la ferme (en sorte que l’enterrement des martyrs retombera finalement aux frais de la commune). Ne l’oubliez pas. Nous avons tous lu Sade avec un certain plaisir. N’oubliez pas la vieille paysanne qui fuyait la fournaise, les cheveux enflammés, canardée à loisir par des gendarmes épouvantés. »

Robert Rius (25 februari 1914 – 21 juli 1944)

Divisibilité indéfinie door Yves Tanguy, 1942

De Duitse schrijver Karl May werd geboren op 25 februari 1842 in Hohenstein-Ernstthal. Zie ook alle tags voor Karl May op dit blog.

Uit: Old Surehand

„Ich hatte dies natürlich in unsere Zeitrechnung zu übersetzen, und war zur bestimmten Zeit dort. Es war weder Winnetou noch eine Spur von ihm zu sehen, obgleich die Schattenlänge der Eiche genau fünfmal die meinige betrug. Ich wartete mehrere Stunden lang; er stellte sich nicht ein. Ich wußte, daß ihn nur ein Unfall hindern konnte, ein einmal gegebenes Wort zu halten, und wollte darum schon besorgt um ihn werden; da kam mir der Gedanke, daß er schon hier gewesen sein und einen triftigen Grund gehabt haben könne, nicht auf mich zu warten. In diesem Falle hatte er mir ganz gewiß ein Zeichen hinterlassen. Ich untersuchte also den Stamm der Eiche, und richtig! es steckte in demselben in Manneshöhe ein kleiner, verdorrter Fichtenzweig. Da eine Eiche keine Fichtenzweige hat, so mußte er mit Absicht angebracht worden sein, und zwar schon vor längerer Zeit, weil er vollständig vertrocknet war. Ich zog ihn heraus und mit ihm ein Papier, welches um sein zugespitztes, unteres Ende festgewickelt war. Als ich es aufgerollt hatte, las ich die Worte:

»Mein Bruder komme schnell zu Bloody-Fox, den die Comantschen überfallen wollen. Winnetou eilt, ihn noch rechtzeitig zu warnen.«

Diejenigen meiner Leser, welche Winnetou kennen, wissen, daß er sehr wohl lesen und auch schreiben konnte. Er führte fast stets Papier bei sich. Die Nachricht, welche ich hiermit von ihm erhielt, war keine gute; sie machte mich um ihn besorgt, obgleich ich wußte, daß er jeder, auch der größten Gefahr gewachsen sei. Auch um Bloody-Fox wurde mir bange, denn er war sehr wahrscheinlich verloren, wenn es Winnetou nicht gelang, ihn noch vor der Ankunft der Comantschen zu erreichen. Und was mich selbst betrifft, so war auch meine Lage nichts weniger als unbedenklich. Bloody-Fox hauste auf einer, ja wohl der einzigen Oase des öden Llano estakado, und der Weg dorthin führte durch das Gebiet der Comantschen, mit denen wir oft feindlich zusammengeraten waren.“

Karl May (25 februari 1842 – 30 maart 1912)

Pierre Brice als Winnetou en Stewart Granger als Old Surehand.in de gelijknamige film uit 1965

De Oekraïense dichteres, schrijfster en vertaalster Lesja Oekrajinka werd geboren op 25 februari 1871 in Novograd-Volynsky. Zie ook alle tags voor Lesja Oekrajinka op dit blog.

Uit: The Forest Song (Vertaald door Percival Cundy)

“The Lost Babes

Please, oh, please! be not so savage,

Or our home you’ll surely ravage.

One small cave – for there’s none other

Than the one found by our mother.

Humble is the place we own –

Father’s love we’ve never known…

(They seize him by the hand, beseeching him.)

We’ll dive down to depths profound

Where no light or warmth is found;

There Rusalka watch is keeping

Where a fisher drowned is sleeping.

“He Who Rends the Dikes”

Let her leave him lying there!

Straightway let her come up here!

(The Lost Babes dive down into the lake.)

Come up, love, I say!

Rusalka comes up out of the water, smiling alluringly, joyfully clapping her hands. She is wearing two chaplets: the larger one, green; the other, small, like a crown of pearls, from which there hangs a veil.

Rusalka

Ah! ‘tis you, my sweetheart gay.

“He Who Rends the Dikes”

(Angrily)

Why all this delay?

Rusalka

(She starts to swim as though to meet him, but veers aside, avoiding him.)

All the night, dear, I’ve been yearning,

Dreaming that you were returning!

All the many tears I wept

In a silver cup I’ve kept.

Without you, the tears, my lover,

Filled the cup till it brimmed over.

(She claps her hands, darts forward as though to meet his embrace, but again swerves aside and avoids him.)

Some gold to the bottom fling,

And baptize the wedding ring!

(She laughs in bell-like tones.) “

Lesja Oekrajinka (25 februari 1871 – 1 augustus 1913)

Scene uit een opvoering op Bainbridge Island, 2017

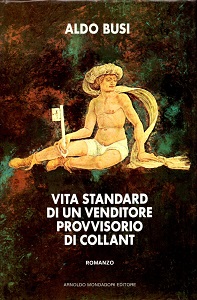

De Italiaanse schrijver en vertaler Aldo Busi werd geboren op 25 februari 1948 in Montichiari, Brescia. Zie ook alle tags voor Aldo Busi op dit blog.

Uit: Standard Life of a Temporary Pantyhose Salesman (Vertaald door Ercole Guidi)

“In the compartment Angelo had felt uneasy toward Jürgen Ölberg, his friend always so avid of new diseases; the venereal warts Jürgen had yet to collect, and he, who had been so close to getting them, had ran away, like any other mortal still contaminated by the categories of disease and cure.

But Angelo was fed up to the back teeth with clinical testing and rubber gloves. He might as well get used to dying of health, and not speak a word to Jürgen.

No sooner was he back home than he couldn’t wait a minute longer for the imminent inhalation.

The man by the white or red shorts was having a snack, light, together with that man and that woman likewise disdainful, without a reason, as they both were freckled and freckles are the demise of all regality on lakes that be not Scandinavian. Angelo felt as if three minutes and not three days had passed since the affront suffered. He must think of something else.

At Portese an old fisherman-innkeeper had complained of the increasingly meager catch because «the lake is inclined of the discharges. He saw a shim beneath Riva, as beneath the leg of a table, and the water overflowing in all the directions of the imaginary geographical vulva. But the first to be swept away and sucked into that «inclination» were always those three, placid and manducating, with their backs turned.

It was at that moment that he saw the yacht, which surely had been there for hours, pop out of nowhere and approach with precaution the emerging rocks.

Angelo was heedful of the signs of social opulence and genetic paucity which contemporarily intercross within the same family. One of the things which he found most horrifying (splendidly subversive: nothing like nature could intervene with a more candidly vindictive and revolutionary hand), was an economical empire founded upon a couple of dynamic and capable and with attitude to leading persons who had generated a seriously handicapped or mentally challenged as their sole heir.”

Aldo Busi (Montichiari, 25 februari 1948)

Cover Italiaanse uitgave

De Tsjechische dichter, journalist en vertaler Karel Toman werd geboren 25 februari 1877 in Kokovice. Zie ook alle tags voor Karel Toman op dit blog.

The Sundial

A house in ruins. On holed-out walls the moss

is creeping ravenous

and lichen hordes of infestation bask.

In the yard bindweed hustles

and nettles stand a-jungled. The poisoned well

is for the rats to drink.

A cankered apple tree, half lightning-felled,

strains, of past blooms to think.

On clear days come the whistles

as linnets rummage. On sun-glowing days

the gable-end sundial arc revives,

and on it carefree jolly flits and jives

time’s shadow

reciting skyward in stern righteous gloom:

Sine sole nihil sum.

For all is but a mask.

Vertaald door Václav ZJ Pinkava

Karel Toman (25 februari 1877 – 12 juni 1946)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 25e februari ook mijn 3 blogs van 25 februari 2018.