De Nederlandse dichter, vertaler en journalist Jan Eijkelboom werd op 1 maart 1926 in Ridderkerk geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Jan Eijkelboom op dit blog.

Camping, Frankrijk

Voor het eerst dat ik sliep in een tent,

voor het eerst naar een ruisen geluisterd

dat voor het ruisen van regen,

het vallen van regen te zacht was

en ook voor de wind te gelijk, te gelijk aan zichzelf.

En ’s ochtends gezien hoe water

bijna rechtstandig,

toch zonder te breken, naar lager

water kan gaan, onzichtbaar verschietend.

Hadden wij zo kunnen leven,

zo blijven leven als toen

in die tent, in dat gras

Geen woede, geen andere hartstocht,

geen weten wie zo stil overstroomt

in wie.

Ik liep in een straat

Ik liep in een straat

die doodliep,

op het spoor van iemand

die hier gelopen had

maar die nu dood was.

In kieren tussen de keien

groeide fris gras

want doodlopende straten

bieden meer levenskans

dan straten die doorlopen

naar mensen die

nog volop leven.

Een ijzersterke mist

Eerste najaarsnevel boven de sloot

tussen spoorbaan en snelweg

en heel dat doen alsof

wordt nu het zwijgen opgelegd.

Het lijkt blijvend door afwezigheid

van wind. Het is ijl en standvastig.

Waarom trekt dit versterven meer

dan bloesemtak of eerste sneeuw?

Alle begin verheldert, roept beelden op

van eerdere aanvang die te snel verliep

om dicht te slibben, tijdstippen

met de gedegen zwaarte van een eeuw.

Maar deze nevel laat geen modder na,

wekt geen verwachting, lost slechts op

en laat toch in ’t voorbijgaan weten

dat wij nog niet, nog lange niet

zijn uitgekeken.

Jan Eijkelboom (1 maart 1926 – 28 februari 2008)

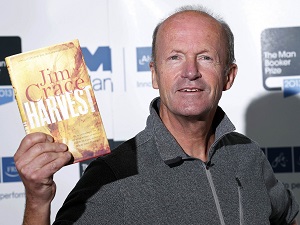

De Engelse schrijver Jim Crace werd geboren op 1 maart 1946 in St. Albans, Hertfordshire. Zie ook alle tags voor Jim Crace op dit blog.

Uit: Harvest

“Now that we have reached our master’s paddocks and his garths, we can smell and taste the straw. The smoke and flames are coming not from his home but from his hay lofts and his stable roofs. His pretty, painted dovecote has already gone. We expect to spot his home- birds’ snowy wings against the smoke- gray sky. But there are none.

I know at once whom we should blame. When Christopher and Thomas Derby, our only twins, and Brooker Higgs came back from wooding last evening, they seemed a little too well satisfied, but they weren’t bringing with them any fowl or rabbit for the pot, or even any fuel. Their only spoils, so far as I could tell, were a bulky, almost weightless sack and immodest fits of laughter. They’d been mushrooming. And by the looks of them they had already eaten raw some of the fairy caps they’d found. I did the same myself in my first summer of settlement here, a dozen or so years ago, when I was greener and less timid, though not young. I remember eating them. They are beyond forgetting. Just as yesterday, the last sheaf of that year’s harvest had been cut and stood. And, just as today, we’d faced a break from labor, which meant that I could sleep my mischief off. So in the company of John Carr, my new neighbor then, my neighbor still, I went off that afternoon to Thank the Lord for His Munificence by hunting fairy caps in these same woods. I’ll not forget the dancing lights, the rippling and the merriment, the halos and the melting trails that followed anything that moved, the enormous fearlessness I felt, the lasting fear (yes, even now), or how darkly blue the moon became that night, and then how red. I wish I’d had the courage since to try to find that moon again.

Last evening, when the twins and Brooker Higgs jaunted past our cottages and waved at us with gill stains on their fingertips, I asked these merry men, “Had any luck?” They bared their sack of spoils at once, because they were too foxed and stupefied to conceal them, even though they understood my ancient closeness to the manor house. I pulled aside the dampening of leaves and inspected their few remaining fairy caps, saved for later revels, I suppose, plus a good number of golden shawls, which, stewed in milk and placed inside a dead man’s mouth, are meant to taste so good they’ll jolt him back to life. Accounting for the bulk of their sack was a giant moonball, its soft, kid- leather skin already smoking spores, and far too yellowy and dry to cook. Why had they picked it, then? Why hadn’t they just given it a satisfying kick? What kind of wayward lads were these?”

Jim Crace (St. Albans, 1 maart 1946)

De Franse schrijfster en filmmaakster Delphine de Vigan werd geboren op 1 maart 1966 in Boulogne-Billancourt. Zie ook alle tags voor Delphine de Vigan op dit blog.

Uit:No et moi

“Je donnerais tout, mes livres, mes encyclopédies, mes vêtements, mon ordinateur, pour qu’elle ait une vraie vie, avec un lit, une maison et des parents pour l’attendre. Je pense à l’égalité, à la fraternité, à tous ces trucs qu’on apprend à l’école et qui n’existent pas. On ne devrait pas faire croire aux gens qu’ils peuvent être égaux ni ici ni ailleurs. Ma mère a raison. C’est la vie qui est injuste et il n’y a rien à ajouter. Ma mère sait quelque chose qu’on ne devrait pas savoir. C’est pour ça qu’elle est inapte pour son travail, c’est marqué sur ses papiers de sécurité sociale, elle sait quelque chose qui l’empêche de vivre, quelque chose qu’on devrait savoir seulement quand on est très vieux. On apprend à trouver des inconnues dans les équations, tracer des droites équidistantes et démontrer des théorèmes, mais dans la vraie vie, il n’y a rien à poser, à calculer, à deviner. C’est comme la mort des bébés. C’est du chagrin et puis c’est tout. Un grand chagrin qui ne se dissout pas dans l’eau, ni dans l’air, un genre de composant solide qui résiste à tout. »

(…)

” … Il y a cette ville invisible, au coeur même de la ville. Cette femme qui dort chaque nuit au même endroit, avec son duvet et des sacs. À même le trottoir. Ces hommes sous les ponts, dans les gares, ces gens allongés sur des cartons ou recroquevillés sur un banc. Un jour, on commence à les voir. Dans la rue, dans le métro. Pas seulement ceux qui font la manche. Ceux qui se cachent. On repère leur démarche, leur veste déformée, leur pull troué. Un jour on s’attache à une silhouette, à une personne, on pose des questions, on essaie de trouver des raisons, des explications, et puis on compte. Les autres, des milliers. Comme le symptôme de notre monde de malade. Les choses sont ce qu’elle sont. Mais moi je crois qu’il faut garder les yeux grand ouverts. Pour commencer.”

Delphine de Vigan (Boulogne-Billancourt, 1 maart 1966)

De Zwitserse dichter, schrijver, cabaretier en liedjesmaker Franz Hohler werd geboren op 1 maart 1943 in Biel. Zie ook alle tags voor Franz Hohler op dit blog

Weiss noch jemand

Weiss noch jemand

wo das Denkmal stand

für die Prinzessin

aus dem Morgenland

die mit dem Sternenmantel

durch die Wälder ritt

bevor der grosse Krieg

darüber schritt?

Weiss noch jemand

wo der Garten war

mit den Sommergästen

und der Kinderschar

auf den der Mond

in verzauberten Nächten schien

und den die Eule besuchte

und der Hermelin?

Weiss noch jemand

wo der Geiger blieb

der uns zu ausgelassenen

Tänzen trieb

mit seinen kühnen Läufen

und der schmelzenden Terz?

Er weckte die Sehnsucht

und brach uns das Herz.

Weiss noch jemand

wo der Grabstein ist

auf dem der Todesengel

den König küsst

und ihn so fest

in seinen Armen hält

dass ihm die Krone

vor die Füsse fällt?

Weiss noch jemand

wo der Wildbach floss

im Bergwald mit dem

Raubritterschloss

aus dessen Wasser

die weisse Schlange trank

bevor sie im eisigen

Stausee versank?

Weiss noch jemand

wie die Inschrift hiess

die man fand

im dunklen Kellerverlies

in dem der Zar so schmählich

zu Tode kam

und man der ganzen Familie

das Leben nahm?

Weiss noch jemand

wie das Volkslied geht

in dem das Mädchen am Morgen

am Fenster steht

und die Fahne in der Ferne

flattern sieht

hinter der sein Liebster

zum Kampfe zieht?

Prinzessin und Geiger

König und Zar

Schloss und Schlange

und Kinderschar

die Gärten – was ist nur

mit ihnen geschehn

und dem Burschen und dem Mädchen

die sich nie wieder sehn?

Franz Hohler (Biel, 1 maart 1943)

De Britse schrijver Giles Lytton Strachey werd geboren op 1 maart 1880 in Londen. Zie ook alle tags voor Lytton Strachey op dit blog.

Uit: Queen Victoria

“Victoria understood very well the meaning and the attractions of power and property, and in such learning the English nation, too, had grown to be more and more proficient. During the last fifteen years of the reign — for the short Liberal Administration of 1892 was a mere interlude imperialism was the dominant creed of the country. It was Victoria’s as well. In this direction, if in no other, she had allowed her mind to develop. Under Disraeli’s tutelage the British Dominions over the seas had come to mean much more to her than ever before, and, in particular, she had grown enamoured of the East. The thought of India fascinated her; she set to, and learnt a little Hindustani; she engaged some Indian servants, who became her inseparable attendants, and one of whom, Munshi Abdul Karim, eventually almost succeeded to the position which had once been John Brown’s. At the same time, the imperialist temper of the nation invested her office with a new significance exactly harmonising with her own inmost proclivities. The English polity was in the main a common-sense structure, but there was always a corner in it where common-sense could not enter — where, somehow or other, the ordinary measurements were not applicable and the ordinary rules did not apply. So our ancestors had laid it down, giving scope, in their wisdom, to that mystical element which, as it seems, can never quite be eradicated from the affairs of men. Naturally it was in the Crown that the mysticism of the English polity was concentrated — the Crown,with its venerable antiquity, its sacred associations, its imposing spectacular array. But, for nearly two centuries, common-sense had been predominant in the great building, and the little, unexplored, inexplicable corner had attracted small attention. Then, with the rise of imperialism,there was a change. For imperialism is a faith as well as a business; as it grew, the mysticism in English public life grew with it; and simultaneously a new importance began to attach to the Crown. The need for a symbol — a symbol of England’s might, of England’s worth, of England’s extraordinary and mysterious destiny — became felt more urgently than ever before. The Crown was that symbol: and the Crown rested upon the head of Victoria. Thus it happened that while by the end of the reign the power of the sovereign had appreciably diminished, the prestige of the sovereign had enormously grown.”

Lytton Strachey (1 maart 1880 – 21 januari 1932)

The Mill at Tidmarsh, 1918. Een schilderij van Dora Carrington van de “Mill House”, Tidmarsh, Pangbourne, op de Upper Thames, waar veel van “Queen Victoria”werd geschreven.

De Amerikaanse dichter Robert Traill Spence Lowell werd geboren op 1 maart 1917 in Boston. Zie ook alle tags voor Robert Lowell op dit blog.

Water

It was a Maine lobster town—

each morning boatloads of hands

pushed off for granite

quarries on the islands,

and left dozens of bleak

white frame houses stuck

like oyster shells

on a hill of rock,

and below us, the sea lapped

the raw little match-stick

mazes of a weir,

where the fish for bait were trapped.

Remember? We sat on a slab of rock.

From this distance in time

it seems the color

of iris, rotting and turning purpler,

but it was only

the usual gray rock

turning the usual green

when drenched by the sea.

The sea drenched the rock

at our feet all day,

and kept tearing away

flake after flake.

One night you dreamed

you were a mermaid clinging to a wharf-pile,

and trying to pull

off the barnacles with your hands.

We wished our two souls

might return like gulls

to the rock. In the end,

the water was too cold for us.

Robert Lowell (1 maart 1917 – 12 September 1977)

De Nederlandse schrijfster Myrthe van der Meer (pseudoniem) werd geboren op 1 maart 1983 in Den Bosch. Zie ook alle tags voor Myrthe van der Meer op dit blog.

Uit: PAAZ

“Ik staar naar de witte muur tegenover me en probeer mijn hoofd met dezelfde leegte te vullen, maar de gedachten beginnen door mijn hersens te krioelen en veranderen de wereld in een verontrustend grijs. Als ik mijn vingers op het toetsenbord leg, voelt het alsof iedere molecuul in mijn lichaam krijsend zo ver mogelijk bij de computer vandaan probeert te kruipen. Ik klem mijn kiezen op elkaar en mijn vingers kruipen over de toetsen, maar dan is de mail af.

Niet in staat om te werken, ha! Grimmig sluit ik het mailprogramma af. Warrige gedachten beginnen over elkaar heen te buitelen maar ik duw ze weer terug op hun plek. Niet nadenken – vooral niet nadenken! – gewoon doen. Iets doen. Naar het toilet. Als ik de gang in wil lopen, verandert die in een moeras waar ik steeds verder in wegzak. Ik weet met veel moeite langs de muur vooruit te waden, maar als de uitgeefster van het geschiedenisfonds de hoek om komt, spring ik weer in het gelid.

‘Hé, Emma, nog hier? Ik dacht dat je allang weg zou zijn.’

‘Nog drie uur, dan begint de vakantie!’ zeg ik met een schrille lach.

Is dit mijn stem?

‘Volgens mij kun je die wel gebruiken. Ga je nog iets leuks doen?’

‘Helemaal niets,’ antwoord ik met een bravoure die ik niet voel. ‘Slapen, luieren, in de zon liggen en alleen een boek lezen als ik dat zelf wil. Heel saai dus.’

‘Klinkt hemels. Als je maar niet aan de uitgeverij denkt, want het wordt weer een gekkenhuis met de nieuwe aanbiedingscatalogus. Ik zie je hier over vier weken weer – geen moment eerder!’

Myrthe van der Meer (Den Bosch, 1 maart 1983)

De Oostenrijkse schrijver, dichter en schilder Franzobel werd geboren op 1 maart 1967 in Vöcklabruck. Zie ook alle tags voor Franznbel op dit blog.

Uit:Groschens Grab

“Eines sage ich Ihnen gleich, schrie die Frau ins Telefon, mit der Polizei will ich nichts zu tun haben. Nichts! Nur damit das klar ist. Sie müssen dieses Gespräch auch nicht zurückverfolgen, weil ich stehe in einer öffentlichen Telefonzelle … Ja, so etwas gibt es noch!

– Woher haben Sie meine Nummer? Warum rufen Sie nicht im Kommissariat an? Groschen sah auf die Uhr, es war sieben Uhr morgens. Die weibliche Stimme am anderen Ende der Leitung klang heiser und überdreht, so, als ob die Frau nachts nichts geschlafen und sich Mut für diesen Anruf angetrunken hätte.

– Um als Aktennotiz zu landen? Glauben Sie, ich weiß nicht,wie es bei Ihnen zugeht? Die kleinen Beamten würden das als lächerlich abtun. Aber Sie als Kommissar, Sie werden sich darum kümmern. Sie nehmen das ernst.

– Worum geht es denn?

– Entführung! Menschenraub! Am helllichten Tag, gestern um halb fünf in der Klagbaumgasse, sagte die verrauchte, leicht hysterisch klingende Stimme. Ich bin im Rubenspark gesessen … Kennen Sie? Vierter Bezirk, Wirtschaftskammer, Mittersteig, Caritas …

– Ist mir bekannt.

– Da sehe ich eine alte Dame, ich denke mir noch, die ist aber elegant, eine richtige Lady. Plötzlich kommt ein Auto, bremst, bleibt stehen, einer springt heraus und zerrt sie in den Wagen. Sie will schreien, aber der hält ihr den Mund zu.

Sie will sich wehren, aber der ist stärker. Während ich noch überlege, um Hilfe schreien will, rauscht das Auto schon davon. Und das in Wien, wo es immer heißt, hier passiert nichts,

Wien ist sicher. Pha! Da sieht man ja, wie sicher Wien ist.

Sie werden mich jetzt für verrückt halten, aber ich habe die Gewalt gespürt, die Verzweiflung. Das war Kidnapping!“

Franzobel (Vöcklabruck, 1 maart 1967)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Steven Barnes werd geboren op 1 maart 1952 in Los Angeles. Zie ook alle tags voor Steven Barnes op dit blog.

Uit: Lion’s Blood

“This didn’t happen. It was the work of moments to locate the source of the glittering he had glimpsed from above.

Aidan’s heart quickened as his hands closed around his prize. For a moment he floated there, suspended like some strange river creature, the Lady’s strong arms tugging at him, his bare feet clinging to a rock for ballast.

The object that had caught his attention was a knife. Not just any knife, though. Not some fisherman’s blade tumbled overboard, but something wholly alien to his experience.

It was gold, wreathed with gems about its handle, its two-hand length of blade as gently curved as a shark’s tooth. Young Aidan found it so beautiful that he almost forgot the need for breath.

His aching lungs would no longer be denied. Gripping his prize tightly, Aidan released the rock and kicked back toward the sun. Sound and scent and taste inundated him as he held the blade high.

His father’s strong arm clasped his, lifting Aidan from the river with effortless ease. “What have you, boy?”

Aidan panted. His breathlessness owed more to excitement than lack of air. “A knife, Da.” He smoothed his fingers over its surface, tracing every knob and etching. “A golden knife!”

Shadows flitted over Mahon O’Dere’s face. The expression was darker than mere curiosity, but before Aidan could put a name to the shade it was gone. His father stretched out his arm. Reluctantly, Aidan placed the blade in Mahon’s calloused hand.”

Steven Barnes (Los Angeles, 1 maart 1952)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 1e maart ook mijn drie blogs van 1 maart 2015.