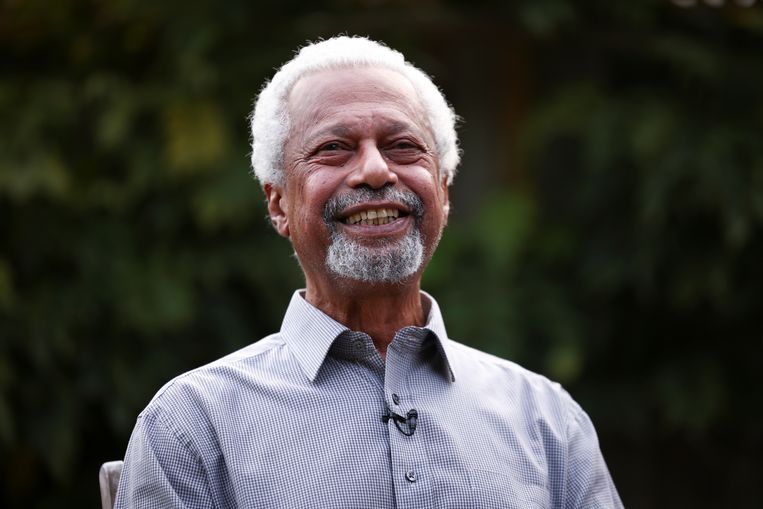

Nobelprijs voor Literatuur 2021 voor Abdulrazak Gurnah

De Tanzaniaanse schrijver Abdulrazak Gurnah ontvangt de Nobelprijs voor Literatuur 2021. Abdulrazak Gurnah werd geboren in Zanzibar op 20 december 1948. Gurnah groeide op in het toenmalige Britse protectoraat Zanzibar en ontvluchtte in 1967 de Revolutie van Zanzibar. Hij ging in 1968 studeren in Canterbury, eerst in een technische richting, maar stapte in 1971 over op literatuur. Hij schreef zijn proefschrift aan de Universiteit van Kent in 1982. Hij gaf van 1980 tot 1983 colleges aan de Bayero University Kano in Nigeria en keerde daarna terug naar Canterbury als hoogleraar Engelse en postkoloniale literatuur aan de Universiteit van Kent, waar hij in 2017 met emeritaat ging. Sinds 2006 is hij FRSL (fellow) van de Britse Royal Society of Literature. Gurnah schreef diverse boeken en artikelen over literatuur, met name over zaken rond kolonialisme en de verhoudingen tussen Afrika, India en het Westen. Hij levert sinds 1987 bijdragen aan het aan internationale literatuur gewijde Britse kwartaalschrift Wasafiri en publiceerde over schrijvers als V.S. Naipaul, Salman Rushdie, Wole Soyinka en Zoë Wicomb. Gurnah is een Engelstalig auteur. Hij schreef een tiental romans. De bekendste zijn “Memory of Departure” (1987), “Paradise” (1994) en “By the Sea” (2001). Dat laatste boek stond op de longlist van de Booker Prize en de shortlist van Los Angeles Times Book Award. Veel van zijn fictie is gesitueerd rond de Oost-Afrikaanse kustgebieden, waarbij zijn personages onderdeel deel zijn van een grotere wereld in verandering. Na emigratie mislukken deze jonge mannen doordat ze de aansluiting met hun nieuwe omgeving missen. Onbegrip, ongeloof, afwijzing en miscommunicatie door de taalbarrière zorgen steeds weer voor problemen. Vaak voelen ze zich ontworteld, vervreemd, ongewenst en beroofd van hun identiteit. Ze nemen de rol aan van slachtoffer, maar Gurnah laat zijn personages wel met ironie, humor en zelfrelativering reflecteren op de eigen situatie. De meest recente roman Abdulrazak Gurnah is “Afterlives” uit 2020.

Uit: Afterlives

“Khalifa was twenty-six years old when he met the merchant Amur Biashara. At the time he was working for a small private bank owned by two Gujarati brothers. The Indian-run private banks were the only ones that had dealings with local merchants and accommodated themselves to their ways of doing business. The big banks wanted business run by paperwork and securities and guarantees, which did not always suit local merchants who worked on networks and associations invisible to the naked eye. The brothers employed Khalifa because he was related to them on his father’s side. Perhaps related was too strong a word but his father was from Gujarat too and in some instances that was relation enough. His mother was a countrywoman. Khalifa’s father met her when he was working on the farm of a big Indian landowner, two days’ journey from the town, where he stayed for most of his adult life. Khalifa did not look Indian, or not the kind of Indian they were used to seeing in that part of the world. His complexion, his hair, his nose, all favoured his African mother but he loved to announce his lineage when it suited him. Yes, yes, my father was an Indian. I don’t look it, hey? He married my mother and stayed loyal to her. Some Indian men play around with African women until they are ready to send for an Indian wife then abandon them. My father never left my mother.

His father’s name was Qassim and he was born in a small village in Gujarat which had its rich and its poor, it’s Hindus and it’s Muslims and even some Hubshi Christians. Qassim’s family was Muslim and poor. He grew up a diligent boy who was used to hardship. He was sent to a mosque school in his village and then to a Gujarati-speaking government school in the town near his home. His own father was a tax collector who travelled the countryside for his employer, and it was his idea that Qassim should be sent to school so that he too could become a tax collector or something similarly respectable. His father did not live with them. He only ever came to see them two or three times in a year. Qassim’s mother looked after her blind mother-in-law as well as five children. He was the eldest and he had a younger brother and three sisters. Two of his sisters, the two youngest, died when they were small. Their father sent money now and then but they had to look after themselves in the village and do whatever work they could find. When Qassim was old enough, his teachers at the Gujarati-speaking school encouraged him to sit for a scholarship at an elementary English-medium school in Bombay, and after that his luck began to change. His father and other relatives arranged a loan to allow him to lodge as best he could in Bombay while he attended the school. In time his situation improved because he became a lodger with the family of a school friend, who also helped him to find work as a tutor of younger children. The few annas he earned there helped him to support himself.”