De Franse schrijver en journalist Patrick Besson werd geboren op 1 juni 1956 in Montreuil. Zie ook mijn blog van 1 juni 2009 en alle tags voor Patrick Besson op dit blog.

Uit:La mémoire de Clara

„La lumière d’automne l’a toujours rendue, rendue, rendue quoi? Elle ne sait plus. Elle regarde la rue Alphonse Karr. Il y a de l’eau qui tombe du ciel comme hier. Comment s’appelle l’eau qui tombe du ciel ? Elle sait : la pluie. Elle sourit. Il y a des choses qui lui reviennent de temps en temps, ça fait plaisir. C’est comme pour l’ascenseur. Une fois sur deux, elle sonne chez un copropriétaire, croyant appeler l’ascenseur. L’autre ouvre la porte. Un homme petit et chauve. Il sourit. À moins qu’il ne soupire. C’est un peu les deux. Il la ramène doucement devant la cabine d’ascenseur. Elle s’excuse : « Ah oui, pardon. » Il dit : « De rien, Mademoiselle Bruti. » Il lui donne son nom de jeune fille, celui sous lequel elle était connue et restera dans les livres d’Histoire de la cinquième République française. Personne ne l’a jamais appelée Madame Brancusi, sauf elle-même quand elle se regardait, il y a cinquante-trois ans, dans les miroirs de l’Élysée, ancienne demeure des présidents français avant que le Palais ne soit préempté par l’émir du Qatar et ne devienne le musée national du football français, le bureau du général De Gaulle et de Georges Pompidou étant consacré aux coupes gagnées par le PSG avant son rachat par l’émirat en 2011. Mais il y a aussi des jours, de moins en moins nombreux il est vrai, où Clara, pour l’ascenseur de la rue Alphonse Karr, ne se trompe pas. Les deux portes s’ouvrent comme la caverne d’Ali Baba. Elle est aussi heureuse que si elle recevait, une nouvelle fois, une Victoire de la musique. Quant à la lumière d’automne, elle se souvient maintenant de ce que ça la rendait : heureuse. C’est le soleil qui l’attriste. Pourquoi, alors, s’est-elle installée dans cette ville du sud dont le nom va lui revenir ? Pas Cannes, car elle n’a vu personne qu’elle connaît monter des marches. Mais connaît-elle encore les gens qu’elle connaît ? C’est un mot anglais. Une glace. Ice. Avec une lettre devant, mais quelle lettre ? Il faudrait qu’elle se concentre mais elle préfère regarder la, la, elle le savait tout à l’heure : la pluie, voilà.

Nice. Elle est à Nice. Elle est contente, elle s’est souvenue de deux choses : Nice et … Zut, elle a oublié la première. Il faut qu’elle écrive ses mémoires avant de perdre ses souvenirs. Non: ses souvenirs avant de perdre la mémoire. Elle doit appeler Aurélia, elles sont amies depuis si longtemps. Clara lui a piqué plusieurs mecs, ça crée des liens entre filles. »

Patrick Besson (Montreuil, 1 juni 1956)

De Engelse dichter en schrijver John Edward Masefield werd geboren op 1 juni 1878 in Ledbury, in Herefordshire. Zie ook mijn blog van 1 juni 2009 en eveneens alle tags voor John Masefield op dit blog.

Evening – Regatta Day

Your nose is a red jelly, your mouth’s a toothless wreck,

And I’m atop of you, banging your head upon the dirty deck;

And both your eyes are bunged and blind like those of a mewling pup,

For you’re the juggins who caught the crab and lost the ship the Cup

He caught a crab in the spurt home, this blushing cherub did,

And the Craigie’s Whaler slipped ahead like a cart-wheel on the skid,

And beat us fair by a boat’s nose though we sweated fit to start her,

So we are playing at Nero now, and he’s the Christian martyr.

And Stroke is lashing a bunch of keys to the buckle-end a belt,

And we’re going to lay you over a chest and baste you till you melt.

The Craigie boys are beating the bell and cheering down the tier,

D’ye hear, you Port Mahone baboon, I ask you, do you hear?

The Golden City of St. Mary

Out beyond the sunset, could I but find the way,

Is a sleepy blue laguna which widens to a bay,

And there’s the Blessed City — so the sailors say —

The Golden City of St. Mary.

It’s built of fair marble — white — without a stain,

And in the cool twilight when the sea-winds wane

The bells chime faintly, like a soft, warm rain,

In the Golden City of St. Mary.

Among the green palm-trees where the fire-flies shine,

Are the white tavern tables where the gallants dine,

Singing slow Spanish songs like old mulled wine,

In the Golden City of St. Mary.

Oh I’ll be shipping sunset-wards and westward-ho

Through the green toppling combers a-shattering into snow,

Till I come to quiet moorings and a watch below,

In the Golden City of St. Mary.

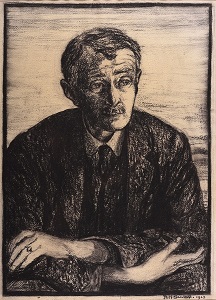

John Edward Masefield (1 juni 1878 – 12 mei 1967)

Portret door Rudolph Sauter, 1923

De Oostenrijkse schrijver Ferdinand Raimund werd geboren op 1 juni 1790 in Wenen. Zie ook mijn blog van 1 juni 2009 en eveneens alle tags voor Ferdinand Raimund op dit blog.

Uit: Die unheilbringende Krone

Phalarius (tritt mit wild zurückschauenden Blicken hastig ein, er trägt ein Pantherfell über dem Rücken und ist mit Bogen und Pfeil bewaffnet).

Bin ich denn noch nicht weit genug gezogen,

Verräterische Stadt, die mich betrogen?

Wird auch des Waldes düstre Einsamkeit

Durch deines Jubels frechen Schall entweiht?

(Die letzten Worte des Jubelchores erklingen wieder:

»Herrsch’ Kreon in Agrigent.«

Herrsch’ nur Kreon, Volk, jauchz’ die Kehle wund,

Ihr zwingt das Glück zu keinem ew’gen Bund.

Prahlt, Lügner, mit der Kron’, die ich erkämpft,

Da nur mein Mut des Krieges Glut gedämpft.

Mich laßt aus Undank meinen Purpur weben,

Ihn färben mit dem ausgeströmten Leben.

Das ich vergeudet am ersiegten Strand,

Den Lorbeer brechend mit der blut’gen Hand.

Glaubt ihr, ich hab’ für Agrigent gestritten,

Damit der Rat, nach ungerechten Sitten,

Das Reich verkauft an den unmünd’gen Knaben,

Auf das nur ich ein wahrhaft Recht kann haben?

Denn ist er auch dem Thron verwandt durch Blut,

Bin ich es würd’ger noch durch Heldenmut.

Ich glaub’ nicht, was des Tempels Diener sagten,

Als schlau sie Jupiters Orakel fragten,

Ob mir, ob wohl Kreon das Reich gehört;

Es hab’ der Gott sich donnernd drob’ empört,

Daß ich’s gewagt, als meiner Siege Lohn,

Zu fordern Agrigentens goldnen Thron,

Und ausgesprochen unter ew’gen Blitzen;

»Ich dürfe nie ein Reich der Welt besitzen,

Und Agrigent kann dann nur Glück erringen,

Wird auf dem Thron Kreon das Zepter schwingen.«

So logen sie, als ich zurückgekehrt,

Aus blut’ger Schlacht zum heißerkämpften Herd,

So logen sie, von aller Scham entwöhnt,

Als Siegesdank fand ich Kreon gekrönt.

Da außen ich des Landes Feind bekriegt,

Hat eigner mich im Innern hier besiegt.

Drum will ich fliehn aus dir, verhaßtes Land,

Doch nimm den Schwur als dräuend Unterpfand,

Daß ich noch einmal zu dir wiederkehre,

Zu rächen die durch Trug geraubte Ehre.

Ferdinand Raimund (1 juni 1790 – 5 september 1836)

Affiche voor een opvoering in Gutenstein, 2007

De Duitse schrijver, essayist, journalist, biograaf en uitgever Peter de Mendelssohn werd op 1 juni 1908 in München geboren. Zie ook mijn blog van 1 juni 2009 en eveneens alle tags voor Peter de Mendelssohn op dit blog.

Uit: Das zweite Leben

„Die Sozialdemokraten würden ebensowenig zu sagen haben, auch von ihnen saß die Hälfte schon im Gefängnis, die andere Hälfte würde den Mund nicht aufmachen, wenn es darauf ankäme. Wer würde seinen Mund aufmachen? Wer würde auftreten gegen die Tyrannei der Mörder, Diebe, Lügner und Betrüger? Wer würde seine Stimme gegen diese falschen Propheten erheben? Wer anders konnte in dieser Stunde noch helfen, als Gott?

Gott – – ich wußte wenig oder gar nichts von Gott. Ich kannte ihn kaum. war ich je in Seinem Hause gewesen? Ich war Protestant, wenn mich diese Welt auch zum Juden stempeln wollte. Ja, ich war protestantisch, auch meine Frau und mein Kind waren es. Aber in der Tiefe meines Herzens, so dachte ich während der wenigen, kostbaren Augenblicke in dieser würfelförmigen Zelle, bin ich ebensowenig Protestant wie Jude. Nein, ich kannte es nicht, das Antlitz des Judengottes, ich kannte Ihn nicht, ebensowenig aber kannte ich den Gott Martin Luthers. Trotzdem kannte ich Gott. Einmal hatte ich Ihn sogar recht gekannt, damals, als ich am sinkenden Abend durch die Felder ging, als Friede und Ruhe über meinen Tal lagen und auch mein Herz voll Frieden und Ruhe war. Da hatte ich Ihn kennengerlernt. Ich hatte Ihn nicht vergessen.

Als ich nun mein kleines Kreuz in den Kreis malte, der der katholischen Kirche zugehörte, da schämte ich mich sehr. Rasch faltete ich den Zettel zusammen und steckte ihn in den blauen Umschlag. Ich wußte nicht einmal, wie die Leute hießen, denen ich meine Stimme gegeben hatte. Aber auf jeden Fall glaubten sie an Gott. Wahrscheinlich würden sie in den kommenden Tagen wenig zu sagen haben, vielleicht gar nichts. Das würde ihnen aber wenig ausmachen. Sie würden weiter an Gott glauben.“

Peter de Mendelssohn (1 juni 1908 – 10 augustus 1982)

Gezicht op de Marienplatz in München door Charles Vetter, 1912

De Australische schrijfster Colleen McCullough werd geboren op 1 juni 1937 in Wellington. Zie ook mijn blog van 1 juni 2009 en eveneens alle tags voor Colleen McCullough op dit blog.

Uit: The Thorn Birds

“You bloody little bastards!”

Jack and Hughie scrambled to their feet and ran, the doll forgotten; when Frank swore it was politic to run.

“If I catch you flaming little twerps touching that doll again I’ll brand your shitty little arses!” Frank yelled after them.

He bent down and took Meggie’s shoulders between his hands, shaking her gently.

“Here, here there’s no need to cry! Come on now, they’ve gone and they’ll never touch your dolly again, I promise. Give me a smile for your birthday, eh?”

Her face was swollen, her eyes running; she stared at Frank out of grey eyes so large and full of tragedy that he felt his throat tighten. Pulling a dirty rag from his breeches pocket, he rubbed it clumsily over her face, then pinched her nose between its folds.

“Blow!”

She did as she was told, hiccuping noisily as her tears dried. “Oh, Fruh-Fruh-Frank, they too-too-took Agnes away from me!” She sniffled. “Her huh-huh-hair all falled down and she loh-loh-lost all the pretty widdle puh-puh-pearls in it! They all falled in the gruh-gruh-grass and I can’t find them!”

The tears welled up again, splashing on Frank’s hand; he stared at his wet skin for a moment, then licked the drops off.

“Well, we’ll have to find them, won’t we? But you can’t find anything while you’re crying, you know, and what’s all this baby talk? I haven’t heard you say ‘widdle’ instead of ‘little’ for six months! Here, blow your nose again and then pick up poor… Agnes? If you don’t put her clothes on, she’ll get sunburned.”

He made her sit on the edge of the path and gave her the doll gently, then he crawled about searching the grass until he gave a triumphant whoop and held up a pearl.

“There! First one! We’ll find them all, you wait and see.”

Meggie watched her oldest brother adoringly while he picked among the grass blades, holding up each pearl as he found it; then she remembered how delicate Agnes’s skin must be, how easily it must burn, and bent her attention on clothing the doll. There did not seem any real injury. Her hair was tangled and loose, her arms and legs dirty where the boys had pushed and pulled at them, but everything still worked. A tortoise-shell comb nestled above each of Meggie’s ears; she tugged at one until it came free, and began to comb Agnes’s hair, which was genuine human hair, skillfully knotted onto a base of glue and gauze, and bleached until it was the color of gilded straw.”

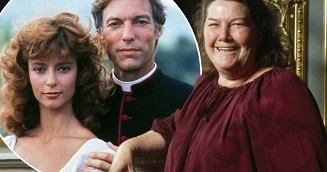

Colleen McCullough (1 juni 1937 – 29 januari 2015)

Hier met de hoofdrolspelers uit de tv-serie Richard Chamberlain en Rachel Ward

De Argentijnse schrijver Macedonio Fernández werd geboren op 1 juni 1874 in Buenos Aires. Zie ook mijn blog van 1 juni 2009 en alle tags voor Macedonio Fernández op dit blog.

Uit: From The Museum of Eterna’s Novel (Vertaald door Margaret Schwartz)

“So now I am obliged to deserve it, composing myself a past as an author in one fell swoop, so that later I’ll be able to write. This is a new situation in the life of writers, and isn’t it adverse to success?

You who have read me before I began to write, if you have a problem like mine, by now I don’t have it any more. I’ve finished my Complete Works. In my satisfaction, monumentally incapable of understanding difficulty, I can give you a distillation of long experience in art, collected in the present Complete Work.

Let art be limitless and free and all that is intrinsic to it—its handwriting, its titles, the life of its exponents. Tragedy or Humorism or Fantasy should never have to suffer a Past director, nor should they have to copy a Present Reality, and all should incessantly be judged, abolished.

It’s an axiomatic error to define art by copies: I understand life without getting a copy of it first; if copies were necessary, each new situation, each new character that we encountered would be eternally incomprehensible. The effectiveness of the author derives solely from his Invention.”

Macedonio Fernández (1 juni 1874 – 10 februari 1952)

Portret door Beti Alonso, 2010

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata:

Elena Ferrante (Napels, 1943) is het pseudoniem van een anonieme Italiaanse schrijfster die wordt beschouwd als een belangrijke vertegenwoordiger van de hedendaagse literatuur. Zij kwam voor het eerst in de jaren 1990 als romanschrijfster in de publiciteit en verkondigde in een interview de mening dat een roman na voltooiing roman geen nader auteurschap meer nodig heeft. Over de identiteit van de persoon achter het pseudoniem is steeds weer gespeculeerd in de media. Een tijd lang werd schrijfster Fabrizia Ramondino beschouwd als een waarschijnlijke kandidaat. Deze theorie werd weerlegd toen na haar dood meer romans van Elena Ferrante verschenen. Hoogleraar hedendaagse geschiedenis aan de Universiteit van Napels, Marcella Marmo, werd als auteur geïdentificeerd door de literatuurcriticus Marco Santagata, maar zij ontkende dit meerdere malen. Ferrante beschouwt het als een verkeerde ontwikkeling dat in het openbaar de identiteit van de auteur belangrijker is dan zijn werk. De journalist Claudio Gatti, trekt op grond van bankoverschrijvingen van de uitgever en van die toegang hebben tot de vergoeding hadden gekregen brengt de uitgever van Ferrante, trekt uit deze en uit kadastrale gegevens de conclusie dat het bij Ferrante moet gaan om Anita Raja die officieel voor dezelfde uitgever werkzaam is als vertaalster. Gatti publiceerde de resultaten van zijn onderzoek op 2 oktober 2016 tegelijkertijd in vier kranten, waaronder de Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung. De procedure van Gatti wordt bekritiseerd door sommige media als sensatie-journalistiek en als onrechtmatige inbreuk op de privacy van de auteur. Elena Ferrante debuteerde met “L’amore molesto” (1992), een roman die in 1995 werd verfilmd door Mario Martone. Het boek gaat over de jonge Delia, die druk is met de dood van haar moeder Amalia, die ofwel is verdronken ofwel werd vermoord. Tegelijk is deze preoccupatie met haar moeder een confrontatie met haar eigen verleden en haar afkomst van een uitgebreide familie uit Napels. In de roman “I giorni dell ‘abbandono” (2002) beschrijft ze het leven in Turijn van een echtpaar da”t gaat scheiden, en in het bijzonder hoe de vrouw deze scheiding verwerkt en haar eigen identiteit vindt. De roman werd in 2005 verfilmd door Roberto Faenza. De roman “La figlia oscura”verscheen in 2006, gevolgd in 2011 door “L’amica geniale”. De literaire criticus James Wood zorgde in januari 2013 met een lofrede in New York voor de doorbraak van Ferrante op de Amerikaanse boekenmarkt. In 2015 werd deze roman gekozen door de BBC selectie van de beste 20 romans uit de periode 2000-2014 als een van de belangrijkste werken tot nu toe in deze eeuw. Haar roman “Storia della bambina perduta” (Het verhaal van de verloren kind) werd genomineerd voor de Man Booker International Prize 2016 Ferrante publiceerde in 2003 onder de titel “La frantumaglia” een verzameling van reeds elders gepubliceerde interviews en een selectie uit de correspondentie met haar uitgever, aangevuld met een toelichting op haar werk. Het boek moest voldoen aan de vraag van het lezerspubliek naar meer informatie. In 2016 werd deze bundel gepubliceerd in een bijgewerkte versie.

Uit: The Story of the Lost Child (Vertaald door Ann Goldstein)

“From October 1976 until 1979, when I returned to Naples to live, I avoided resuming a steady relationship with Lila. But it wasn’t easy. She almost immediately tried to reenter my life by force, and I ignored her, tolerated her, endured her. Even if she acted as if there were nothing she wanted more than to be close to me at a difficult moment, I couldn’t forget the contempt with which she had treated me.

Today I think that if it had been only the insult that wounded me – You’re an idiot, she had shouted on the telephone when I told her about Nino, and she had never, ever spoken to me like that before – I would have soon calmed down. In reality, what mattered more than that offense was the mention of Dede and Elsa. Think of the harm you’re doing to your daughters, she had warned me, and at the moment I had paid no attention. But over time those words acquired greater weight, and I returned to them often. Lila had never displayed the slightest interest in Dede and Elsa; almost certainly she didn’t even remember their names. If, on the phone, I mentioned some intelligent remark they had made, she cut me off, changed the subject. And when she met them for the first time, at the house of Marcello Solara, she had confined herself to an absentminded glance and a few pat phrases – she hadn’t paid the least attention to how nicely they were dressed, how neatly their hair was combed, how well both were able to express themselves, although they were still small. And yet I had given birth to them, I had brought them up, they were part of me, who had been her friend forever: she should have taken this into account – I won’t say out of affection but at least out of politeness – for my maternal pride. Yet she hadn’t even attempted a little good-natured sarcasm; she had displayed indifference and nothing more. Only now – out of jealousy, surely, because I had taken Nino – did she remember the girls, and wanted to emphasize that I was a terrible mother, that although I was happy, I was causing them unhappiness. The minute I thought about it I became anxious. Had Lila worried about Gennaro when she left Stefano, when she abandoned the child to the neighbor because of her work in the factory, when she sent him to me as if to get him out of the way? Ah, I had my faults, but I was certainly more a mother than she was.”

Elena Ferrante (Napels, 1943)

Cover