Dolce far niente

At the Gym

This salt-stain spot

marks the place where men

lay down their heads,

back to the bench,

and hoist nothing

that need be lifted

but some burden they’ve chosen

this time: more reps,

more weight, the upward shove

of it leaving, collectively,

this sign of where we’ve been:

shroud-stain, negative

flashed onto the vinyl

where we push something

unyielding skyward,

gaining some power

at least over flesh,

which goads with desire,

and terrifies with frailty.

Who could say who’s

added his heat to the nimbus

of our intent, here where

we make ourselves:

something difficult

lifted, pressed or curled,

Power over beauty,

power over power!

Though there’s something more

tender, beneath our vanity,

our will to become objects

of desire: we sweat the mark

of our presence onto the cloth.

Here is some halo

the living made together.

Maryville

De Engelse dichter en schrijver Ted Hughes werd geboren op 17 augustus 1930 in Mytholmroyd, Yorkshire. Zie ook alle tags voor Ted Hughes op dit blog

The Jaguar

The apes yawn and adore their fleas in the sun.

The parrots shriek as if they were on fut, or strut

Like cheap tarts to attract the stroller with the nut.

Fatigued with indolence, tiger and lion

Lie still as the sun. The boa-constrictor’s coil Is a fossil.

Cage after cage seems empty, or

Stinks of sleepers from the breathing straw.

It might be painted on a nursery wall.

But who runs like the rest past these arrives

At a cage where the crowd stands, stares, mesmerized,

As a child at a dream, at a jaguar hurrying enraged

Through prison darkness after the drills of his eyes

Cat And Mouse

On the sheep-cropped summit, under hot sun,

The mouse crouched, staring out the chance It dared not take.

Time and a world

Too old to alter, the five mile prospect—

Woods, villages, farms—hummed its heat-heavy

Stupor of life.

Whether to two

Feet or four, how are prayers contracted!

Whether in God’s eye or the eye of a cat.

To Paint A Waterlily

A green level of lily leaves

Roofs the pond’s chamber and paves

The flies’ furious arena: study

These, the two minds of this lady.

First observe the air’s dragonfly

That eats meat, that,bullets by

Or stands in space to take aim;

Others as dangerous comb the hum

Under the trees. There are battle-shouts

And death-cries everywhere hereabouts

But inaudible, so the eyes praise

To see the colors of these flies

De Britse schrijver Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul werd geboren op 17 augustus 1932 in Chaguanas, Trinidad en Tobago. Zie ook alle tags voor V. S. Naipaul op dit blog. V. S. Naupaul stierf op 11 augustus jongstleden op 85-jarige leeftijd.

Uit: A Bend In the River

” It is true.’

He was born in Trinidad in 1932, but Port of Spain and the Caribbean would never become home: the fastidious and ambitious young man found his extended Indian family unbearable. ‘I had to get away,’ he says. So he arrived in England a triple exile: from India, from Trinidad, and from his flesh and blood. ‘It was a pretty awful childhood,’ he remembers. ‘The Trinidad side was nice, but the family I was born into … terrible, terrible. It was very large, with too many people. There was no beauty. It was full of malice. No thought, no beauty. These are things that mattered a lot to me, even when I was young.’

Then there was the unresolved business of his literary ambition. Naipaul has never made any secret of the fact that, from the age of 11, ’the wish came to me to be a writer’, a wish that was soon ‘a settled ambition’, even if, as he now says, it was also ‘a kind of sham’. In books and writing, he could master the chaos of his inheritance, soothe the raucous interruptions of the familial past – and find an identity.

But here was another obstacle in the writer’s path to himself. ‘I wished to be a writer,’ he remarks in one of his essays. ‘But together with the wish there had come the knowledge that the literature that had given me the wish came from another world, far away from our own.’ Naipaul somehow had to find his voice in English, and to find it in an idiom that did not mimic the imperial masters or compromise his authenticity. Summarising his 50-year search for literary truth, he has expressed it as ‘disorder within, disorder without’.

The English books of his school, the best years of his childhood, he says, offered the powerful fantasy of a remote and mysterious world, Dickens’s London or Wordsworth’s Lakeland, for example. But to a thoughtful and sensitive young man, for whom literature was a salvation, English both worked and did not work. ‘I couldn’t understand the settings,’ he says. Dickens’s ‘rain’ was never a tropical downpour, his ‘snow’ was unimaginable, and how could Naipaul relate to daffodils he had never seen?

For the ‘fraudulent’ Indian, uniquely sensitive to his place in the world, the jux-taposition of a full-blown imperial English culture with the ‘formless, unmade society’ of a small Caribbean island was only a source of panic and uncertainty, especially if it was your deepest ambition to use this language to write about, and make sense of, the world in which you were growing up. ‘I might adapt Dickens to Trinidad,’ Naipaul has written, ‘but it seemed impossible that the life I knew in Trinidad could be turned into a book.’

De Duitse schrijver en theatermaker Nis-Momme Stockmann werd geboren op 17 augustus 1981 in Wyk auf Föhr.Zie ook alle tags voor Nis-Momme Stockmann op dit blog.

Uit: Der Fuchs

«Du hast eine Notfallkiste … mit einer waffenscheinpflichtigen Waffe auf dem Dach … aber kein … Wasser?» «Wasser», wiederholte Dogge, als sei das Wort ein sumerisches Rätsel, und lud die Flinte.

Jütte setzte sich, ernst und dunkel funkelnd, auf die andere

Seite des Daches und schaute in Richtung Sonne. So viel Licht.

Eine Millionen Lumen. Eine Milliarde, Trilliarde Lumen. Eine Welt aus Wasser und Licht. Nur hinter dem Schornstein war ein blasser Schatten, um den sich ein paar erschöpfte Krähen stritten. Ich hatte Krämpfe in den Augenlidern. Saurer Schweiß lief mir von der Stirn. Als das Licht langsam rot wurde, wusste ich zuerst nicht, ob mir die Augen bluteten oder es tatsächlich endlich Abend war. Ist das eine Sonne oder eine glühende Zigarre, die uns ein boshafter Gott aus Langeweile an die Stirn drückte, während er uns beim Schmelzen zusah? Ich hatte das Gefühl, wir wären schon ewig auf dem Dach. Aber nein, es waren ja nur wenige Stunden. Hatten wir einen Tag übersprungen? Über den Untiefen des Hochwassers zogen graue Wolken in eigenartigen Formationen auf – irgendeine Kraft ließ sie schwer hin und her taumeln, wie ein betrunkener Mann. Tonnen von Insektenleibern – Millionen ihre Auferstehung feiernde Mücken, Käfer, Motten. Ich stellte mir vor, was Dogge wohl unternehmen würde mit seiner Schrotflinte, wenn die jetzt gesammelt auf uns zufliegen würden. Als hätte er meinen Gedanken gehört, stieß er einen besoffenen Kampfschrei aus und schoss in die Luft. «Danke, Dogge, und herzlichen Glückwunsch», sagte Jütte, «zehn Jahre Konzerte ohne Hörschutz haben’s nicht geschafft, dafür musste nur mal ein Vollidiot, mit dem ich auf einem Dach festsitze, grundlos eine Waffe abfeuern.» Dogge verbeugte sich. «Dieser Scheiß ist gefährlich!»

Ein Kind weinte in der Ferne. Etwa 200 Meter von uns und noch weiter von den meisten anderen Häusern entfernt entdeckten wir es in der Krone eines schrägstehenden Baums. Absolut unerreichbar. Dogge war hin über. Schielte schon. Und sah mindestens 15 Jahre älter aus, als er war (was bei seinen 33 Jahren wirklich eine erstaunliche Verfallsleistung im Zusammenspiel von Sonne und Alkohol bedeutete). Er hatte noch einen Flachmann in seiner Jackeninnentasche, aus dem er ständig kleine Schlucke nahm. Aber das bemerkten wir erst viel zu spät. Er feuerte noch einmal. Dahinten traf er mit einem müden Puff ins Wasser, nicht mehr, als würde man in ein Kissen schlagen. «Baumann!», schrie Jütte.

Vorne, wo Frau Garres vor ihrem Schlaganfall gewohnt hatte, schoss er eine schöne, ebenförmige Tonsur in einen Baum, und 20 Meter vor uns und zu unserer großen Überraschung, denn die Schrotflinte machte etwa untertassengroße Schleifen vor seinem Gesicht, traf er einen Hund, exakt in die Flanke. Er ging sofort, nachdem ihm der Hinterleib explodiert war, ohne Jaulen oder irgendwas, unter, so plötzlich und lautlos, dass ich unweigerlich lachen musste – «Vorm Ertrinken gerettet», sagte Dogge sehr ernst.“

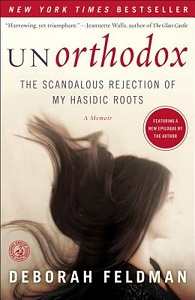

De Amerikaanse schrijfster Deborah Feldman werd geboren op 17 augustus 1986 in de chassidische gemeenschap van Satmar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York. Zie ook alle tags voor Deborah Feldman op dit blog.

Uit: Unorthodox

“Í avoided the gaze of passersby, terrified of running into a suspicious neigh-bor. What if someone asked me what I was carrying? I skirted young boys careening by on shabby bicycles and teenagers pushing their younger siblings in squeaky-wheeled prams. Everyone was outside on this balmy spring day, and the last half block seemed to take forever. At home I rushed to hide the book under my mattress, pushing it all the way in just in case. I smoothed the sheets and blankets and draped the bedspread so that it hung to the floor. I sat down at the edge of the bed and felt guilt wash over me so suddenly that the strength of it kept me pinned there. I wanted to forget that this day had ever happened. All through Shabbos the book burned beneath my mattress, alternately chastising me and beckoning to me. I ignored the call; it was too dangerous, there were too many people around. What would Zeidy say if he knew? Even Bubby would be horrified, I knew. Sunday stretches ahead of me like an unopened krepela, a soft, doughy day encapsulating a secret filling. All I have to do is help Bubby with the cooking, then I will have the rest of the afternoon free to spend as I please. Bubby and Zeidy have been invited to a cousin’s bar mitzvah today, which means I will have at least three hours of uninterrupted pri-vacy. There is still a slab of chocolate cake in the freezer that I’m sure Bubby, with her spotty memory, won’t miss. Could this afternoon get any better? After Zeidy’s heavy footfalls fade down the stairs, and I watch from my second-floor bedroom window as my grandparents get into the taxi, I slide the book out from under the mattress and place it reverently on my desk. The pages are made of waxy, translucent paper, and they are each packed with text: the original words of the Talmud as well as the English translation, and the rabbinical discourse that fills up the bottom half of each page. I like the discussions best, records of the conversations the ancient rabbis held about each holy phrase in the Talmud. On the sixty-fifth page the rabbis are arguing about King David and his ill-gotten wife Bathsheba, a mysterious biblical tale about which I’ve always been curious. From the fragments mentioned, it appears that Bathsheba was already married when David laid his eyes upon her, but he was so attracted to her that he deliberately sent her husband, Uriah, to the front lines so that he would be killed in war, leaving Bathsheba free to remarry. Afterward, when David had finally taken poor Bathsheba as his lawful wife, he looked into her eyes and saw in the mirror of her pupils the face of his own sin and was repulsed. After that, David refused to see Bathsheba again, and she lived the rest of her life in the king’s harem, ignored and forgotten. I now see why I’m not allowed to read the Talmud. My teachers have always told me, “David had no sins. David was a saint. It is forbidden to cast aspersions on God’s beloved son and anointed leader.”

De Nederlandse dichter en journalist Wim Hijmans werd geboren in Groningen op 27 augustus 1926. Zie ook alle tags voor Wim Hijmans op dit blog.

Uit: Het algemeen belang en de televisie

‘Zo dient… het verlangen van het bedrijfsleven naar het toelaten van het element reclame in de televisie door de overheid ook slechts op gronden, aan het algemeen belang ontleend, te worden beoordeeld.’

Staatssecretarissen Scholten en Veldkamp in de Nota inzake Reclametelevisie.

Het debat over de vraag, of Nederland in de toekomst reclameboodschappen moet toelaten in de televisie, is al jaren gaande. Het is door het verschijnen van de Nota inzake Reclametelevisie op 22 februari van dit jaar in een nieuw, een officiëler stadium gekomen, en het is daarom wellicht dienstig, bij onze kanttekeningen over dit onderwerp allereerst een korte analyse te geven van de posities, waarin de deelnemers aan de discussie zich op het ogenblik der verschijning bevonden.

De Nederlandse omroep heeft zich, van zijn prilste (radio-)tijd af, bewogen in een emotionele sfeer. De omroepverenigingen dienden zich sekte-gewijs aan; van een nationale radio-omroep was geen sprake, ook al omdat hij eenvoudigweg niet paste in de politiek der vooroorlogse regeringen, die zich hielden aan een variant op Thorbecke: dat cultuur (en daaronder behoort men de omroep te rangschikken) geen overheidstaak is. De eenheid, die de oorlog de Nederlanders scheen te geven, bleek àl te tijdelijk: pogingen om Radio Nederland in Overgangstijd om te zetten in een permanente nationale omroep, mislukten jammerlijk. Men mag dat betreuren – maar de feiten waren zo, toen de televisie in 1951 uit de sfeer van het industriële experiment (Philips) in die van het officiële werd gebracht. De omroepverenigingen, uitgaande van de simpele veronderstelling dat ether en ether hetzelfde is, claimden en kregen het televisie-monopolie. Ook dat mag men achteraf betreuren als een beschikking, die meer door gemakzucht dan door kennis van zaken werd ingegeven – maar ook hier heeft men te maken met een feit.”

Groningen