De Amerikaanse schrijver John Green werd geboren in Indianapolis, Indiana, op 24 augustus 1977. Zie ook alle tags voor John Green op dit blog.

Uit:The Fault in Our Stars

“Late in the winter of my seventeenth year, my mother decided I was depressed, presumably because I rarely left the house, spent quite a lot of time in bed, read the same book over and over, ate infrequently, and devoted quite a bit of my abundant free time to thinking about death.

Whenever you read a cancer booklet or website or whatever, they always list depression among the side effects of cancer. But, in fact, depression is not a side effect of cancer. Depression is a side effect of dying. (Cancer is also a side effect of dying. Almost everything is, really.) But my mom believed I required treatment, so she took me to see my Regular Doctor Jim, who agreed that I was veritably swimming in a paralyzing and totally clinical depression, and that therefore my meds should be adjusted and also I should attend a weekly Support Group.

This Support Group featured a rotating cast of characters in various states of tumor-driven unwellness. Why did the cast rotate? A side effect of dying.

The Support Group, of course, was depressing as hell. It met every Wednesday in the basement of a stone-walled Episcopal church shaped like a cross. We all sat in a circle right in the middle of the cross, where the two boards would have met, where the heart of Jesus would have been.

I noticed this because Patrick, the Support Group Leader and only person over eighteen in the room, talked about the heart of Jesus every freaking meeting, all about how we, as young cancer survivors, were sitting right in Christ’s very sacred heart and whatever.

So here’s how it went in God’s heart: The six or seven or ten of us walked/wheeled in, grazed at a decrepit selection of cookies and lemonade, sat down in the Circle of Trust, and listened to Patrick recount for the thousandth time his depressingly miserable life story—how he had cancer in his balls and they thought he was going to die but he didn’t die and now here he is, a full-grown adult in a church basement in the 137th nicest city in America, divorced, addicted to video games, mostly friendless, eking out a meager living by exploiting his cancertastic past, slowly working his way toward a master’s degree that will not improve his career prospects, waiting, as we all do, for the sword of Damocles to give him the relief that he escaped lo those many years ago when cancer took both of his nuts but spared what only the most generous soul would call his life.

AND YOU TOO MIGHT BE SO LUCKY!

Then we introduced ourselves: Name. Age. Diagnosis. And how we’re doing today. I’m Hazel, I’d say when they’d get to me. Sixteen. Thyroid originally but with an impressive and long-settled satellite colony in my lungs. And I’m doing okay.”

John Green (Indianapolis, 24 augustus 1977)

De Nederlands-Zwitserse schrijver, tekstschrijver, componist, zanger en pianist Drs. P (eig. Heinz Hermann Polzer) werd geboren in het Zwitserse Thun op 24 augustus 1919. Zie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor Drs. P op dit blog.

Balladette

Het moet niet altijd iets bijzonders zijn

Niet elke keer dat spitse, dat coquette

Leun rustig achterover in uw stoel:

Vandaag een welgeschapen balladette

Geschikt voor pleinterras, boudoir, woestijn…

En niet verkrijgbaar op muziekcassette

Verpozing, zeker, maar geen dolle boel

Vandaag een welgeschapen balladette

Ze hadden me gevraagd om een kwatrijn

Waartegen mijn geweten zich verzette

(Geweten? Laat ons zeggen, eergevoel)

Vandaag een welgeschapen balladette

O lezer/lezeres, nu ik verdwijn –

Besef hoe goed ik het met u bedoel

Vandaag een welgeschapen balladette

De vader van mijn moeder keerde weer

De vader van mijn moeder keerde weer

Van vreemde namen op de wereldkaart

Bepakt, gebruind, vermoeid (dat zag men wel)

En hoeveel goud was eigen haard niet waard!

’t Gezin zat juist aan ’t middagmaal terneer

Het kind sprong op. De ega sprak bedaard

‘Zo, ben je daar, Henri?’ (De tafelschel)

En hoeveel goud was eigen haard niet waard

‘François, nog een couvert hier voor mijnheer’

(Het feit is al geruime tijd verjaard

Ik heb ’t gehoord zoals ik het vertel)

En hoeveel goud was eigen haard niet waard?

Hij was beroemd, bekwaam, een man van eer

Zij dirigeerde ’t huiselijk bestel

En hoe! Veel goud was eigen haard niet waard

De Aarde is een welvoorziene dis

De Aarde is een welvoorziene dis

En ieder krijgt te weinig of te veel

Maar iemand moet de rekening betalen

Het leven is nog steeds geen pijp kaneel

We leren allemaal geschiedenis

De vork zit blijkbaar ergens in de steel

Maar waar de steel is, kan geen mens bepalen

Het leven is nog steeds geen pijp kaneel

We zijn ’t erover eens, er is iets mis

En soms grijpt ons de onmacht naar de keel

Wat is het nut van strijd, van idealen?

Het leven is nog steeds geen pijp kaneel

Bedenk ook, wat een treurig werk dit is

Het schrijven dus van zulke lulverhalen

Het leven is nog steeds geen pijp kaneel

Drs. P (24 augustus 1919 – 13 juni 2015)

De Nederlandse dichteres en schrijfster Marion Bloem werd op 24 augustus 1952 geboren in Arnhem. Zie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor Marion Bloem op dit blog.

Uit:Haar goede hand

“Haar oudste zus, Yola, bemoeide zich er niet mee, evenmin als Boelé, maar zij mocht Han helpen omdat Hon van haar was. Zij noemde hem zo sinds ze had leren praten. Het was geen afkorting, geen verbastering. Ze wist niet beter of dat was de naam van haar eerste hond. Iedereen was zijn vorige vergeten. Han groef een kuil vlak bij de wc van de bediendes. ‘Daar liggen er nog twee,’ had hij gezegd, ‘honden gaan eerder dood dan mensen.’ Raymond was een lopende baby. Hij dacht nog dat je dood was als je in de modder viel en je ogen dichthield. En hij dacht dat dood iets was waaruit je even later op kon staan alsof er niets gebeurd was. Haar broertje was schattig, zoals wanneer hij balanceerde terwijl hij met de aan elkaar gebonden bamboestokken in haar richting wees. Hij porde ermee in haar buik.

Ze weet zeker dat ze bij aankomst Tante en Oom met haar goede hand had begroet. Al herinnert ze zich niet hoe ze na de lange treinreis het tuinpad van Tantes erf op liepen. Als het toen niet gelukt was om haar rechterhand omhoog te brengen, hadden ze het immers meteen gemerkt. Wanneer de arm haar in de steek begon te laten, is voor haar een raadsel. Misschien logeerden ze al twee handen bij Tante, misschien pas zes vingers. Wie nog niet naar school gaat, begrijpt niks van tijd. Voor een kind duurt plezier altijd te kort, verveling te lang, en angst lijkt nooit te stoppen. Angst beklijft. Naderhand vertelde niemand haar de details. Mammie zeker niet. Pappie ook weinig. Yola en Han wel een beetje. Op hun manier. Zij waren net zo goed kinderen. Ook Yola, al moest ze op hen passen. Het kan zijn dat het geen echte herinnering is en dat ze heeft onthouden wat haar oudste broer en grote zus er naderhand over hebben verteld, maar dat denkt ze niet. Het is of haar arm weer net zo wordt als toen en steeds minder kan. Schrijven lukt nauwelijks nog. Over haar handtekening doet ze lang. Gelukkig hoeft ze die niet vaak meer te zetten. Haar kinderen regelen wat zij niet meer kan doen. Toch blijft ze de hand gebruiken. Ze geeft niet op. Als ze van buiten komt, door winterse vorst, herfstkou, lentebuien, zomerse kilte, is de hand tot niets in staat. Ze wrijft de kou eraf, houdt hem onder de warme kraan totdat er weer leven in haar vingers komt. Ze begreep niet waarom ze door haar familie alleen werd gelaten. Haar moeder, met de baby op de arm, kwam geen stap dichterbij. Dat vind je gek als je een peuter bent. Daar blijf je later altijd aan denken. Haar vader mocht wel naast haar liggen. Af en toe. Tante had Pappie een Theresiabeeldje meegegeven. Dat had ze naast zich, in haar bed. Ze heeft het nog steeds. Het is een paar keer gelijmd. Het kwam op 24 december 1950 gebroken uit de scheepskoffer.”

Marion Bloem (Arnhem, 24 augustus 1952)

De Nederlandse schrijver en rapper Pepijn Lanen werd geboren in Utrecht op 4 augustus 1982. Zie ook alle tags voor Pepijn Lanen op dit blog.

Uit: Sjeumig

“En om het allemaal af te maken was in de verte heel zachtjes maar duidelijk het piepen en knarsen van een huifkar te horen, getrokken door een lomp boerenpaard. Het was de symbolische huifkar van een vergeten afspraak. Na nog een minuut of tien over straat slenteren als een menselijke wijnvlek in het witte damast van het leven viel het hem eindelijk allemaal te binnen. ‘CONJO’ schreeuwde hij zowel in het Spaans als in het Nederlands.

Hij keek uit het raam van de taxi naar de voorbij glijdende gevels die op een speelse manier modern en klassiek met elkaar afwisselden. In zijn hoofd woedde een wervelstorm van tijdstippen, adressen, mensen om teleur te stellen en dingen om niet te vergeten. Hij had zich verdwaald gewaand in een stadsdeel uit de jaren tachtig tot er ineens uit het niks een onooglijke taxi van de elektrische variant was opgedoemd, waar hij zich nog net niet op had geworpen. De meter stond vooralsnog op zevenentwintig euro en een slordige vijfendertig centen. Op dit moment was het olijke tweetal, bestaande uit hemzelf en de taxichauffeur met psoriasis, nog steeds onderweg om zijn laptop op te halen bij zijn atelier. De honger vrat hem van binnenuit op en de kater vervloekte hem voor het tot tweemaal toe afslaan van een gebakken ei. In zijn portemonnee woonde helaas nog maar één briefje van vijftig euro, en daarbij had de chauffeur met het huidprobleem eerder nogal nors en negatief gegromd bij de notie dat hij niet direct naar de bestemming van zijn afspraak bliefde te gaan, maar dit via een stopplek op de locatie van zijn creativiteitsbunker wenste te doen.

De meter stond inmiddels op een bescheiden zesenveertig euro met een verwaarloosbaar aantal centen achter de komma. Het ritje had zich ontwikkeld tot een expeditie de treurnis in, zo leek het. Niet alleen wilde hij gillend alle haren uit zijn hoofd trekken en zijn ogen eruit krabben vanwege de stress en de vijfenveertig minuten die hij inmiddels te laat was; maar ook maakte het urbane landschap een dusdanig deprimerende indruk op hem dat hij zijn ziel in brand wenste te steken met wasbenzine, zodat het vuur hem van binnenuit zou kunnen verteren. De plaats van afspreken was op een dreef dan wel een kade, waar zowel hij als zijn roodgevlekte mobiele metgezel nog nooit van gehoord had. Van tijd tot tijd draaide de chauffeur zich om en wees naar wat façades die opgetrokken waren in een ‘leuke’ niet-leuke klassieke stijl. Vaak stelde de chauffeur hier ook nog een vraag bij, die hij dan niet goed kon verstaan.”

Pepijn Lanen (Utrecht, 4 augustus 1982)

De Engelse komiek, schrijver, acteur en presentator Stephen John Fry werd geboren in Londen op 24 augustus 1957. Zie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor Stephen Fry op dit blog.

Uit: The Liar

“Yes,” said Adrian. “You still haven’t told me who killed Moltaj.” “The Hungarians have a wonderful word,” said Trefusis. “It is puszipajtds and means roughly ‘someone you know well enough to kiss in the street.’ They are a demonstrative and affectionate people, the Hungarians, and enthusiastic social kissers. ‘Do you know young Adrian?’ you might ask and they might reply, ‘I know him, but we’re not exactly puszipajtas.'” “I have no doubt whatever in my mind,” said Adrian, “that all this is leading somewhere.” “A few weeks ago Bela’s grandson arrived in England. He is a chess player of some renown, having achieved grandmaster status at last year’s Olympiad in Buenos Aires. No doubt you followed his excellent match against Bent Larsen?” “No,” said Adrian. “I missed his match against Bent Larsen and somehow his matches against Queer Karpov and Faggoty Smyslov and Poofy Petrosian also managed to pass me by.” “Tish and hiccups. Bent is a perfectly common Danish Christian name and it would do you no harm, Master Healey, to acquire a little more patience.” “I’m sorry, Donald, but you do talk around a subject so.”

“Would you have said that?” Trefusis sounded surprised. “I would.” “I will then straight to the heart of the matter hie me. Stefan, the grandson of Bela, came to England a fortnight ago to play in the tournament at Hastings. I received a message to meet him in a park at Cambridge. Parker’s Piece to be exact. It was ten o’clock of a fine June night. That is not extraneous colour, I mention the evening to give you the idea that it was light, you understand?” Adrian nodded. “I walked to the rendezvous point. I saw Stefan by an elm tree clutching a briefcase and looking anxious. My specifying that the tree was an elm,” said Trefusis, “is of no consequence and was added, like this explanation of it, simply to vex you. The mention of the lad’s anxiety, however, has a bearing. The existence of the briefcase is likewise germane.” “Right.” “As I approached, he pointed to a small shed or hut-like building behind him and disappeared into it. I followed him.” “Ah! Don’t tell me . . . the small shed or hut-like building was in fact a gentlemen’s lavatory?”

Stephen Fry (Londen, 24 augustus 1957)

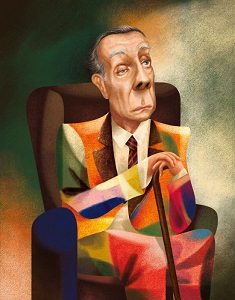

De Argentijnse schrijver Jorge Luis Borges werd geboren op 24 augustus 1899 in Buenos Aires. Zie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor Jorge Luis Borges op dit blog.

Uit:The Aleph (Vertaald door Andrew Hurley)

“At the end of one corridor, a not unforeseen wall blocked my path— and a distant light fell upon me. I raised my dazzled eyes; above, vertiginously high above, I saw a circle of sky so blue it was almost purple. The metal treads of a stairway led up the wall. Weariness made my muscles slack, but I climbed the stairs, only pausing from time to time to sob clumsily with joy. Little by little I began to discern friezes and the capitals of columns, triangular pediments and vaults, confused glories carved in granite and marble. Thus it was that I was led to ascend from the blind realm of black and intertwining labyrinths into the brilliant City. At the end of one corridor, a not unforeseen wall blocked my path— and a distant light fell upon me. I raised my dazzled eyes; above, vertiginously high above, I saw a circle of sky so blue it was almost purple. The metal treads of a stairway led up the wall. Weariness made my muscles slack, but I climbed the stairs, only pausing from time to time to sob clumsily with joy. Little by little I began to discern friezes and the capitals of columns, triangular pediments and vaults, confused glories carved in granite and marble. Thus it was that I was led to ascend from the blind realm of black and intertwining labyrinths into the brilliant City. I emerged into a kind of small plaza—a courtyard might better describe it. It was surrounded by a single building, of irregular angles and varying heights. It was to this heterogeneous building that the many cupolas and columns belonged. More than any other feature of that incredible monument, I was arrested by the great antiquity of its construction. I felt that it had existed before humankind, before the world itself. Its patent antiquity (though somehow terrible to the eyes) seemed to accord with the labor of immortal artificers. Cautiously at first, with indifference as time went on, desperately toward the end, I wandered the staircases and inlaid floors of that labyrinthine palace. (I discovered afterward that the width and height of the treads on the staircases were not constant; it was this that explained the extraordinary weariness I felt.) This palace is the work of the gods, was my first thought. I explored the uninhabited spaces, and I corrected myself: The gods that built this place have died. Then I reflected upon its peculiarities, and told myself: The gods that built this place were mad. I said this, I know, n a tone of incomprehensible reproof that verged upon remorse—with more intellectual horror than sensory fear. The impression of great antiquity was joined by others: the impression of endlessness, the sensation of oppressiveness and horror, the sensation of complex irrationality. I had made my way through a dark maze, but it was the bright City of the Immortals that terrified and repelled me. A maze is a house built purposely to confuse men; its architecture, prodigal in symmetries, is made to serve that purpose. In the palace that I imperfectly explored, the architecture had no purpose. There were corridors that led nowhere, unreachably high windows, grandly dramatic doors that opened onto monklike cells or empty shafts, incredible upside-down staircases with upside-down treads and balustrades. Other staircases, clinging airily to the side of a monumental wall, petered out after two or three landings, in the high gloom of the cupolas, arriving nowhere.”

Jorge Luis Borges (24 augustus 1899 – 14 juni 1986)

Portret door Goncalo Viana

De Engelse schrijfster A. S. Byatt werd geboren als Antonia Susan Drabble op 24 augustus 1936 in Sheffield. Zie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor A. S. Byatt op dit blog.

Uit: The Biographer’s Tale

“I made my decision, abruptly, in the middle of one of Gareth Butcher’s famous theoretical seminars. He was quoting Empedocles, in his plangent, airy voice. “Here sprang up many faces without necks, arms wandered without shoulders, unattached, and eyes strayed alone, in need of foreheads.” He frequently quoted Empedocles, usually this passage. We were discussing, not for the first time, Lacan’s theory of morcellement, the dismemberment of the imagined body. There were twelve postgraduates, including myself, and Professor Ormerod Goode. It was a sunny day and the windows were very dirty. I was looking at the windows, and I thought, I’m not going to go on with this anymore. Just like that. It was May 8th 1994. I know that, because my mother had been buried the week before, and I’d missed the seminar on Frankenstein.

I don’t think my mother’s death had anything to do with my decision, though as I set it down, I see it might be construed that way. It’s odd that I can’t remember what text we were supposed to be studying on that last day. We’d been doing a lot of not-too-long texts written by women. And also quite a lot of Freud-we’d deconstructed the Wolf Man, and Dora. The fact that I can’t remember, though a little humiliating, is symptomatic of the “reasons” for my abrupt decision. All the seminars, in fact, had a fatal family likeness. They were repetitive in the extreme. We found the same clefts and crevices, transgressions and disintegrations, lures and deceptions beneath, no matter what surface we were scrying. I thought, next we will go on to the phantasmagoria of Bosch, and, in his incantatory way, Butcher obliged. I went on looking at the filthy window above his head, and I thought, I must have things. I know a dirty window is an ancient, well-worn trope for intellectual dissatisfaction and scholarly blindness. The thing is, that the thing was also there. A real, very dirty window, shutting out the sun. A thing.

I was sitting next to Ormerod Goode. Ormerod Goode and Gareth Butcher were joint Heads of Department that year, and Goode, for reasons never made explicit, made it his business to be present at Butcher’s seminars. This attention was not reciprocated, possibly because Goode was an Anglo-Saxon and Ancient Norse expert, specialising in place-names. »

A. S. Byatt (Sheffield, 24 augustus 1936)

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Sascha Anderson werd geboren op 24 augustus 1953 in WeimarZie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor Sascha Anderson op dit blog.

eNDe IV

östwestlicher die wahn

machs gut mit spekulatius

machs gut mit kohlenanzünder dem weissen

machs gut mit erika love again

machs gut schöne grosse blonde leere

rin machs gut ödipus

machs gut unten spiegelverkehrt

eine nuance zu concafé machs gut

augenblicklich signiert machs gut ein

tv zwei

die macht sie fördert frauenliteratur unter dem aspekt

steigt laicht das bewusstsein ein frontstaat zu sein

machs gut im aquarium

sitzen immer die anderen machs gut

amnestie für die angebrochene

packung kekse marke favorit

Sascha Anderson (Weimar, 24 augustus 1953)

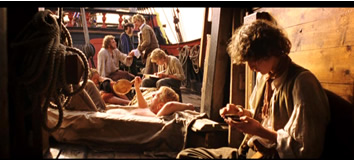

De Nederlandse schrijver Johan Johannes Fabricius werd op 24 augustus 1899 in Bandoeng in Nederlands-Indië geboren. Zie ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2010 en eveneens alle tags voor Johan Fabricius op dit blog.

Uit: De scheepsjongens van Bontekoe

“Peter Hajo bleef rustig. ‘Van wie is die emmer?’ vroeg hij.

‘Van mij,’ zei Padde. ‘En dit ene net is ook van mij.’

‘Top. Leg de rest neer. Een bijl hebben we niet nodig, want ik heb er nog een bijt.’

Padde ontdeed zich van twee netten die hem nog over de schouder hingen en gaf de bijl aan Lange Leen.

‘Laat ze maar lopen, jongens!’ zei deze.

‘Wedden, dat er in de hele Karperkuil geen onnozel botje zwemt?’ vroeg Padde, terwijl hij met Hajo meeliep.

‘Wacht even!’ riepen toen Schouwen Doedes en nog een paar jongens. ‘Wij gaan ook mee!’

‘Als je ’t maar laat,’ dreigde Hajo. ‘Nou heb ik jullie niet meer nodig.’

Hajo en Padde liepen de Korenmarkt over en daarna de Veermanskade langs met de hoge pakhuizen en deftige patriciërswoningen. Juist wilden ze bij de Hoofdtoren rechts afslaan, de Italiaanse zeedijk op, toen een Friese tjalk de haven kwam binnenzeilen. Haastig liepen ze toe om hem te helpen vastleggen. Het scheelde maar een haartje of Padde werd door het touw in het water getrokken, wat hij nog slechts kon voorkomen door aan boord te springen, waar hij voor de voeten van een gezelschap deftige heren terechtkwam. Verlegen krabbelde hij overeind.

De heren lachten en gingen aan wal. Hajo groette hen vol ontzag.

‘Wie waren dat?’ vroeg hij aan schipper Blok, de eigenaar van de tjalk.

‘Wel,’ zei Blok, ‘die met die baard, da’s schipper Bontekoe.’

‘Natuurlijk. Maar de anderen?’

‘Die bennen alle vijf van de Oostindische Compagnie. Die magere is uit Enkhuizen, en die dikke met z’n wijde handschoenen komt uit Zeeland. Ik heb ze met de Hoornse Zon?,’ Blok wees op z’n tjalk, ‘naar Texel moeten brengen en weer halen ook. Daar leidt de Nieuw-Hoorn, weet je?’

‘De Nieuw-Hoorn?’

‘De schuit van schipper Bontekoe, die naar Oostinje gaat. Je zou ‘m es moeten zien. Tweehonderd koppen aan boord!’

Hajo keek peinzend de deftig geklede heren na, die juist een ogenblik stilstonden voor Bontekoes woonhuis op de Veermanskade. ‘Zeg, Blok,’ vroeg hij, ‘wijs me eens hoe groot de Nieuw-Hoorn is.’

Johan Fabricius (24 augustus 1899 – 21 juni 1981)

Scene uit de gelijknamige film uit 2007

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 24e augustus ook mijn blog van 24 augustus 2014 deel 2.