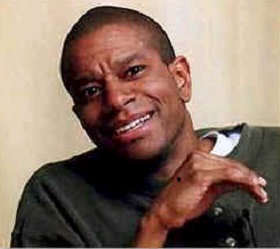

De Amerikaanse schrijver Paul Beatty werd geboren op 9 juni 1962 in Los Angeles. Beatty berhaalde een MFA in creatief schrijven aan Brooklyn College en een MA in psychologie aan de Universiteit van Boston. Daarvoor had hij, in 1980, eindexamen gedaan aan de El Camino Real High School in Woodland Hills, Californië. In 1990 werd Beatty gekroond tot de allereerste Grand Poetry Slam Champion of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. Tot de prijzen behoorde het uitgeven van zijn eerste dichtbundel “Big Bank Takes Little Bank” (1991). Deze werd gevolgd door een andere poëziebundel “Joker, Joker, Deuce” (1994), en optredens op MTV en PBS (in de serie The United States of Poetry). In 1993 ontving hij eeen beurs van de Foundation for Contemporary Arts Grants to Artists Award. Zijn eerste roman, “The White Boy Shuffle” (1996), kreeg een positieve recensie in The New York Times van Richard Bernstein. Zijn tweede boek, “Tuff” (2000), werd ook positief ontvangen. In 2006, bewerkte Beatty een bloemlezing van de Afro-Amerikaanse humor genoemd Hokum en schreef een artikel in The New York Times over hetzelfde onderwerp. Zijn roman uit 2008, “Slumberland”, ging over een Amerikaanse DJ in Berlijn. In zijn roman “The Sellout” uit 2015 verteltt Beatty over een stedelijke boer die een revitalisering nastreeft van slavernij en segregatie in een fictieve wijk in Los Angeles.

Uit: The Sellout

“I suppose that’s exactly the problem-I wasn’t raised to know any better. My father was (Carl Jung, rest his soul) a social scientist of some renown. As the founder and, to my knowledge, sole practitioner of the field of Liberation Psychology, he liked to walk around the house, aka “the Skinner box,” in a laboratory coat. Where I, his gangly, absentminded black lab rat was homeschooled in strict accordance with Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. I wasn’t fed; I was presented with lukewarm appetitive stimuli. I wasn’t punished, but broken of my unconditioned reflexes. I wasn’t loved, but brought up in an atmosphere of calculated intimacy and intense levels of commitment. We lived in Dickens, a ghetto community on the southern outskirts of Los Angeles, and as odd as it might sound, I grew up on a farm in the inner city. Founded in 1868, Dickens, like most California towns except for Irvine, which was established as a breeding ground for stupid, fat, ugly, white Republicans and the chihuahuas and East Asian refugees who love them, started out as an agrarian community. The city’s original charter stipulated that “Dickens shall remain free of Chinamen, Spanish of all shades, dialects, and hats, Frenchmen, redheads, city slickers, and unskilled Jews.” However, the founders, in their somewhat limited wisdom, also provided that the five hundred acres bordering the canal be forever zoned for something referred to as “residential agriculture,” and thus my neighborhood, a ten-square-block section of Dickens unofficially known as the Farms was born. You know when you’ve entered the Farms, because the city sidewalks, along with your rims, car stereo, nerve, and progressive voting record, will have vanished into air thick with the smell of cow manure and, if the wind is blowing the right direction-good weed. Grown men slowly pedal dirt bikes and fixies through streets clogged with gaggles and coveys of every type of farm bird from chickens to peacocks. They ride by with no hands, counting small stacks of bills, looking up just long enough to raise an inquisitive eyebrow and mouth: “Wassup? Q’vo?” Wagon wheels nailed to front-yard trees and fences lend the ranch-style houses a touch of pioneer authenticity that belies the fact that every window, entryway, and doggie door has more bars on it and padlocks than a prison commissary. Front porch senior citizens and eight-year-olds who’ve already seen it all sit on rickety lawn chairs whittling with switchblades, waiting for something to happen, as it always did.”

Paul Beatty (Los Angeles, 9 juni 1962)