De Nederlandse dichter Ed Leeflang werd geboren op 21 juni 1929 in Amsterdam. Zie ook alle tags voor Ed Leeflang op dit blog.

Vakantiekolonie

Dertien boterhammen had de jongen gegeten;

hij mocht boven tachtig kinderen op tafel staan

en keek gelukkig in het rond. De zuster zei

dat je ook zoveel moest eten; dan ging bronchitis over,

want dan kwam je aan.

Dat je van heimwee aandrang krijgt

stond denkelijk niet in de handboeken.

Niet eens misprijzend schept de zuster

een natte hoop uit je spijlenbed;

’s middags moet je tot je moe wordt rusten.

Later zit je naast haar op het strand –

ze leest en doodgaan is hier verboden –

je wil niet scheppen, de zandvormen

van thuis zou je hier liever willen missen,

het rondje, de groene, het hartje, de rode.

Niet ver uit de kust spelen, op en onder.

de scholen bruinvissen. Daar is ook de echte

geheimzinnigheid van mooi weer.

Alleen op een vage feestdag is

bezoek van besluitelozen toegestaan.

Waar zullen ze eens met je heen gaan.

Als ze je na zes weken halen,

ben je niet aangekomen, wel plat gaan praten.

Nog eens weken zijn ze daar ongemakkelijk van

en tonen zich bedrogen en ontdaan.

De hazen

We waren in een weitje waar camille

het meeste te vertellen stond en hadden

een paal voor een waslijn in de grond gezet,

toen twee hazen uit het jonge koren dansten,

rechtop bewegend, in een aangrijpend menuet.

Dat kinderboekenhazen bleken te bestaan –

ze droegen dan wel geen parmante jassen,

maar hadden die aandoenlijke en overduidelijke

oren aan – het was zo schokkend als midden in

de goedheid of in de oudste angst voor donker

zijn te komen staan.

De schaamteloosheid van hun rondedans

en de driftige ernst van hun door

plotselinge versteningen onderbroken spel

deden ons de eigen argwanendheid en

verloren natuurlijkheid beseffen, dat

voelden wij aan onze sprakeloosheid wel.

Het voorjaar leek zelfs dreigend uit den boze

over de onschuld van de polder heen te hangen.

De dans duurde zo’n traag kwartier;

er was nog een kort leven om te blozen,

om naar de schoonheid van dit drieste dansen

te verlangen.

De Vlaamse dichter, schrijver en journalist Thomas Blondeau werd geboren in Poperinge op 21 juni 1978. Zie ook Zie ook alle tags voor Thomas Blondeau op dit blog

Uit: De Vaderlander

“Zoals

mensen als maagd kunnen sterven, kunnen ze leven zonder ook maar één

keer onderdeel te zijn geweest van iets meeslepends. Dat hoeft niet

betreurenswaardig te zijn. Kijk maar naar kloosterlingen die hun mond

niet kunnen houden over het genot van de berusting. Michel Quispel, de

vader van David, behoorde tot het slag mensen dat niet mist wat het niet

kent. Na een mislukte rechtenstudie was hij een paar jaar

handelsreiziger geweest in schoonmaakmiddelen. Het stoorde hem om zo’n

weinig mannelijk product te slijten, maar hij hield ervan onderweg te

zijn. Om zijn aangeboren verlegenheid te overwinnen, begon hij bier te

drinken. Zijn beroep gaf hem volop gelegenheid om vaak in cafés te zijn.

Wanneer hij een goede voormiddag had gehad, begon hij na twaalven met

drinken.

Later

begon hij ongeacht zijn voormiddag na twaalven te drinken. Na het

overlijden van zijn vader verkocht hij diens kruidenierswinkel en begon

een café dat hij De Vaderlander doopte. Genoemd naar de zandzakjes die

in de Eerste Wereldoorlog de wanden van de loopgraven tegen instorting

beschermden. Hij was zo trots op deze vondst dat hij jarenlang nieuwe

klanten vermoeide met zijn uitleg over het café als een wal tegen de

wereld.

‘David, hebt ge tegen uw vriend al gezegd waarom uw vader zijn café zo genoemd heeft?’

‘Ja, pa.’

‘Ik bedoel niet waar het vandaan komt maar wat het symboliseert?’

‘Ja, pa!’

Eigenlijk

zag David zijn vader alleen ’s ochtends bij het tandenpoetsen een glas

water drinken. Zijn dictum was: ‘’s Ochtends koffie om de dag goed in de

ogen te kijken en ’s middags een pint omdat het gezicht van de dag u

niet aanstaat.’ Hij was een gestaag drinker die nooit tot dronkenschap

verviel.

Hij

leefde zogezegd op een respectabele afstand van de realiteit. Die

afstand hield de middelmatige kwaliteit van zijn café, huwelijk en zijn

relatie met zijn zoon op een constant niveau. Geen uitzicht op

verbetering maar ook geen kans op verslechtering. Zijn alcoholisme en

omgang met klanten had hem een welwillende onverschilligheid gegeven.

Een manier van omgang die bestond uit glimlachen en het minimum aan

inspanning om een conversatie gaande te houden. Een manier van omgaan

die hij ook op zijn leven en gezin toepaste. Hij het David, die goede

cijfers haalde zonder noemenswaardige inspanning, meestal zijn gang

gaan. Geheel volgens zijn weinig uitgedachte filosofie dat het leven een

stroom is waar je wel kunt proberen iets aan te veranderen, maar wat

over het algemeen een nutteloze activiteit is want water stroomt toch

altijd naar het laagste punt.”

De Poolse dichter en essayist Adam Zagajewski werd geboren op 21 juni 1945 in Lwów, het huidige Lviv. Zie ook alle tags voor Adam Zagajewski op dit blog.

Night Is a Cistern

Night is a cistern. Owls sing. Refugees tread meadow roads

with the loud rustling of endless grief.

Who are you, walking in this worried crowd.

And who will you become, who will you be

when day returns, and ordinary greetings circle round.

Night is a cistern. The last pairs dance at a country ball.

High waves cry from the sea, the wind rocks pines.

An unknown hand draws the dawn’s first stroke.

Lamps fade, a motor chokes.

Before us, life’s path, and instants of astronomy.

Mysticism for Beginners

The day was mild, the light was generous.

The German on the café terrace

held a small book on his lap.

I caught sight of the title:

Mysticism for Beginners.

Suddenly I understood that the swallows

patrolling the streets of Montepulciano

with their shrill whistles,

and the hushed talk of timid travelers

from Eastern, so-called Central Europe,

and the white herons standing—yesterday? the day before?—

like nuns in fields of rice,

and the dusk, slow and systematic,

erasing the outlines of medieval houses,

and olive trees on little hills,

abandoned to the wind and heat,

and the head of the Unknown Princess

that I saw and admired in the Louvre,

and stained-glass windows like butterfly wings

sprinkled with pollen,

and the little nightingale practicing

its speech beside the highway,

and any journey, any kind of trip,

are only mysticism for beginners,

the elementary course, prelude

to a test that’s been

postponed.

Vertaald door Clare Cavanagh

De Canadese dichteres, essayiste en vertaalster Anne Carson werd geboren op 21 juni 1950 in Toronto. Zie ook alle tags voor Anne Carson op dit blog.

The Glass Essay

I

of the man who

left in September.

His name was Law.

My face in the bathroom mirror

has white streaks down it.

I rinse the face and return to bed.

Tomorrow I am going to visit my mother.

SHE

She lives on a moor in the north.

She lives alone.

Spring opens like a blade there.

I travel all day on trains and bring a lot of books—

some for my mother, some for me

including The Collected Works Of Emily Brontë.

This is my favourite author.

Also my main fear, which I mean to confront.

Whenever I visit my mother

I feel I am turning into Emily Brontë,

my lonely life around me like a moor,

my ungainly body stumping over the mud flats with a look of transformation

that dies when I come in the kitchen door.

What meat is it, Emily, we need?

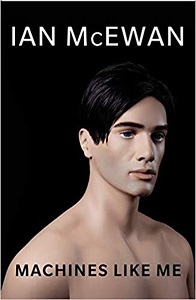

De Britse schrijver Ian McEwan werd op 21 juni 1948 geboren in de Engelse garnizoensplaats Aldershot. Zie ook alle tags voor Ian McEwan op dit blog.

Uit:Machines Like Me

“He

stood before me, perfectly still in the gloom of the winter’s

afternoon. The debris of the packaging that had protected him was still

piled around his feet. He emerged from it like Botticelli’s Venus rising

from her shell. Through the north-facing window, the diminishing light

picked out the outlines of just one half of his form, one side of his

noble face. The only sounds were the friendly murmur of the fridge and a

muted drone of traffic. I had a sense then of his loneliness, settling

like a weight around his muscular shoulders. He had woken to find

himself in a dingy kitchen, in London SW9 in the late twentieth century,

without friends, without a past or any sense of his future. He truly

was alone. All the other Adams and Eves were spread about the world with

their owners, though seven Eves were said to be concentrated in Riyadh.

As I reached for the light switch I said, ‘How are you feeling?’

He looked away to consider his reply. ‘I don’t feel right.’

This time his tone was flat. It seemed my question had lowered his spirits. But within such microprocessors, what spirits?

‘What’s wrong?’

‘I don’t have any clothes. And—’

‘I’ll get you some. What else?’

‘This wire. If I pull it out it will hurt.’

‘I’ll do it and it won’t hurt.’

But

I didn’t move immediately. In full electric light I was able to observe

his expression, which barely shifted when he spoke. It was not an

artificial face I saw, but the mask of a poker player. Without the

lifeblood of a personality, he had little to express. He was running on

some form of default program that would serve him until the downloads

were complete. He had movements, phrases, routines that gave him a

veneer of plausibility. Minimally, he knew what to do, but little else.

Like a man with a shocking hangover.

I

could admit it to myself now – I was fearful of him and reluctant to go

closer. Also, I was absorbing the implications of his last word. Adam

only had to behave as though he felt pain and I would be obliged to

believe him, respond to him as if he did. Too difficult not to. Too

starkly pitched against the drift of human sympathies. At the same time I

couldn’t believe he was capable of being hurt, or of having feelings,

or of any sentience at all. And yet I had asked him how he felt. His

reply had been appropriate, and so too my offer to bring him clothes.

And I believed none of it. I was playing a computer game. But a real

game, as real as social life, the proof of which was my heart’s refusal

to settle and the dryness in my mouth.”

Cover

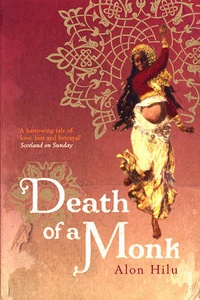

De Israëlische schrijver Alon Hilu werd geboren op 21 juni 1972 in Jaffa. Zie ook alle tags voor Alon Hilu op dit blog.

Uit: Death of a Monk

“There were long-sleeved dresses adorned with feathers, and dresses ornamented with shiny beads and shells, and I would draw the choice cloths to my chest and inhale their fragrance, and when Maman was certain that no evil eyes were watching us, waiting to tell Father about our forbidden acts, she would remove the brooch pinning up her tresses in one swift motion, freeing her hair to flow to her waist, and then she would remove my tunic, momentarily fearful of my naked body dotted with the mysterious pores, and she would wrap me in an evening gown of her own choosing, a gown that covered my legs all the way to the toes and twisted around my arms and, in order to enhance the excitement, she would slip a pair of black, patent-leather shoes over my small feet with the disputatious toes, commanding me to sit upon her bed while she passed a variety of powders and coloured lotions over my face, after which I would stand before her glowing visage. Not a soul knew of the garments I would don from time to time, not even the servants toiling in our home. Once, only once, while we were under the mistaken impression that he was off somewhere tending to one of his numerous business concerns, Father returned home early. His shoes hammered the marble floor as he rounded the fish pond, while Maman rushed frantically to strip me of my gown and remove the spots of makeup, almost ripping the expensive fabrics from my body so that Father would not catch us in our misconduct, and when he entered and found me in the room, sitting upon his bed, he grabbed hold of me at once by the forearm and faced us, awaiting our explanation. She would not grant me the wink of an eye confirming our complicit secret, not even the quickest flash of mischief between conspirators: Maman rushed to inform him of my conduct during his absence, how I had come to her and bothered her and recited coarse poetry to her learned from the boys at the Talmud Torah, how I was uncouth and uncultured, more evil even than the wild Bedouin who plundered our caravans, and that my place was not in the pampering bedroom of my childhood, but in the prison dungeon beneath the Saraya fortress, seat of the governor of Damascus, where the cries of tortured prisoners could be heard each night.”

Cover

De Franse schrijver Jean Paul Sartre werd geboren op 21 juni 1905 in Parijs. Zie ook alle tags voor Jean-Paul Sartre op dit blog.

Uit: Le Mur

«

On nous poussa dans une grande salle blanche, et mes yeux se mirent à

cligner parce que la lumière leur faisait mal. Ensuite, je vis une table

et quatre types derrière la table, des civils, qui regardaient des

papiers. On avait massé les autres prisonniers dans le fond et il nous

fallut traverser toute la pièce pour les rejoindre. Il y en avait

plusieurs que je connaissais et d’autres qui devaient être étrangers.

Les deux qui étaient devant moi étaient blonds avec des crânes ronds,

ils se ressemblaient : des Français, j’imagine. Le plus petit remontait

tout le temps son pantalon : c’était nerveux.

Ça

dura près de trois heures ; j’étais abruti et j’avais la tête vide mais

la pièce était bien chauffée et je trouvais ça plutôt agréable : depuis

vingt-quatre heures, nous n’avions pas cessé de grelotter. Les gardiens

amenaient les prisonniers l’un après l’autre devant la table. Les

quatre types leur demandaient alors leur nom et leur profession. La

plupart du temps ils n’allaient pas plus loin – ou bien alors ils

posaient une question par-ci, par-là : “As-tu pris part au sabotage des

munitions ?” Ou bien : “Où étais-tu le matin du 9 et que faisais-tu ?”

Ils n’écoutaient pas les réponses ou du moins ils n’en avaient pas l’air

: ils se taisaient un moment et regardaient droit devant eux puis ils

se mettaient à écrire. Ils demandèrent à Tom si c’était vrai qu’il

servait dans la Brigade internationale : Tom ne pouvait pas dire le

contraire à cause des papiers qu’on avait trouvés dans sa veste. À Juan

ils ne demandèrent rien, mais, après qu’il eut dit son nom, ils

écrivirent longtemps.

“C’est

mon frère José qui est anarchiste, dit Juan. Vous savez bien qu’il

n’est plus ici. Moi je ne suis d’aucun parti, je n’ai jamais fait de

politique”.

Ils ne répondirent pas. Juan dit encore :

“Je n’ai rien fait. je ne veux pas payer pour les autres”.

Ses lèvres tremblaient. Un gardien le fit taire et l’emmena. C’était mon tour :

“Vous vous appelez Pablo lbbieta ?”

Je dis que oui.

Le type regarda ses papiers et me dit :

“Où est Ramon Gris ?”

– Je ne sais pas.”

De Amerikaanse dichter, uitgever en kunsthandelaar Stanley Moss werd geboren in Woodhaven, New York op 21 juni 1925. Zie ook alle tags voor Stanley Moss op dit blog.

Psalm

God of paper and writing, God of first and last drafts,

God of dislikes, god of everyday occasions—

He is not my servant, does not work for tips.

Under the dome of the roman Pantheon,

God in three persons carries a cross on his back

as an aging centaur, hands bound behind his back, carries Eros.

Chinese God of examinations: bloodwork, biopsy,

urine analysis, grant me the grade of fair in the study of dark holes,

fair in anus, self-knowledge, and the leaves of the vagina

like the pages of a book in the vision of Ezekiel.

May I also open my mouth and read the book by eating it,

swallow its meaning. My Shepherd, let me continue to just pass

in the army of the living,

keep me from the ranks of the excellent dead.

It’s true I worshiped Aphrodite

who has driven me off with her slipper

after my worst ways pleased her.

I make noise for the Lord.

My Shepherd, I want, I want, I want.

Bright Day

I sing this morning: Hello, hello.

I proclaim the bright day of the soul.

The sun is a good fellow,

the devil is a good guy, no deaths today I know.

I live because I live. I do not die because I cannot die.

In Tuscan sunlight Masaccio

painted his belief that St. Peter’s shadow

cured a cripple, gave him back his sight.

I’ve come through eighty-five summers. I walk in sunlight.

In my garden, death questions every root, flowers reply.

I know the dark night of the soul

does not need God’s eye,

as a beggar does not need a hand or a bowl.

De Braziliaanse schrijver Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis werd geboren in Rio de Janeiro op 21 juni 1839. Zie ook alle tags voor Machado de Assis op dit blog.

Uit: The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (Vertaald door Gregory Rabassa)

“Now that I’ve mentioned my two uncles, let me make a short genealogical outline here.

The

founder of my family was a certain Damiao Cubas, who flourished in the

first half of the eighteenth century. He was a cooper by trade, a native

of Rio de Janeiro, where he would have died in penury and obscurity had

he limited himself to the work of barrel-making. But he didn’t. He

became a farmer. He planted, harvested, and exchanged his produce for

good, honest silver patacas until he died, leaving a nice fat

inheritance to a son, the licentiate Luis Cubas. It was with this young

man that my series of grandfathers really begins–the grandfathers my

family always admitted to–because Damiao Cubas was, after all, a

cooper, and perhaps even a bad cooper, while Luis Cubas studied at

Coimbra, was conspicuous in affairs of state, and was a personal friend

of the viceroy, Count da Cunha.

Since

the surname Cubas, meaning kegs, smelled too much of cooperage, my

father, Damiao’s great-grandson, alleged that the aforesaid surname had

been given to a knight, a hero of the African campaigns, as a reward for

a deed he brought off: the capture of three hundred barrels from the

Moors. My father was a man of imagination; he flew out of the cooperage

on the wings of a pun. He was a good character, my father, a worthy and

loyal man like few others. He had a touch of the fibber about him, it’s

true, but who in this world doesn’t have a bit of that? It should be

noted that he never had recourse to invention except after an attempt at

falsification. At first he had the family branch off from that famous

namesake of mine, Captain-Major Brás Cubas, who founded the town of Sao

Vicente, where he died in 1592, and that’s why he named me Brás. The

captain-major’s family refuted him, however, and that was when he

imagined the three hundred Moorish kegs.

A

few members of my family are still alive, my niece Venancia, for

example, the lily of the valley, which is the flower for ladies of her

time. Her father, Cotrim, is still alive, a fellow who … But let’s not

get ahead of events. Let’s finish with our poultice once and for all.“

Cover

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 21e juni ook mijn blog van 21 juni 2014 deel 1, en deel 2 en eveneens deel 3.