Onafhankelijk van geboortedata

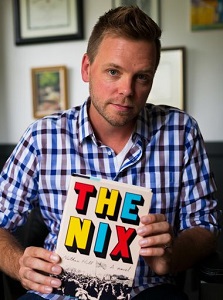

De Amerikaanse schrijver Nathan Hill werd geboren in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1976 en groeide op in het Middenwesten, waar zijn grootouders als maïs-, soja- en veeboeren hadden gewerkt. Zijn familie verhuisde voortdurend toen hij opgroeide – naar Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma en Kansas – terwijl zijn vader zich omhoog werkte naar het management bij Kmart. Boeken waren schaars bij hem thuis, maar zijn ouders verwenden hem met de Choose Your Own Adventure series. Vanaf de lagere school wilde Hill schrijver worden. In de tweede klas, schreef hij een verhaal over een dappere ridder proberen om een prinses te redden uit een spookkasteel: “The Castle of No Return” en hij illustreerde het zelf. Hij studeerde Engels en journalistiek aan de Universiteit van Iowa, waar hij studeerde bij de schrijfster Sara Levine. Hill probeerde de journalistiek voor een tijdje door te schrijven voor The Cedar Rapids Gazette, toen ging terug naar de University of Massachusetts, Amherst voor zijn M.F.A. aan. Hij publiceerde verhalen in een handvol bekende tijdschriften als The Iowa Review, Agni en The Gettysburg Review. Maar doorbreken in de New Yorkse literaire wereld was zwaarder dan hij had verwacht. Zijn verhalenbundel werd afgewezen door 38 literaire agenten. Toen de afwijzingen zich opstapelden begon Hill te wanhopen. Om zichzelf af te leiden, begon hij met het spelen van World of Warcraft, die al snel een obsessie werd. Hij stopte na een paar jaar met spelen en begon zich meer te richten op het schrijven en onderzoek doen voor “The Nix”, een rommelig proces dat hij beschreef als “drie jaar van schrijven, zes jaar van onderzoek en ploeteren” Tegenwoordig werkt Hill als Associate Professor Engels aan de Universiteit van St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, waar hij creatief schrijven doceert en literatuurcursussen geeft.

Uit: The Nix

“Late Summer 1988

If Samuel had known his mother was leaving, he might have paid more attention. He might have listened more carefully to her, observed her more closely, written certain crucial things down. Maybe he could have acted differently, spoken differently, been a different person.

Maybe he could have been a child worth sticking around for.

But Samuel did not know his mother was leaving. He did not know she had been leaving for many months now—in secret, and in pieces. She had been removing items from the house one by one. A single dress from her closet. Then a lone photo from the album. A fork from the silverware drawer. A quilt from under the bed. Every week, she took something new. A sweater. A pair of shoes. A Christmas ornament. A book. Slowly, her presence in the house grew thinner.

She’d been at it almost a year when Samuel and his father began to sense something, a sort of instability, a puzzling and disturbing and some-times even sinister feeling of depletion. It struck them at odd moments. They looked at the bookshelf and thought: Don’t we own more books than that? They walked by the china cabinet and felt sure something was missing. But what? They could not give it a name—this impression that life’s details were being reorganized. They didn’t understand that the reason they were no longer eating Crock-Pot meals was that the Crock-Pot was no longer in the house. If the bookshelf seemed bare, it was because she had pruned it of its poetry. If the china cabinet seemed a little vacant, it was because two plates, two bowls, and a teapot had been lifted from the collection.

They were being burglarized at a very slow pace.

“Didn’t there used to be more photos on that wall?” Samuel’s father said, standing at the foot of the stairs, squinting. “Didn’t we have that picture from the Grand Canyon up there?”

“No,” Samuel’s mother said. “We put that picture away.”

“We did? I don’t remember that.”

“It was your decision.”

Nathan Hill (Cedar Rapids, 1976)