De Iraanse schrijfster Shahrnush Parsipur werd geboren op 17 februari 1946 in Teheran. Zie ook alle tags voor Shahrnush Parsipur op dit blog.

Uit: Prison Memoir (Vertaald door Sara Khalili)

“It was nighttime, the prisoners were lying down on the floor, pressed against each other. But, to my surprise, they were all awake. Total silence reigned over the unit. It was a strange scene. Contrary to all other times, there was no line at the bathroom door. Instead, a few prisoners had gathered round the radiator and they were taking turns climbing on top of it so that they could look out from the window set high in the wall. One of them was Iran, and another, Farzaneh. Both were monarchists. The rest belonged to various other groups.

When I walked out of the bathroom, I saw Iran climb down from the radiator. She was shaking. Although we were not friends, she took me by the arm and whispered that the bodies of the executed prisoners had been laid out on one side of the courtyard. That night, starting at eleven o’clock, we had heard an earsplitting noise every few minutes. One of the prisoners had explained that they were building visitors’ rooms and that the noise was from the steel beams being dropped to the ground. Just then, we heard the noise again, and Iran, who was in shock, started to shake even more. I asked her, ‘What is this noise?’ she said. ‘Heavy machine gun fire.’ I didn’t know what a heavy machine gun was. I left the people who were again climbing up on the radiator and walked back to my room. I felt uneasy.

That day, at about two in the afternoon, I had seen two girls leave the unit. They were very beautiful. They were wearing shoes and to avoid dirtying the pieces of carpeting on the floor, they moved toward the door on their knees. I had asked their names and ages. They looked like twins, seventeen at most, but they explained that they were actually aunt and niece. The image of their amiable faces had stayed in my mind. I had not seen them return. Now I was looking more carefully at the prisoners. They were silent and staring directly ahead.

When I reached my room, Farideh, who managed the room across the hall, was standing in the doorway. I asked her, ‘What is going on?’ She said, ‘It’s heavy machine gun fire. Can’t you hear it?’ I asked, ‘What is heavy machine gun fire?’ She explained that when they carried out mass executions, they used heavy machine guns and this was the sound of the shower of bullets being fired. Then she said everyone was quiet so that they could hear the single shots; after each shower of bullets, a single shot was delivered to the head of each prisoner. The prisoners were counting the single shots. So far, they had counted more than ninety”.

Shahrnush Parsipur (Teheran, 17 februari 1946)

De Nederlandse dichter Willem Thies werd geboren op 17 februari 1973 in Nijmegen. Zie ook alle tags voor Willem Thies op dit blog.

Vel over vel

kortstondig de kinderen die spelevaren op de vijver

schoorvoetend gaat het volk voorbij

een monitor toont iets afwijkends

iemand zucht – kucht

twee vrouwen twijfelen over de aankoop

van een bundel

‘steek je hand onder een bladzijde en je schrikt

je ziet de poriën in je huid

zó dun is het papier’

Kerkhof

Het stormt in de schaduwrijke nacht

ik bezoek een joods kerkhof; sterren en stenen

dit is mijn droomachtige

dronken wat dan ook

werkelijkheid

en ik denk: te weinig plaats voor zoveel joden

ook al zijn ze dood

Tegendraads

Slapend schik ik mij naar het lichaam van mijn inmiddels geliefde.

Haar kin tussen mijn schouderbladen.

Overdag blijf ik tegendraads.

Kerf ik mijn voorhoofd tot wijdvertakte webben als zij iets vraagt.

Wellen mijn woorden op in haar ooghoeken.

Schuif ik de nacht van mij af als een slecht boek.

Ik scheid wat van de wijn is en wat van mij

schenk allengs minder van mijzelf in het glas.

Ik slink tot een woedende kring op het tafelblad.

Willem Thies (Nijmegen, 17 februari 1973)

De Iraanse schrijver Sadegh Hedayat werd geboren op 17 februari 1903 in Teheran. Zie ook alle tags voor Sadegh Hedayat op dit blog.

Uit: De blinde uil (Vertaald door Gert J.J. de Vries)

“Er bestaan bepaalde pijnen die als een traag, onzichtbaar woekerend kankergezwel de geest aanvreten.

Dergelijke pijnen laten zich aan niemand duidelijk maken. Mensen zijn het gewend om deze ongelooflijke kwellingen af te doen als bizarre gedachtespinsels. Hoezeer je je ook inspant om daar duidelijkheid over te geven, mondeling of schriftelijk, je krijgt altijd de geijkte reacties of juist een persoonlijke verklaring te horen. Dikwijls zullen je klachten ook een ironische of spottende glimlach ontlokken.

Het gaat hier immers om een kwaal waarvoor de mensheid nog geen behandeling of medicijn heeft ontwikkeld. Alleen de kunstmatige beneveling van alcohol, opium of soortgelijke roesmiddelen zou de pijn kunnen verlichten. Helaas werken dergelijke middelen slechts tijdelijk en zullen die de pijn na enige tijd eerder verscherpen dan verlichten.

Zal iemand er ooit in slagen de geheimen te doorgronden van deze onaardse dimensie; van dit schimmige, comateuze rijk, van dit grensgebied tussen dromen en waken?

Mijn verhaal beperkt zich tot de gebeurtenissen die ik persoonlijk heb ervaren en die mij zodanig hebben geschokt dat ze me altijd zullen bijblijven. De herinnering aan dit onheil zal de rest van mijn leven, tot mijn allerlaatste ademtocht, vergallen – met een intensiteit die elk menselijk begrip te boven gaat. ‘Vergallen,’ zei ik, maar eigenlijk bedoel ik dat ik het litteken ervan altijd gedragen heb en altijd zal blijven dragen. Ik zal een poging doen om mijn herinneringen op te schrijven; om dat op te schrijven waarvan ik meen dat het ter zake doet. Misschien slaag ik er dan in vat op de gebeurtenissen te krijgen. Of nee, om tenminste aan mijn twijfels een eind te maken en om mijn eigen herinneringen te kunnen geloven. Want of ik anderen al dan niet kan overtuigen, laat mij volstrekt onverschillig. Er is slechts één angst die me bezighoudt en dat is dat ik morgen zou sterven zonder mezelf te hebben gekend. In de loop van mijn leven heb ik gemerkt dat er een diepe kloof bestaat tussen mij en mijn medemensen.”

Sadegh Hedayat (17 februari 1903 – 9 april 1951)

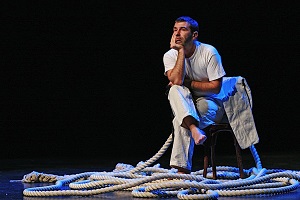

De Russische schrijver, regisseur en acteur Yevgeni Grishkovetz werd geboren op 17 februari 1969 in Kemerovo. Zie ook alle tags voor Yevgeni Grishkovetz op dit blog.

Uit: How I Ate the Dog

“The person who has just woken up: “Yeah?! Well, all the same, what beauty…!” Tuduk-tuk-tuk, tuduk-tuk-tuk…

Two sailors took us, they wore white dress uniforms and really looked after their appearance. Both were short, one had a moustache that he really loved and obviously was very proud of, you couldn’t make it out immediately, but if you so desired, it wasn’t hard to count all the tiny hairs he had on his upper lip, and the other was, I for some reason recall, from Tambov, he was bowlegged and right about here he wore a medal “For faraway deployment.” They got out at every station and walked around the platform with an old cassette player, glancing to the sides, meaning – Are they looking at us or not? Aha…they’re looking! Very good! I was surprised at the time by how their sailor hats stayed on the back of their heads, it was obvious that they should have fallen off, but they stayed on, all the same…. Without any sense of idiotic metaphor, they hung like haloes…. I only found out later, how they stayed on… sailor hats. And that there’s no secret, they simply stay on, and that’s it.

The sailors were entertaining…. We came up to them with questions about how it is, and they gladly told us how…: “Well, we went through La Pérouse Strait, then we went to Cam Ranh, we stopped there…, then we went to New Zealand and they didn’t let us come ashore, but in Australia they let us come ashore, but only the officers went and…”

And I was thinking: “Geeeeee whiz… After all I studied English in school… Why?” Well, there were countries where they speak this language, there was Europe, well somewhere there… Paris, London, you know, Amsterdam, there were those, and leave it at all that. What’s it to me? They sometimes vaguely disturbed you in that they nevertheless kind of existed…, but they didn’t draw out any concrete desire. The world was huge, like in a book….

And these sailors had been, my God, in Australia, New Zealand…. And the same awaits me, just put me in that same uniform…. And little by little, already quickly, the train takes us to Vladivostok, and there is still a little left – and some sort of sea, some sort of countries…. Reluctance!!!! Because even though I didn’t know anything concrete, I suspected that, well, of course, it wasn’t quite that simple, Australia, New Zealand, and still some other place like that, the essential of what I didn’t want to know, of what I was afraid, of what I was very afraid and what would very soon come up… without fail….”

Yevgeni Grishkovetz (Kemerovo, 17 februari 1969)

Cover

De Nederlandse schrijver Albert Kuyle werd geboren in Utrecht op 17 februari 1904. Zie ook alle tags voor Albert Kuyle op dit blog.

Uit: Harten en Brood

“Ergens in de wereld loopen schapen. Ze hebben genoeg ervan, op het plaatje te staan, waarop de zon achter hen onder gaat, en waarop de herder met zijn hond hen naar een schilderachtige schaapskooi drijft. ‘Keerende kudde’. ‘Naar huis’. ‘Als het avond wordt…’. Het zijn die wollige, sentimenteele mekkerdieren niet, die in massa optreden om de burger een lustschokje van ontroering te bezorgen. Het zijn ook de schapen niet, die alleen in verhalen en predikaties bestaan, de schapen met de ééne schaapstal, met de goede en de trouwelooze herder, met de wolf-in-een-vacht, de schapen van de arme herder, die niet tegen het rumoerige leven op kan.

Het zijn de schapen van het groote, daverende land. De schapen, die met duizenden geboren worden en met tienduizenden geschoren. De vrije, gedreven, optrekkende schapen, die van een paard af gehoed en met prikkeldraad bedwongen worden. Ze zijn het eigendom van harde gelooide kerels, die hun heele bezit op pooten hebben loopen en die aan de radio luisteren naar de dagprijs van de wol. Op een dag, een blauwe of een grijze, dat speelt geen rol, verliezen zij hun vacht. Hun vacht die vet, lang en zacht is, en die de vage geur van de thijm en de harde grassen heeft, die zij vraten. Zij worden gebonden, getrapt en geschoren en ze gaan kaal en onaanzienlijk de prairie weer in. Hun wol gaat verder, die dwaalt en dwaalt, in pakken en in balen, die wordt schoon en wit, en tenslotte tot een onherkenbare draad.

Dan is van Duin aan de beurt. Neen, niet van Duin, maar het werk dat hij bewaakt. Dat vangt de draden en de draden worden stukken goed. Roode en blauwe en grijze, en geruite en gestreepte met een graat als van gekookte snoek… Dan is het voorbij. Dan is het leven hem gepasseerd, en met de jassen, de mantels, de broeken en de doeken, die volgen, heeft hij al niets meer uit te staan. Die worden gedragen door menschen die hij niet kent en die hem er zeker niet dankbaar voor zijn dat hij de draad tot lappen maakte.

Van Duin is er een beetje trotsch op, dat dat heele verhaal in de loop van de jaren in hem aan elkaar is gaan zitten. Hij koestert het in zich, en hij zegt tegen de dokter en tegen zijn vrienden: ‘Ik ben ook een beetje filosoof, op mijn manier natuurlijk’.”

Albert Kuyle (17 februari 1904 – 4 maart 1958)

De Tsjechische dichter en schrijver Jaroslav Vrchlický (eig. Emilius Jakob Frida) werd geboren op 17 februari 1853 in Louny, Bohemen. Zie ook alle tags voor Jaroslav Vrchlický op dit blog.

Metempsychosis

Oftentimes as I sleep, my soul is musing

how down the ages, borne by change, wings beating,

I cruised the starry depths, in thought un-fleeting,

menhir, then wave, then tree, then bird, enthusing.

Via such diverse forms, each stepwise using,

in human-kind I woke, heart anxious beating,

a fledgling’s fall, from woman’s soul, world-meeting,

my soul both suffering and love effusing.

Before I simply lived. Now love’s pained feeling

gives me pause, to the top step I’ve been bidden,

all changes rung; my final goal reached nearly:

Might godliness now lift the mask, revealing

clearly what hence I’ve sensed, by smoke’s veil hidden,

or must I perish now, drawn void-ward merely.

Vertaald door Václav ZJ Pinkava

Jaroslav Vrchlický (17 februari 1853 – 9 september 1912)

Als student in 1874

De Amerikaanse schrijver Chaim Potok werd geboren in New York City op 17 februari 1929. Zie ook alle tags voor Chaim Potok op dit blog.

Uit: The Chosen

“Davey Cantor, one of the boys who acted as a replacement if a first-stringer had to leave the game, was standing near the wire screen behind home plate. He was a short boy, with a round face, dark hair, owlish glasses, and a very Semitic nose. He watched me fix my glasses.

“You’re looking good out there, Reuven,” he told me.

“Thanks,” I said.

“Everyone is looking real good.”

“It’ll be a good game.”

He stared at me through his glasses. “You think so?” he asked.

“Sure, why not?”

“You ever see them play, Reuven?”

“No.”

“They’re murderers.”

“Sure,” I said.

“No, really. They’re wild.”

“You saw them play?”

“Twice. They’re murderers.”

“Everyone plays to win, Davey.”

“They don’t only play to win. They play like it’s the first of the Ten Commandments.”

I laughed. “That yeshiva?” I said. “Oh, come on, Davey.”

Chaim Potok (17 februari 1929 – 23 juli 2002)

De Chinese schrijver Mo Yan werd geboren op 17 februari 1955 in Gaomi in de provincie Shandong. Zie ook alle tags voor Mo Yan op dit blog.

Uit: Red Sorghum (Vertaald door Howard Goldblatt)

“The autumn winds are cold and bleak, the sun’s rays intense. White clouds, full and round, float in the tile-blue sky, casting full round purple shadows onto the sorghum fields below. Over decades that seem but a moment in time, lines of scarlet figures shuttled among the sorghum stalks to weave a vast human tapestry. They killed, they looted, and they defended their country in a valiant, stirring ballet that makes us unfilial descendants who now occupy the land pale by comparison. Surrounded by progress, I feel a nagging sense of our species’ regression.

After leaving the village, the troops marched down a narrow dirt path, the tramping of their feet merging with the rustling of weeds. The heavy mist was strangely animated, kaleido-scopic. Tiny droplets of water pooled into large drops on Father’s face, clumps of hair stuck to his forehead. He was used to the delicate peppermint aroma and the slightly sweet yet pungent odour of ripe sorghum wafting over from the sides of the path — nothing new there. But as they marched through the heavy mist, his nose detected a new, sickly-sweet odour, neither yellow nor red, blending with the smells of peppermint and sorghum to call up memories hidden deep in his soul.

Six days later, the fifteenth day of the eighth month, the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival. A bright round moon climbed slowly in the sky above the solemn, silent sorghum fields, bathing the tassels in its light until they shimmered like mercury. Among the chiselled flecks of moonlight Father caught a whiff of the same sickly odour, far stronger than anything you might smell today. Commander Yu was leading him by the hand through the sorghum, where three hundred fellow villagers, heads pillowed on their arms, were strewn across the ground, their fresh blood turning the black earth into a sticky muck that made walking slow and difficult. The smell took their breath away. A pack of corpse-eating dogs sat in the field staring at Father and Commander Yu with glinting eyes. Commander Yu drew his pistol and fired — a pair of eyes was extinguished. Another shot, another pair of eyes gone. The howling dogs scattered, then sat on their haunches once they were out of range, setting up a deafening chorus of angry barks as they gazed greedily, longingly at the corpses. The odour grew stronger. ‘Jap dogs!’ Commander Yu screamed. ‘Jap sons of bitches!’ He emptied his pistol, scattering the dogs without a trace. ‘Let’s go, son,’ he said. The two of them, one old and one young, threaded their way through the sorghum field, guided by the moon’s rays.”

Mo Yan (Gaomi, 17 februari 1955)

Scene uit de gelijknamige film uit 1987

De Duitse schrijver Frederik Hetmann (eig. Hans-Christian Kirsch) werd geboren op 17 februari 1934 in Breslau. Zie ook alle tags voor Frederik Hetman op dit blog.

Uit :Ich habe sieben Leben. Die Geschichte des Ernesto Guevara, genannt Che

“Die Mutter, Celia de la Serna, wird als Mädchen »La Rebelda« genannt. Sie gilt als eine der schönsten und reichsten Erbinnen von Buenos Aires. Sie besitzt Tausende von Hektar Weideland und riesige Rinderherden. Sie ist mit 17 in Paris gewesen. Nach dem Tod ihrer Eltern hat sie einen Vormund und Anstandsdamen, wie sie die gesellschaftliche Konvention fordert, abgelehnt. Sie soll die erste Frau in Argentinien gewesen sein, die ein eigenes Bankkonto besaß. Sie trägt die Haare kurz geschnitten. Sie begeistert sich für marxistische Ideen.

In Argentinien verdient man in den 20er Jahren unseres Jahrhunderts das große Geld mit Fleisch. Die Gauchos reiten. Das Lasso fliegt. Staubwolken und Gitarrengeklimper. Aber wie ist es wirklich? Celia will es wissen.

Die Rinder werden in die Gasse getrieben. Am Ende der Gasse erwartet sie unverhofft der Tod: zwei Bolzen, die sich von der Seite her in den Schädel der Tiere bohren.

Celia beobachtet den Mann, der mit einem Fingerdruck diesen Bolzen betätigt. Ein gutmütiges Indianergesicht grinst sie an.

Die Kadaver treiben auf dem Fließband davon. Sie werden zerlegt, eingefroren oder in Dosen verpackt und nach Europa exportiert.

Celia sieht die Männer mit Sägen und blutverschmierten Schürzen umhergehen. Sie spürt den leicht süßlichen Geschmack von Blut auf der Zunge.

Am nächsten Tag erzählt man im Jockey Club, dem Treffpunkt der High Society von Buenos Aires, dass »La Rebelda« allein die Schlachthöfe besucht habe. Trotz, oder vielleicht gerade wegen solcher Launen, ist Celia umschwärmt von jungen Männern aus der Bohème und aus der Oberschicht. Zum Teufel mit diesen Gecken, die um sie schwänzeln und sich die Revolution als Operette vorstellen! Sie denkt an die Revolution als an eine große reinigende Kraft. Sie hasste die verhimmelnden Flirtworte blasierter Jünglinge, wenn sie allein mit einem von ihnen in der Nacht auf einer Terrasse steht und dazu schwere Colliers im Salon im Hintergrund klimpern … Oder war es ein Kronleuchter?“

Frederik Hetmann (17 februari 1934 – 1 juni 2006)

Cover

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 17e februari ook mijn vorige twee blogs van vandaag.