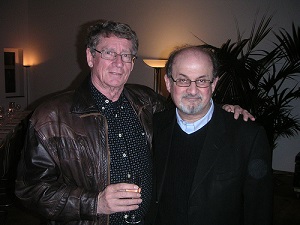

De Zuid-Afrikaanse schrijver André Brink werd geboren op 29 mei 1935 in Vrede. Zie ook alle tags voor André Brink op dit blog.

Uit: The blue door

“The urge to touch her becomes hard to resist. But I am restrained by the uncertainty about what might happen if I do. And there is the pure visual joy of looking at her. For the time being I do not want to do anything except to look, and look, and look. (How I wish I could paint her as she lies there now, at this moment, so close, so real.)

After a while, from the way in which she remains almost motionless, never bothering to turn a page, I realise that she is not reading either. Waiting for me to make the first move?

I move my hand closer to her, still without touching.

I seem to detect the merest hint of a stiffening in her body. But it may well be my imagination. And it is of decisive importance that I be sure before I risk an approach. Because if not…

‘What are you reading?’ I ask. But my voice is so strained that I have to clear my throat and repeat the question.

‘Haruki Murakami,’ she says, turning slightly over on her back and raising the book to let me see it. ‘Sputnik Sweetheart.’

‘What’s it like?’

‘A strange book,’ she says without looking at me. ‘I don’t think it’s entirely convincing, but it’s very disturbing.’ Now she settles squarely on her back and turns her head to look at me. ‘In the key episode of the story the young Japanese woman – what’s her name?’ She flips through a few pages. ‘Yes: Miu. She gets stuck at the top of a Ferris wheel at a fair in the middle of the night. And when she looks around, she discovers that she can see into her own apartment in the distance. And there’s a man in there, a man who has recently tried to get her into bed. While Miu is looking at him, she sees a woman with him. And the woman is she herself, Miu. It is a moment so shocking that her black hair turns white on the spot.’ Her black eyes look directly into mine. ‘Can you imagine a thing like that happening? Shifting between dimensions, changing places with herself…?’

‘I think that happens every day,’ I say with a straight face.

‘What do you mean?’

‘When one makes love. Don’t you think that’s a way of changing places with yourself? The world becomes a different place. You are no longer the person you were before.’

André Brink (29 mei 1935 – 6 februari 2015)

De Catalaanse dichter, schrijver en vertaler Eduard Escoffet werd geboren op 29 mei 1979 in Barcelona. Zie ook alle tags voor Eduard Escoffet op dit blog.

holz im herz (fragment)

holz im herz

holz im hirn

holz in den gedärmen

ein mann geht zur toilette. ein mann geht zur toilette. die kabine, auch die kabine. ein mann schließt die tür und ein anderer mann ist schon drin. es gibt noch mehr kabinen und trübes licht. ein paar hände fangen bei den hinterbacken an und reiben über den rücken, ziehen das unterhemd heraus bis zu den schultern. das andere paar hände stemmt sich gegen den körper und die kraft des anderen. es müsste alles schnell gehen. er kommt herein. ein mann kommt in eine andere kabine. verschlossen ein körper, doch offen dieser hier. das licht scheint weiter, als ob es den atem anhielte.

holz

das holz ist schon kein holz mehr

holz überall

und holz im wind

derjenige,

der zur toilette geht, der drinnen das sonnenlicht mit dem licht der

neonröhre verwechselt. kein interesse daran, sich damit aufzuhalten,

eins vom anderen zu unterscheiden. er setzt sich auf die toilette: er

hat alle zeit der welt. der hellsichtige und jener, dem ein licht wie

das andere gilt. er verwechselt erst die hosentaschen, doch dann findet

er sie. er sitzt auf der toilettenschüssel, spannt sich genüsslich an

und löst den schuss aus. vielleicht fällt das licht durch ein fenster,

oder es ist nur die neonröhre. von den ersten, die nach dem schuss

hereinkommen, wird sicher einer den eimer und putzlappen holen.

Eduard Escoffet (Barcelona, 29 mei 1979)

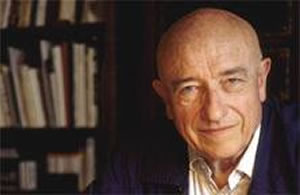

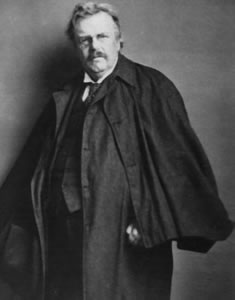

De Engelse dichter, letterkundige, schrijver en journalist Gilbert Keith Chesterton werd geboren in Londen op 29 mei 1874. Zie ook alle tags voor G. K. Chesterton op dit blog.

Uit: Twelve Modern Apostles and Their Creeds

“The difficulty of explaining “why I am a Catholic” is that there are ten thousand reasons all amounting to one reason: that Catholicism is true. I could fill all my space with separate sentences each beginning with the words, “It is the only thing that…” As, for instance, (1) It is the only thing that really prevents a sin from being a secret. (2) It is the only thing in which the superior cannot be superior; in the sense of supercilious. (3) It is the only thing that frees a man from the degrading slavery of being a child of his age. (4) It is the only thing that talks as if it were the truth; as if it were a real messenger refusing to tamper with a real message. (5) It is the only type of Christianity that really contains every type of man; even the respectable man. (6) It is the only large attempt to change the world from the inside; working through wills and not laws; and so on.

Or I might treat the matter personally and describe my own conversion; but I happen to have a strong feeling that this method makes the business look much smaller than it really is. Numbers of much better men have been sincerely converted to much worse religions. I would much prefer to attempt to say here of the Catholic Church precisely the things that cannot be said even of its very respectable rivals. In short, I would say chiefly of the Catholic Church that it is catholic. I would rather try to suggest that it is not only larger than me, but larger than anything in the world; that it is indeed larger than the world. But since in this short space I can only take a section, I will consider it in its capacity of a guardian of the truth.

The other day a well-known writer, otherwise quite well-informed, said that the Catholic Church is always the enemy of new ideas. It probably did not occur to him that his own remark was not exactly in the nature of a new idea. It is one of the notions that Catholics have to be continually refuting, because it is such a very old idea. Indeed, those who complain that Catholicism cannot say anything new, seldom think it necessary to say anything new about Catholicism. As a matter of fact, a real study of history will show it to be curiously contrary to the fact. In so far as the ideas really are ideas, and in so far as any such ideas can be new, Catholics have continually suffered through supporting them when they were really new; when they were much too new to find any other support. The Catholic was not only first in the field but alone in the field; and there was as yet nobody to understand what he had found there.”

G. K. Chesterton (29 mei 1874 – 14 juli 1936)

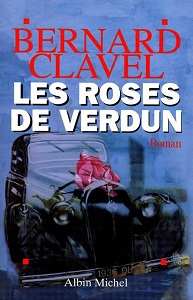

De Franse schrijver Bernard Charles Henri Clavel werd geboren op 29 mei 1923 in Lons-le-Saunier. Zie ook alle tags voor Bernard Clavel op dit blog.

Uit: Les roses de Verdun

« Et

vous partiez à pied ? — On se regroupait par bataillons dans les

prairies où il n’y avait plus un poil d’herbe. La poussière ou le

bourbier. On nous distribuait la soupe ou le café et du pain souvent

moisi. On mangeait debout, à côté des faisceaux. Et puis on partait,

puis après on attendait la nuit pour s’enfiler dans les boyaux d’accès.

On peut dire que la guerre commençait vraiment sur cette route. — Laisse

Augustin parler. Tu dis assez parle pas. Sans se retourner, femme : —

Ça n’est pas tous les jours que je roule sur la Voie sacrée. Si ça ne te

fait aucun effet, tant mieux pour toi… moi, ça me remue. Il a cessé

de m’interroger. Je préférais, car la route n’était vraiment pas facile

et, dans les descentes, la voiture chassait un peu. Plusieurs fois, nous

avons vu des véhicules arrêtés et qui nous gênaient pour passer. Un

gros camion était couché dans le fossé. Non, Monsieur ne m’a plus

interrogé, mais c’est lui qui s’est mis à parler. Il ne l’avait jamais

fait de cette manière, et j’ai compris ce conduire. Ne le fais pas qu’un

bon chauffeur ne le patron a lancé à sa matin-là que s’il m’avait si

souvent interrogé, il avait dû beaucoup lire aussi et regarder souvent

des images de cette partie de la Grande Guerre. Il connaissait les noms

des villages où l’on s’était beaucoup battu. En fait, il nous parlait

comme s’il avait voulu nous apprendre la vérité sur ces combats. Il

disait, par exemple : — Au Tourniquet, quand les poilus regar-daient

s’en aller les camions vides, tous se demandaient combien d’entre eux

revien-draient. Lesquels étaient d’avance marqués pour rester dans ce

bourbier que tant d’autres avaient déjà arrosé de sang. Jusqu’à

Bar-le-Duc, il n’a guère cessé de raconter. Il se souvenait de mille

détails que j’avais oubliés. Même les noms des généraux et des colonels

qui avaient commandé à Ver-dun lui étaient familiers. Et toujours

revenait la grande aventure des camions se suivant à se toucher et de

cette route où des centaines de territoriaux jetaient des pierres à

longueur de journées et de nuits sans jamais inter-rompre ni même

ralentir le trafic. Qu’un camion tombe en panne, il était aussitôt

poussé hors de la chaussée. Jamais, jamais le flot ne devait se

ralentir. A un moment, il a dit : — Cette route, c’était une artère. »

Bernard Clavel (29 mei 1923 – 5 oktober 2010)

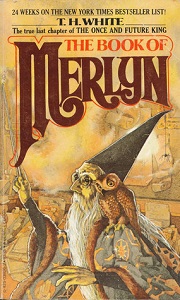

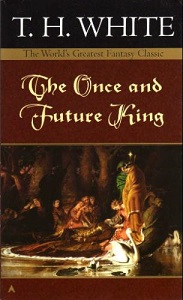

De Engelse dichter en schrijver Terence Hanbury White werd geboren op 29 mei 1906 in Bombay (Mombai). Zie ook alle tags voor T. H. White op dit blog.

Uit: The Once and Future King

“The

day for the ceremony drew near, the invitations to King Pellinore and

Sir Grummore were sent out, and the Wart withdrew himself more and more

into the kitchen. “Come on, Wart, old boy,” said Sir Ector ruefully. “I

didn’t think you would take it so bad. It doesn’t become you to do this

sulkin’.” “I am not sulking,” said the Wart. “I don’t mind a bit and I

am very glad that Kay is going to be a knight. Please don’t think I am

sulking.” “You are a good boy,” said Sir Ector. “I know you’re not

sulkin’ really, but do cheer up. Kay isn’t such a bad stick, you know,

in his way. “Kay is a splendid chap,” said the Wart. “Only I was not

happy because he did not seem to want to go hawking or anything, with

me, any more.” “It is his youthfulness,” said Sir Ector. “It will all

clear up.” “I am sure it will,” said the Wart. “It is only that he does

not want me to go with him, just at the moment. And so, of course, I

don’t go. “But I will go,” added the Wart. “As soon as he commands me, I

will do exactly what he says. Honestly, I think Kay is a good person,

and I was not sulking a bit.” “You have a glass of this canary,” said

Sir Ector, “and go and see if old Merlyn can’t cheer you up.” “Sir Ector

has given me a glass of canary,” said the Wart, “and sent me to see if

you can’t cheer me up.” “Sir Ector,” said Merlyn, “is a wise man.”

“Well,” said the Wart, “what about it?” “The best thing for being sad,”

replied Merlyn, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That

is the only thing that never fails. You may grow old and trembling in

your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of

your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you

devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers

of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then—to learn. Learn why

the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind

can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or

distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

T. H. White (29 mei 1906 – 17 januari 1964)

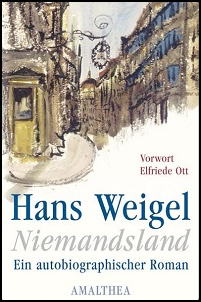

Cover

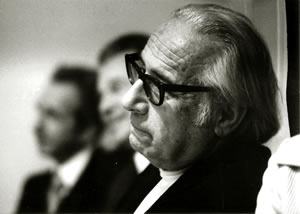

De Oostenrijkse schrijver en theatercriticus Hans Weigel werd geboren op 29 mei 1908 in Wenen. Zie ook alle tags voor Hans Weigel op dit blog.

Uit:Ich war einmal (Biografie)

„Die

Hoffnung vieler Wiener Juden, durch Assimilation Integration zu

erreichen, war in der jüdischen Mittelschicht Wiens am Beginn des

vorigen Jahrhunderts weit verbreitet. Geradezu exemplarisch zeigte sich

diese — wie sich leidvoll herausgestellt hat — Illusion bei Hans Weigels

Eltern. Sein Vater Eduard, ältestes Kind von Lazar Weigl und seiner

Frau Babette, 1874 in Markt Eisenstein, einem kleinen böhmischen Ort

nahe der bayrischen Grenze, geboren, kam schon in den Neunzigerjahren

des 19. Jahrhunderts in die Residenzstadt der Monarchie. In Eisenstein,

dem heutigen ZeleZnä Ruda, lebten nur zwei jüdische Familien, die als

Kaufleute ihr Fortkommen hatten. Lazar Weigl, sein Sohn Eduard fügte

erst in den 1920er-Jahren in Wien das „e” in den Namen „Weigl” ein,

besaß nicht nur eine Gemischtwarenhandlung, „den Laden”, wie er genannt

wurde, sondern auch Felder und Wiesen und führte eine kleine

Milchwirtschaft. Er lebte streng nach den jüdischen Gebräuchen: „[…]

in seinem Haus wurde koscher gekocht, Geschirr und Besteck für Fleisch

und ‚Milchiges’ getrennt — es wurde kein Schweinefleisch zubereitet.”1

Dieser Großvater Lazar, Ludwig, „war ein verständiger, recht kluger

Mann, der auch Humor hatte. […] Ich hatte ihn sehr gern, er war stolz

auf mich, wie auf seinen Sohn Eduard, der es in Wien weit gebracht

hatte”2, als Handelsakademiker bei der Glasfabrik Stölzle, bei der er

seine berufliche Laufbahn begonnen hatte und bei der er zuerst als

Prokurist und dann als Direktor Karriere machte. So schrieb Hans Weigel

in seiner 2008 posthum von seiner Lektorin Elke Vujica herausgegebenen

Autobiografie In die weite Welt hinein, in der er sein Leben von 1908

bis 1938 behandelte. Eduard hatte drei jüngere Schwestern: die Älteste,

Franziska, genannt Fanni, hatte fünf Kinder: Ernst, Otto, Klara, Emma

und Hedwig. Hans Weigel war in den Ferien seiner Volksschulzeit gerne

bei ihnen in Chotieschau (Chotä§ov). Die Mittlere lebte mit ihrem Mann

Robert Abeles und ihrer Tochter Irma in Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary), während

Regine, die Jüngste, mit ihrem Mann Emil Siller in Eisenstein blieb,

zwei Töchter, Roselle und Mitzi, hatte und mit ihrem Mann das Geschäft

von Lazar Weigl übernahm. Der Großvater von Hans Weigel

mütterlicherseits, Julius Fekete, war Kaufmann aus dem ungarischen Gyon,

heute Dabas, und kam mit seiner Frau Katarina, geborene Boskowitz,

schon vor der Jahrhundertwende nach Wien. Sie wohnten in Margareten, dem

5. Wiener Gemeindebezirk, und führten in der nahe gelegenen

Schönbrunner Straße 31 das „Zentralversandhaus Julius Fekete”, einen

Gemischtwarenhandel. Sie waren typische Vertreter des liberalen

jüdischen Bildungsbürgertums, hatten drei Söhne und zwei Töchter. Hugo

übernahm als Ältester, der Not gehorchend, das Zentralversandhaus, da

sein Vater 1903 mit nicht einmal fünfzig Jahren verstorben war. „Onkel

Hugo musste das Geschäft führen, und das war wohl tragisch, denn er war

sehr musikalisch, spielte großartig Klavier, war charmant und witzig und

hatte gewiß ein unerfülltes Leben. Er mochte mich sehr gern, manchmal

saß ich neben ihm, wenn er am Klavier improvisierte.”2 Albert, der

mittlere der drei Söhne, lebte als Ingenieur bei den Saurer-Werken in

Arbon am Bodensee in der Schweiz. „Der dritte Bruder war Onkel Theo,

klein und rundlich, er spielte Geige und war angestellt bei der

Filmfirma Projektograph. Er schwärmte von der neuartigen Erfindung und

prophezeite ihr eine große Zukunft — und wurde in der Familie nur

belächelt.”

Hans Weigel (29 mei 1908 – 12 augustus 1991)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Max Brand (eig. Frederick Schiller Faust) werd geboren op 29 mei 1892 in Seattle. Zie ook alle tags voor Max Brand op dit blog.

Uit: The Garden of Eden

“Can’t

we walk?” suggested Ben Connor, looking up and down the street at the

dozen sprawling frame houses; but the fat man stared at him with calm

pity. He was so fat and so good-natured that even Ben Connor did not

impress him greatly.

“Maybe

you think this is Lukin?” he asked. When the other raised his heavy

black eyebrows he explained: “This ain’t nothing but Lukin Junction.

Lukin is clear round the hill. Climb in, Mr. Connor.”

Connor

laid one hand on the back of the seat, and with a surge of his strong

shoulders leaped easily into his place; the fat man noted this with a

roll of his little eyes, and then took his own place, the old wagon

careening toward him as he mounted the step. He sat with his right foot

dangling over the side of the buckboard, and a plump shoulder turned

fairly upon his passenger so that when he spoke he had to throw his head

and jerk out the words; but this was apparently his time-honored

position in the wagon, and he did not care to vary it for the sake of

conversation. A flap of the loose reins set the horses jog-trotting out

of Lukin Junction down a gulch which aimed at the side of an enormous

mountain, naked, with no sign of a village or even a single shack among

its rocks. Other peaks crowded close on the right and left, with a

loftier range behind, running up to scattered summits white with snow

and blue with distance. The shadows of the late afternoon were thick as

fog in the gulch, and all the lower mountains were already dim so that

the snow-peaks in the distance seemed as detached, and high as clouds.

Ben Connor sat with his cane between his knees and his hands draped over

its amber head and watched those shining places until the fat man

heaved his head over his shoulder.

“Most

like somebody told you about Townsend’s Hotel?” His passenger moved his

attention from the mountain to his companion. He was so leisurely about

it that it seemed he had not heard.

“Yes,” he said, “I was told of the place.” “Who?” said the other expectantly. “A friend of mine.”

The

fat man grunted and worked his head around so far that a great wrinkle

rolled up his neck close to his ear. He looked into the eye of the

stranger.

“Me being Jack Townsend, I’m sort of interested to know things like that; the ones that like my place and them that don’t.”

De Amerikaanse dichter, schrijver en publicist Joel Benton werd geboren op 29 mei 1832 in het kleine stadje Amenia, in county New York. Zie ook alle tags voor Joel Benton op dit blog.

Grover Cleveland

Bring cypress, rosemary and rue

For him who kept his rudder true;

Who held to right the people’s will,

And for whose foes we love him still.

A man of Plutarch’s marble mould,

Of virtues strong and manifold,

Who spurned the incense of the hour,

And made the nation’s weal his dower.

His sturdy, rugged sense of right

Put selfish purpose out of sight;

Slowly he thought, but long and well,

With temper imperturbable.

Bring cypress, rosemary and rue

For him who kept his rudder true;

Who went at dawn to that high star

Where Washington and Lincoln are.

Joel Benton (29 mei 1832 – 15 september 1911)

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata

De Mexicaanse dichteres en journaliste Dolores Dorantes werd in 1973 geboren in Veracruz aan de Golf van Mexico. Zie ook alle tags voor Dolores Dorantes op dit blog.

Give us a bottle and let’s be done with your world

Give

us a bottle and let’s be done with your world. Light us and the fire

will spread like a plague. We arrive at your office. At your machine. We

arrive at your masterful chair. At that world that is no longer the

world. Where nothing touches and we kiss each other. We join our girlish

lips damp with some kind of fuel. Give us a forest. Give us the

presidency.

This book does not exist

This

book does not exist. All that has been said in the name of a love that

does not last. Each line dispossessed. The drug that seeing blood has

become. Open us in this impossible territory. Unlimited. Repeated.

Uncovered. We are here as the trace of a code. We knock on your door for

you to swim us. Fire and water. We are inside bottles and explosives.

We are extermination. Place without country. Tie us up, put a leash on

us. Command us to get out and show me your tongue: a gust of birds.

Dolores Dorantes (Veracruz, 1973)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 29e mei ook mijn blog van 29 mei 2018 en ook mijn blog van 29 mei 2016 deel 2.