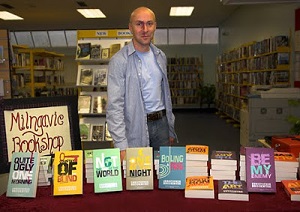

De Schotse schrijver Christopher Brookmyre werd geboren op 6 september 1968 in Glasgow. Zie ook alle tags voor Christopher Brookmyre op dit blog.

Uit: Be My Enemy

“`Bin Laden? A fucking charlatan.’ ‘Be serious for a minute,’ Williams told him. ‘I am being serious. That’s my point. Everybody’s so reverent about this guy. Strip away all the mythologising and hocus-pocus and what have you got? Patty Hearst with a beard. Bored rich kid playing at soldiers. He’s in the huff with his family, for Christ’s sake — the psychology’s pitifully mundane. If he’d been born into a semi in Surbiton he’d have painted his bedroom black, got himself a Nine Inch Nails T-shirt and hung around swingparks drinking cider from plastic bottles.’ Fotheringham’s rant was attracting admonitory glances, more in disapproval of the growing volume and vehemence than the content, which wouldn’t have been clearly discernible above the whipping wind. Raised voices were not decorous at a funeral; they suggested that your thoughts were not respectfully concentrated upon the memory of the departed, even if, in Williams’s case, that was not strictly true. Nothing was more prominent in his mind than the man they had just buried or the consequences of his loss, not least the fact that Williams now had his job. Fotheringham gestured apologetic acknowledgement and Williams led him in the opposite direction to the dispersing mourners. `Bin Laden’s about a lot more than thrill kills and power trips,’ Williams chided, measuring his condescension precisely. ‘And there’s three thousand dead people in New York of the opinion that you should be taking him more seriously.’ ‘I’m taking him entirely seriously, sir. I just don’t think it will help us if we buy into the hype and start thinking of him as some kind of formidable genius. Look at the Black Spirit, if you need a primer. Remember what a bogeyman he was? Turned out to be a fucking oil-biz wage slave from Aberdeen.’ `Quite. Something, I should remind you, that we only learned after the fact. Didn’t make him any easier to catch, did it? And besides, I don’t think there’s much ground for comparison. For all his theatrics, the Black Spirit was essentially just a mercenary, prepared to do horrific things on other people’s behalf if they paid him enough. Bin Laden represents the possibility of ten thousand Black Spirits, all of them prepared to do horrific things merely because it’s Allah’s bidding. We’ve never had to face this kind of fanaticism before: there’s no fifth column to cultivate, no disaffected factions to encourage, no waverers, not even anyone we can bribe and corrupt. Just total, unquestioning, homicidal, suicidal commitment to the cause.’ `With respect, sir, that’s what I mean by believing the hype. For one thing, there is no cause. Bin Laden’s too smart to marry himself to anything as cumbersome as a coherent or even consistent political ideology, because such a thing could be debated, held up to scrutiny, and, worst of all, alienate potential followers. “The cause of Islam” is expediently nebulous.”

Christopher Brookmyre (Glasgow, 6 september 1968)