De Brits-Amerikaanse schrijver Christopher Isherwood werd geboren op 26 augustus 1904 in Disley in het graafschap Cheshire in Engeland. Zie ook alle tags voor Christopher Isherwood op dit blog.

Uit: Christopher and His Kind

« The train moved on again. For the first time in his life, he found himself entering a foreign country without official permission. If Heinz had been with him, what could the lawyer have done but accept the accomplished fact and somehow arrange for Heinz to remain in Belgium?

Next morning, the lawyer left Brussels by car for Trier, as he had promised. That night he returned, alone. He told Christopher that he had duly met Heinz at the hotel. Heinz had assured him that he hadn’t been questioned, hadn’t aroused anybody’s curiosity. They had gone to the consulate and got the visa. Then, just as they were about to start on their return journey, some Gestapo agents had appeared. They had asked to see Heinz’s papers and had then taken him away with them. They had told the lawyer that Heinz was under arrest as a draft evader. Before leaving Trier, the lawyer had consulted a German lawyer and engaged him to defend Heinz at his forthcoming trial.

A day or two after the arrest, the German lawyer came from Trier to Brussels to discuss the tactics of Heinz’s defense. He was a Nazi Party member in good standing and had the boundless cynicism of one who is determined to survive under any conceivable political conditions. Christopher, in his present hyper-emotional state, found a strange relief in talking to him, because he seemed utterly incapable of sympathy. Heinz was now in four kinds of potential trouble: He had attempted to change his nationality. (This could almost certainly be concealed from the prosecution.) He had consorted with a number of prominent anti-Nazis, most of them Jews. (This could probably be concealed or, at worst, excused as having been Christopher’s fault.) He had been guilty of homosexual acts. (This couldn’t be co-directors that what they need is the spirit of the merchant-adventurers. He hates the banks. He hates public companies, because they aren’t allowed to take risks. He particularly enjoys ragging the pompous U.S.A. businessmen. Somebody once cabled him from New York: ‘Believe market has touched bottom.’ Potter cabled back: `Whose?’ At board meetings he lies on a sofa—ostensibly because he once had a bad leg; actually because this position gives him a moral advantage. He and his colleagues tell each other dirty limericks and the very serious-minded secretary takes them all down in shorthand—because, as he once explained, he thought they might be in code.

Much less willingly, Wystan and Christopher also became the captive audience of a young man with whom they had to share their table in the second-class dining room. He was a rubber planter, returning from leave in England to a plantation near Singapore. I will call him White.“

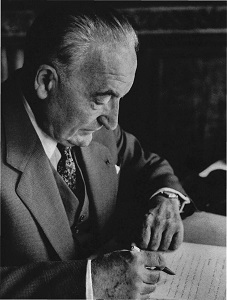

Christopher Isherwood (26 augustus 1904 – 4 januari 1986)

Scene uit de gelijknamige tv-film uit 2011