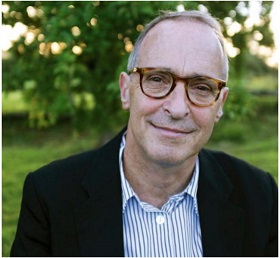

De Amerikaanse schrijver David Sedaris werd geboren in Binghamton, New York, op 26 december 1956. Zie ook alle tags voor David Sedaris op dit blog.

Uit: Calypso

“Though there’s an industry built on telling you otherwise, there are few real joys to middle age. The only perk I can see is that, with luck, you’ll acquire a guest room. Some people get one by default when their kids leave home, and others, like me, eventually trade up and land a bigger house. “Follow me,” I now say. The room I lead our visitors to has not been hastily rearranged to accommodate them. It does not double as an office or weaving nook but exists for only one purpose. I have furnished it with a bed rather than a fold-out sofa, and against one wall, just like in a hotel, I’ve placed a luggage rack. The best feature, though, is its private bathroom.

“If you prefer a shower to a tub, I can put you upstairs in the second guest room,” I say. “There’s a luggage rack up there as well.” I hear these words coming from my puppet-lined mouth and shiver with middle-aged satisfaction. Yes, my hair is gray and thinning. Yes, the washer on my penis has worn out, leaving me to dribble urine long after I’ve zipped my trousers back up. But I have two guest rooms.

The consequence is that if you live in Europe, they attract guests—lots of them. People spend a fortune on their plane tickets from the United States. By the time they arrive they’re broke and tired and would probably sleep in our car if we offered it. In Normandy, where we used to have a country place, any visitors were put up in the attic, which doubled as Hugh’s studio and smelled of oil paint and decaying mice. It had a rustic cathedral ceiling but no heat, meaning it was usually either too cold or too hot. That house had only one bathroom, wedged between the kitchen and our bedroom. Guests were denied the privacy a person sometimes needs on the toilet, so twice a day I’d take Hugh to the front door and shout behind us, as if this were normal behavior, “We’re going out for exactly twenty minutes. Does anyone need anything from the side of the road?”

That was another problem with Normandy: there was nothing for our company to do except sit around. Our village had no businesses in it and the walk to the nearest village that did was not terribly pleasant. This is not to say that our visitors didn’t enjoy themselves—just that it took a certain kind of person, outdoorsy and self-motivating. In West Sussex, where we currently live, having company is a bit easier. Within a ten-mile radius of our house, there’s a quaint little town with a castle in it and an equally charming one with thirty-seven antique stores. There are chalk-speckled hills one can hike up, and bike trails. It’s a fifteen-minute drive to the beach and an easy walk to the nearest pub.”

David Sedaris (Binghamton, 26 december 1956)

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Elizabeth Kostova werd geboren op 26 december 1964 in New London, Connecticut. Zie ook alle tags voor Elizabeth Kostova op dit blog.

Uit: The Shadow Land

“From her plane window, Alexandra had seen a city cradled in mountains and flanked by towering apartment buildings like tombstones. Stepping off the plane with her new camera in her hand, she’d breathed unfamiliar air—coal and diesel and then a gust that smelled of plowed earth. She had walked across the tarmac and onto the airport bus, observed shiny new customs booths and their taciturn officials, the exotic stamp in her passport. Her taxi had looped around the edges of Sofia and into the heart of the city—a longer route than necessary, she now suspected—brushing past outdoor café tables and lampposts that bore political placards or signs for sex shops. From the taxi window, she’d photographed ancient Fords and Opels, new Audis with tinted gangster windows, large slow buses, and trolleys like clanking Megalosauruses that threw sparks from their iron rails. To her amazement, she’d seen that the center of the city was paved with yellow cobblestones.

But the driver had somehow misunderstood her request and dropped her here, at Hotel Forest, not at the hostel she’d booked weeks earlier. Alexandra hadn’t understood the situation, either, until he was gone and she had mounted the steps of the hotel to get a closer look. Now she was alone, more thoroughly than she had ever been in her twenty-six years. In the middle of the city, in the middle of a history about which she had no real idea, among people who went purposefully up and down the steps of the hotel, she stood wondering whether to descend and try to get another taxi. She doubted she could afford the glass and cement monolith that loomed at her back, with its tinted windows, its crow-like clients in dark suits hustling in and out or smoking on the steps. One thing seemed certain: she was in the wrong place.

Alexandra might have stood this way long minutes more, but suddenly the doors slid open just behind her and she turned to see three people coming out of the hotel. One of them was a white-haired man in a wheelchair clutching several travel bags against his suit jacket.”

Elizabeth Kostova (New London, 26 december 1964)

De Britse schrijver, historicus, biograaf, criticus en vertaler Nigel Cliff werd geboren op 26 december 1969 in Manchester. Zie ook alle tags voor Nigel Cliff op dit blog.

Uit: Moscow Nights

“RILDIA BEE O’Bryan Cliburn’s proudest day was the day her son was born. She was thirty-seven and had been married to Harvey Lavan Clibum for eleven childless years. He was two years younger, a native of Mississippi whom she had met at an evening prayer meeting soon after breaking an engagement to a dentist. When she went to him one day in 1933 and said, “Sug, I think we’re going to have a little baby,” it seemed a miracle to them both. The following July 12 he came to her bedside at Tri-State Sanitarium in Shreveport, Louisiana— room 322, the number part of their personal liturgy—and smiled. “Babe,” he said in his laconic drawl, “we have a little boy, and this is our family.” The smiles dimmed when they differed over what to name the child—he wanted his son to have his name; she was not minded to raise a Junior—before harmony was restored with a compro-mise. The birth certificate duly recorded the debut of “Harvey Lavan (Van) Clibum,” but Rildia Bee made sure the child was never called anything but Van. Her second-proudest day was the day she met Sergei Rach-maninoff. It was two years earlier, and she was on a committee of musically minded ladies who had invited the Russian to Shreveport. The Clibums had moved to the city after her father, William Carey O’Bryan, who was mayor of McGregor, Texas, as well as a judge, state legislator, and newspaperman, convinced his son-in-law to make a career in oil. At the time, Harvey was a railroad station agent, but since his dream of being a doctor had been dashed in the Great War, and one thing was as good as an-other, he gamely signed up as a roving crude oil purchasing agent. Rildia Bee’s dream was to be a concert pianist, and she had indeed been on the brink of a career when her parents pulled her back from the unseemly business of performing in public. Since her mother, Sirrildia, had been a semiprofessional ac-tress—the only kind in those parts—that seemed a little unfair, but perhaps it was not, because Sirrildia refashioned herself into that primmest of creatures, a local historian, and the family was trying to put its stage days behind it. Rildia Bee dutifully de-moted herself to teaching piano, which was why she was on the Shreveport concert committee and came to tend personally to Rachmaninoff. Backstage at the big new Art Deco Municipal Auditorium, she had little to do except hand the famous Russian a glass of or-ange juice or water, and she never got to tell him that, pianisti-cally speaking, they were almost family. When she was a student at the Cincinnati conservatory, Rildia Bee had one day attended a recital by the famed pianist Arthur Friedheim, who despite his Germanic name was born to an aristocratic family in St. Peters-burg when it was the Imperial Russian capital. Mesmerized, she followed him to New York, where she became one of his best students at the Institute of Musical Art, a forerunner to the Mil-liard School. Friedheim had studied with the fiery Anton Rubinstein, the founder of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, before he balked at Rubinstein’s chaotic teaching style and defected to the superstar Hungarian Franz Liszt, becoming Liszt’s foremost pupil and, later, his secretary. Rachmaninoff counted Rubinstein as his greatest pianistic inspiration, and in his playing markedly resembled Friedheim, who had died less than a month earlier, leaving Rachmaninoff the greatest living exponent of the school of pianism that Rildia Bee adored.”

Nigel Cliff (Manchester, 26 december 1969)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Henry Miller werd geboren op 26 december 1891 In New York. Zie ook alle tags voor Henry Miller op dit blog.

Uit: The Colossus of Maroussi

“We awoke early and hired a car to take us to Epidaurus. The day began in sublime peace. It was my first real glimpse of the Peloponnesus. It was not a glimpse either, but a vista opening upon a hushed still world such as man will one day inherit when he ceases to indulge in murder and thievery. I wonder how it is that no painter has ever given us the magic of this idyllic landscape. Is it too undramatic, too idyllic? Is the light too ethereal to be captured by the brush? This I can say, and perhaps it will discourage the over-enthusiastic artist: there is no trace of ugliness here, either in line, color, form, feature or sentiment. It is sheer perfection, as in Mozart’s music. Indeed, I venture to say that there is more of Mozart here than anywhere else in the world. The road to Epidaurus is like the road to creation. One stops searching. One grows silent, stilled by the hush of mysterious beginnings. If one could speak one would become melodious. There is nothing to be seized or treasured or cornered off here: there is only a breaking down of the walls which lock the spirit in. The landscape does not recede, it installs itself in the open places of the heart; it crowds in, accumulates, dispossesses. You are no longer riding through something—call it Nature, if you will —but participating in a rout, a rout of the forces of greed, malevolence, envy, selfishness, spite, intolerance, pride, arrogance, cunning, duplicity and so on. It is the morning of the first day of the great peace, the peace of the heart, which comes with surrender. I never knew the meaning of peace until I arrived at Epidaurus. Like everybody I had used the word all my life, without once realizing that I was using a counterfeit. Peace is not the opposite of war any more than death is the opposite of life. The poverty of language, which is to say the poverty of man’s imagination or the poverty of his inner life, has created an ambivalence which is absolutely false. I am talking of course of the peace which passeth all understanding. There is no other kind. The peace which most of us know is merely a cessation of hostilities, a truce, an interregnum, a lull, a respite, which is negative. The peace of the heart is positive and invincible, demanding no conditions, requiring no protection. It just is. If it is a victory it is a peculiar one because it is based entirely on surrender, a voluntary surrender, to be sure. There is no mystery in my mind as to the nature of the cures which were wrought at this great therapeutic center of the ancient world. Here the healer himself was healed, first and most important step in the development of the art, which is not medical but religious. Second, the patient was healed before ever he received the cure. The great physicians have always spoken of Nature as being the great healer.”

Henry Miller (26 december 1891 – 7 juni 1980)

Hier aankomend op Schiphol in 1959

De Duitse dichter Rainer Malkowski werd geboren op 26 december 1939 in Berlijn-Tempelhof. Zie ook alle tags voor Rainer Malkowski op dit blog.

Die Gerechtigkeit des Meeres

Kein Element,

in dem man billig

Spuren hinterläßt.

Das bewegte Wasser

hinter dem Heck

bewahrt der glücklichen Fahrt

kein Gedächtnis.

Nur die Gescheiterten

dürfen

noch ein paar Jahrhunderte

ihre Geschichten erzählen −

jedem, der sie hören will

und zu den zerbrochenen

Schiffen

hinabsteigt auf den mythischen

Grund.

Im Jahr X

Hinter ihnen die Nacht.

Vor ihnen ein Raum,

bis an die Decke gefüllt

mit erfundenem Licht.

Sie halten die Scheibe besetzt

und rühren sich nicht.

Winzige, flugfähige Stifte.

Nur ihre Fühler sind in Bewegung −

Sicheln

von symmetrischer Anmut −,

während jetzt im Radio

das Zeitzeichen ertönt: im Jahr X

nach der Ursuppe.

Ein sprechendes Wesen

wird vorgestellt

und hält einen Vortrag

über den Tod

ferner Sterne.

Rainer Malkowski (26 december 1939 – 1 september 2003)

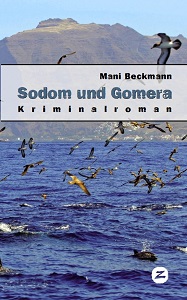

De Duitse schrijver Mani Beckmann (pseudoniem Tom Finnek) werd geboren op 26 december 1965 in Alstätte/Westfalen. Zie ook alle tags voor Mani Beckmann op dit blog.

Uit: Sodom und Gomera

„Das Taxi hielt, Micki zahlte die 2.500 Peseten (er tat dies wortlos), und Sandy forderte von mir die Hälfte des Fahrpreises, indem sie sagte: »Fifty-fi fty, ganz reell!« Als sie m einen fragenden Blick sah, fügte sie achselzuckend hinzu: »Wir sind zwei Parteien: du und wir. Also jeder die Hälfte.« Kopfschüttelnd gab ich ihr 1.500 Peseten und war etwas erstaunt, als sie sie einsteckte, ohne Anstalten zu machen, mir den Rest herauszugeben. Wieder sah sie mein Stirnrunzeln und meinte in vorwurfsvollem Ton: »Bisch du etwa ’n Pfennigfuchser?« Ich lächelte nachsichtig und verneinte ihre Frage. »Siehscht?«, fragte Sandy. »Da vorn isch auch schon die Fähre, wo nach San Sebaschtián fährt.« »San Sebastián?« »Des isch die Hauptstadt von Gomera. Und der Hafen. Das Valle isch auf der anderen Seite der Insel.« Auch während der gut einstündigen und erstaunlich schaukelfreien Schiff fahrt mit der »Ferry Gomera« gelang es mir nicht, den Redeschwall meiner neuen Bekannten zu bremsen oder auf eine andere Person (zum Beispiel ihren apathisch schweigenden Freund) zu lenken. Sie erzählte vermeintlich ulkige Anekdoten von vergangenen Urlaubstrips (sie reiste zum vierten Mal »ins Valle«), schwärmte von dem mojo bei Maria (eine Art Soße oder Dip, angeblich eine kulinarische Spezialität auf der Insel), dozierte über die »Guanchen«, die geheimnisumwitterten Ureinwohner der Kanaren, und berichtete von der so genannten Schweinebucht und den Freaks und Späthippies, die dort direkt am Wasser in Höhlen lebten, sich von Joints und freier Liebe ernährten und denen sich Sandy und Micki (selbstredend) auf der Stelle anschließen wollten.“

Mani Beckmann (Alstätte, 26 december 1965)

Cover

De Cubaanse schrijver, essayist en musicoloog Alejo Carpentier werd geboren in Havana op 26 december 1904. Zie ook alle tags voor Alejo Carpentier op dit blog.

Uit: The Kingdom of This World (Vertaald door Harriet de Onís)

“All of this became particularly evident to me during my stay in Haiti, where I found myself in daily contact with something we could call the marvelous real . I was treading earth where thousands of men, eager for liberty, believed in Mackandal’s lycanthropic powers, to the point that their collective faith produced a miracle on the day of his execution. I already knew the prodigious story of Bouckman, (21) the Jamaican initiate. I had been in the citadel of La Ferriere, a structure without architectonic precedents, portended only in Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons. I had breathed the atmosphere created by Henri Christophe, a monarch of incredible undertakings, much more surprising than all the cruel kings invented by the surrealists, who were very fond of imaginary tyrannies, never having suffered through one.

I found the marvelous real with every step. But I also realized that the presence and vitality of the marvelous real was not a privilege unique to Haiti but the patrimony of all the Americas, where we have not yet established an inventory of our cosmogonies. The marvelous real is found at each step in the lives of the men who inscribed dates on the history of the Continent and who left behind names still borne by the living: from the seekers after the Fountain of Youth or the Golden City of Manoa to certain early rebels or modern heroes of our wars of independence, those of such mythological stature as Colonel Juana Azurduy. It has always seemed significant to me that as recently as 1780 some perfectly sane Spaniards from Angostura set out in search of El Dorado, and that, during the French Revolution– long live Reason and the Supreme Being!–Francisco Menendez, from Compostela, traversed Patagonia hunting for the Enchanted City of the Caesars. Looking at the matter in another way, we see that while in western Europe folk-dancing has lost all its magical evocative power, it is rare that a collective dance in the Americas does not embody a profound ritual meaning that creates around it an entire initiatory process: such are the santeria dances in Cuba or the prodigious African version of the Corpus feast, which may still be seen in the town of San Francisco de Yare in Venezuela.”

Alejo Carpentier (26 december 1904 – 24 april 1980)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 26e december ook mijn vorige twee blogs van vandaag.