De Franse dichter en schrijver Max Jacob werd op 12 juli 1876 geboren in Quimper. Zie ook alle tags voor Max Jacob op dit blog.

Poème

Quand le bateau fut arrivé aux îles de l’Océan Indien, on s’aperçut qu’on n’avait pas de cartes. Il fallut descendre. Ce fut alors qu’on connut qui était à bord: il y avait cet homme sanguinaire qui donne du tabac à sa femme et le lui reprend. Les îles étaient semées partout. En haut de la falaise, on aperçut à de petits nègres avec des chapeaux melon: “Ils auront peut-être des cartes.” Nous prîmes le chemin de la falaise: c’était une échelle de corde; le long de l’échelle, il y avait peut-être des cartes! des cartes même japonaises! Nous montions toujours. Enfin, quand il n’y eut plus d’échelons (des cancres en ivoire quelque part), il fallut monter avec les poignets. Mon frère l’Africain s’en acquitta très bien, quant à moi, je découvris des échelons où il n’y en avait pas. Arrivés en haut, nous sommes sur un mur; mon frère saute. Moi, je suis à la fenêtre! Jamais je ne pourrai me décider à sauter: c’est un mur de planches rouges. “Fais le tour”, me crie mon frère l’Africain. Il n’y a plus ni étages, ni passagers, ni bateau, ni petit nègre: il y a le tour qu’il faut faire. Quel tour! c’est décourageant.

Die Bettlerin von Neapel

Als ich in Neapel lebte, stand an der Tür meines Palastes eine Bettlerin, der ich stets vor dem Einsteigen in den Wagen Kleingeld zuwarf. Erstaunt, weil nie ein Dank kam, schaute ich die Bettlerin eines Tages an. Als ich sie so betrachtete, sah ich, daß das, was ich für eine Bettlerin gehalten hatte, ein grün angestrichener Holzkasten war, der rote Erde und einige halb verfaulte Bananen enthielt.

Vertaald door Johannes Beilharz

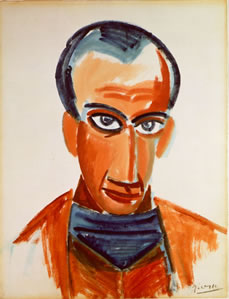

Portret door Picasso, 1907

De Amerikaanse dichter, schrijver en filosoof Henry David Thoreau werd geboren in Concord, Massachusetts op 12 juli 1817. Zie ook alle tags voor Henry David Thoreau op dit blog.

Pray to What Earth

Pray to what earth does this sweet cold belong,

Which asks no duties and no conscience?

The moon goes up by leaps, her cheerful path

In some far summer stratum of the sky,

While stars with their cold shine bedot her way.

The fields gleam mildly back upon the sky,

And far and near upon the leafless shrubs

The snow dust still emits a silver light.

Under the hedge, where drift banks are their screen,

The titmice now pursue their downy dreams,

As often in the sweltering summer nights

The bee doth drop asleep in the flower cup,

When evening overtakes him with his load.

By the brooksides, in the still, genial night,

The more adventurous wanderer may hear

The crystals shoot and form, and winter slow

Increase his rule by gentlest summer means.

On Fields O’er Which the Reaper’s Hand has Passed

On fields o’er which the reaper’s hand has pass’d

Lit by the harvest moon and autumn sun,

My thoughts like stubble floating in the wind

And of such fineness as October airs,

There after harvest could I glean my life

A richer harvest reaping without toil,

And weaving gorgeous fancies at my will

In subtler webs than finest summer haze.

Standbeeld in Walden Pond State Reservation

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Hermann Conradi werd op 12 juli 1862 in Jeßnitz geboren. Zie ook alle tags voor Hermann Conradi op dit blog.

Was frag’ ich nach Zeit und Stunde

Was frag’ ich nach Zeit und Stunde,

Wenn an deiner Brust ich lieg’ –

Wenn ich küsse von deinem Munde

Der Liebe süßseligen Sieg!

Wenn ich küsse die weißen Brüste,

Den knospenden, schwellenden Leib –

Was frag’ ich nach Zeit und Stunde,

Bei solch holdem Zeitvertreib! …

Was frag’ ich nach Zeit und Stunde,

Rast’ ich auf Linnen, schneeweiß,

Bei dir und trink’ dir vom Munde

Der Liebe süßseligen Preis!

Da füllt mich ein großes Genügen,

Mein wildes Begehren versinkt …

Was frag’ ich nach Zeit und Stunde,

Wenn die Welt wie verschollen mich dünkt! …

De Nederlands-Amerikaanse journalist en schrijver Hans Koning (pseudoniem van Hans Köningsberger) werd geboren in Amsterdam op 12 juli 1921. Zie ook alle tags voor Hans Koning op dit blog.

Uit: I Know What I’m Doing

„I was born in a dark, large house in Guildford, which is thirty miles southwest of London. My father died when I was six years old, and my stepfather hated me, or so I have thought since my earliest memories. When I was sixteen, he arranged a job for me with an insurance company in London; he had told my mother and me that I was not the type of girl for a college education. The work meant getting up at six, six days a week, a freezing cold bathroom (both summer and winter, it seemed), and a slow train into town with compartments smelling like my stepfather’s study where there was always a wet cigar butt in the ash tray.

It is strange for me to realize how little I remember of that time. When I think about it, I always see the same picture, of our dank and green garden which climbed a hillside, and of myself sitting on a bench near the upper road, reading; I read three or four books a week. When I was seventeen, my mother and stepfather went to the United States—he could not bear the Labour Party any longer, he informed my mother. He and I hardly exchanged a word in those days. My mother wasn’t bothered by the idea of leaving me alone in England, and they hardly suggested I come with them. I moved to a rooming house in London, a dreary but respectable place, and made some new friends, girls whose dates were boys at the universities; and I didn’t fit in too badly.

There was an autumn evening, about a year later. It was drizzling miserably as I came back from a dance. I stood in the doorway with the boy who had taken me there, and I had the sudden feeling that I could not go on with this kind of life one more day. I said good night and hastily went upstairs. A tepid smell came toward me as I opened the door: I had left my hot plate on. There was a knock; the man living on the floor above me said he had come to make sure the place wasn’t on fire. I told him it was all right, but as he hesitated, I offered to make tea. His entrance had stopped me from crying, which I had been set on doing, and I felt grateful toward him for that. He had recently come out of the army and was now studying to be an architect. I had gone to the movies with him once, but we hadn’t exchanged more than a dozen words. When he had asked me out again, I had said I was busy.“

De Nederlandese (Friese) schrijver Gerben Willem Abma werd op 12 juli 1942 geboren in Folsgare. Zie ook alle tags voor Willem Abma op dit blog.

Uit: De straf van Abe (Over „Gewassen vlees“ van Thomas Rosenboom)

„Hoe verliepen oproer en vonnissen volgens de historicus – dus niet volgens de rijke fantasie van de literaire schrijver – in Koudum en omstreken? Herfst 1992 is een werk over de historie van de streek waarin het boek voornamelijk speelt, rond Koudum dus, verschenen. Hierin komen ook de woelingen van 1748 en de reactie van de overheid aan de orde.

Volgens een proces voor het Hof van Friesland van 13 maart 1749 had Robijn Saskers van Koudum met anderen verscheidene malen de klok onwettig geluid en een gevangene ontzet. Maar hij zou tot zijn daden gedwongen zijn en werd derhalve onmiddellijk vrijgesproken: ab instantia geabsolveerd. Andries Andrieszn kreeg als leider van de juist genoemde acties de straf dat hem op het schavot ‘het zwaard over het hoofd’ gestreken werd, tien jaar tuchthuis en voor eeuwig verbanning uit de provincie. Met Sybren Saskers liep het nog erger af. Hij had ‘mede als hoofd-aanvoerder eener oproerige bende een gevangenen ontzet uit zijne detentie waartoe menschen zelvs door dwang uit hunne huizen waren mede genomen’. Op 18 april 1750 werd hij tot mijn niet geringe verrassing veroordeeld tot brandmerking, geseling, tien jaar tuchthuis en eeuwige verbanning uit de provincie.

Letterlijk de door Thomas Rosenboom vermelde straffen dus. Maar nu met vermelding van de bedreven daden.“