De Estische dichter, schrijver en vertaler Tõnu Õnnepalu werd geboren op 13 september 1962 in Tallin. Zie ook alle tags voor Tõnu Õnnepalu op dit blog.

Uit: Flanders Diary (Vertaald door Miriam McIlfatrick)

“More Chinese vases in windows, gnomes in gardens, appliances in kitchens? Well, all right, but if you already have Chinese vases, gnomes and a whole range of appliances, then perhaps you no longer notice the difference. Home appliances can of course be replaced by new ones and in recent times you have to do so frequently, because they tend to break down increasingly quickly and no one repairs them any more. And then the new machine has some extra programme, which means that it will break even more quickly, but of course it does the same thing as before, it boils, it cooks or it washes.

Formerly, the humanists thought that if a person is freed from hard and degrading physical labour, he will devote himself to poetry, art, philosophy, philanthropy and self-improvement. This proved to be a miscalculation, because it departed from a false premise. Considering physical work hard and degrading was simply a biblical, ecclesiastical and aristocratic prejudice. The humanists could just have looked around to see whether or not those who already had been, and had been from one generation to the next, freed from that hard and degrading curse (to earn the bread they ate by the sweat of their brow), had devoted themselves to poetry and philosophy or predominantly to something else instead. Education certainly makes people better. But only a little. And even that is not really certain. A comfortable life makes people better because it is more comfortable not to bother with other people if you have everything you need. There is just no knowing to what extent this advantage will remain if the assumption, i.e. comfort, is removed. We have not seen that yet, but we probably will, those of us who are spared long enough.

I do not know when the idea originated in mankind that life should keep getting better. Some people blame the creation of this precondition for a belief in progress, like everything else by the way, on Christianity, because it replaced the old cyclical perception of time (that everything repeats and returns like the seasons, the moon and the sun in their circuits) with finiteness, with the conception of the end of time, towards which we are moving. In fact, this notion that we are m o v i n g in that direction may only have developed in the course of many centuries; initially, the return of Christ was imminently expected, even within the same generation. It did not matter that it was already several tens of generations since it was first anticipated. It is common knowledge that wherever you are, in a field or in bed, alone or in a crowd, right there and then that hour will strike you.”

Tõnu Õnnepalu (Tallin, 13 september 1962)

De Britse schrijver Roald Dahl werd geboren op 13 september 1916 in Llandalf, Zuid-Wales. Zie ook alle tags voor Roald Dahl op dit blog.

Uit: Matilda

“Matilda’s brother Michael was a perfectly normal boy, but the sister, as I said, was something to make your eyes pop. By the age of one and a half her speech was perfect and she knew as many words as most grown-ups. The parents, instead of applauding her, called her a noisy chatterbox and told her sharply that small girls should be seen and not heard.

By the time she was three, Matilda had taught herself to read by studying newspapers and magazines that lay around the house. At the age of four, she could read fast and well and she naturally began hankering after books. The only book in the whole of this enlightened household was something called Easy Cooking belonging to her mother, and when she had read this from cover to cover and had learnt all the recipes by heart, she decided she wanted something more interesting.

“Daddy,” she said, “do you think you could buy me a book?”

“A book?” he said. “What d’you want a flaming book for?”

“To read, Daddy.”

“What’s wrong with the telly, for heaven’s sake? We’ve got a lovely telly with a twelve-inch screen and now you come asking for a book! You’re getting spoiled, my girl!”

Nearly every weekday afternoon Matilda was left alone in the house. Her brother (five years older than her) went to school. Her father went to work and her mother went out playing bingo in a town eight miles away. Mrs Wormwood was hooked on bingo and played it five afternoons a week. On the afternoon of the day when her father had refused to buy her a book, Matilda set out all by herself to walk to the public library in the village. When she arrived, she introduced herself to the librarian, Mrs Phelps. She asked if she might sit awhile and read a book. Mrs Phelps, slightly taken aback at the arrival of such a tiny girl unaccompanied by a parent, nevertheless told her she was very welcome.

“Where are the children’s books please?” Matilda asked.

“They’re over there on those lower shelves,” Mrs Phelps told her. “Would you like me to help you find a nice one with lots of pictures in it?”

“No, thank you,” Matilda said. “I’m sure I can manage.”

Roald Dahl (13 september 1916 – 23 november 1990)

De Poolse schrijver Janusz Glowacki werd geboren op 13 september 1938 in Poznań. Zie ook alle tags voor Janusz Glowacki op dit blog.

Uit: Antigone in New York (Vertaald door Joan Torres)

« ANITA: “Can I ask you just one thing? Are you sure he’s dead? Because so many things could happen around here. I mean, he could have just passed out or something or fallen asleep under something where no one could see him. He could have gotten drunk. Are you absolutely sure? Because sometimes people get confused and think they see one thing but really it’s something else. You have to be one hundred percent sure…,The Indian told me the ambulance took him too but I don’t trust him. He’s always lying. You know what I mean?…. (weeping into her hands) I knew it. It was that cashmere sweater. I let it get to me. I knew it was bad luck but I took it anyway. They were giving it away and I just couldn’t leave it there. This sweater belonged to some unhappy person. Happy people don’t wear cashmere sweaters but unhappy people, they are either too cold or too hot and instead of going to the doctor they buy a cashmere sweater and when they put it on they start sweating right away and then their sweat goes into the cashmere and their bad luck sticks to it. You can wash it. You can even dry clean it but it won’t do any good. The bad luck stays in the sweater no matter what you do. (she drinks the cold coffee and throws the empty cup into the trash basket) If you have to wear a cashmere sweater it’s best to get one with shoulder pads in it because that’s where the bad luck collects. Then you can just pull out the pads and throw them away. That helps. I did that right away but it just wasn’t enough. I felt it when I got it. But now it’s too late. (weeps more, and opens her coat to show him). See? This is acryllic. And Acryllic is no problem. You just take it off and shake it off and shake it a couple of times (she demonstrates) and the bad luck disappears. (praying again). What am I going to do?”

Janusz Glowacki (Poznań, 13 september 1938)

Scene uit een opvoering in Warschau,1993

De Nederlandse dichter, schrijver en schilder Jacobus (Jac) van Looy werd geboren in Haarlem op 13 september 1855. Zie ook alle tags voor Jac. van Looy op dit blog.

Uit: Jaapje

“Hij was nog maar zes en een verreljaar en Koos was al ouwer dan elf. Hij hoorde Koos haar neus ophalen; ze kneep zijn hand zoo hard, en hij wou wel die doek wat weg doen.

‘Je hoeft beslist zoo hard niet te loopen,’ zei Koos, ‘we zij-ne er gauw.’

Ze had het nauwelijks gezegd of de steeg stond wijd naast hen open en daar was een heel groot licht. Jaapje dacht heelemaal niet meer aan Bies, dat was nu net zoo licht als het raam van de school, toen ze achter elkaâr over de plaats naar de kerstboom waren gegaan. Plotseling liepen de kinderen in het licht der ramen van Bies en stonden op de spiegeling er van in de straat.

‘Wat een beesten van hartekoeken,’ riep Koos uit de kap van haar mantel.

Jaapjes mond gaapte open van de heerlijkheid. Hij zag allemaal, allemaal, vlaggen allemaal. Het raam was niet het raam van de winkel, het was een ander raam. Jaapje kon over de kozijn-drempel net naar binnen kijken en daar stond het allemaal. Koos had hem losgelaten, maar hij greep haar bij haar tabbert, want Jaapje was niets op zijn gemak. Hij wist van kleuren niet veel, maar als hij van de zomer een glaasie had kunnen vinden, plakte hij met spuug dat vol blaadjes van bloemen, die bij de moeder uit het hekje vielen, dan vouwde je daar een pampiertje om en maakte een deurtje in het pampiertje en dan liet je het zien voor een griffie of voor een speld. Jaapje wist dus heel goed wat mooi was.

‘Nou mot je goed kijken,’ maande Koos, ‘dan kan je straks zeggen wat je hebben wil.’

‘Wat een kéurige tafel,’ riep ze hartgrondig.

‘Dan gaan we er maar in,’ zei ze, omdat Jaapje geen woord liet hooren.

‘En nou ga je me niet huilen, hoop ik.’

Jaapje hield zich goed aan Koos’ mantel vast en beiden gingen ze door de winkeldeur, die of er geen deur was, stond open. En nu was de kamer weg en herkende hij de toonbank; het rookte; allemaal koek met blink en sokkelaë letters; hij zag een A, hij zag een B, hij zag een J, Jaapje ging al op school. Bies stond bij de weegschaal, kraak in ’t wit, in zijn boterbanketlucht en vanielje-geuren; een platte witte muts was op zijn hoofd en hij lachte met zijn zwarte tanden. Jaapje kende hem toch wel, al had hij hem nooit gezien zoo. Hij kreeg poppetjes voor zijn oogen, want Koos had omgedraaid en daar was weêr de kamer met vlaggen.

Koos had zich dadelijk los van hem gemaakt, schoof tusschen de menschen door, van de eene naar de andere, terwijl het ventje in een leêge plek, midden voor de tafel was gaan staan en de toppen van zijn kleume handen, of wou hij zich op gaan tillen, klemde om den rand van het schoone Iaken dat eigenlijk papier was.”

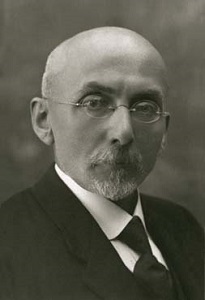

Jac. van Looy (13 september 1855 – 24 februari 1930)

Fotoportret door Willem Witsen, 1891

De Nederlandse dichter, predikant en hoogleraar Nicolaas Beets (pseudoniem: Hildebrand) werd geboren op 13 september 1814 in Haarlem. Zie ook alle tags voor Nicolaas Beets op dit blog.

Uit: Camera Obscura

“En zijn gezin en buren, om den haard vergaderd, hooren met belangstelling en welgevallen nog eens naar de oude jachtfeiten, van de drie hoenders met de twee loopen, en de twee eenden in één schot! – Komen ook de boeren niet betalen, en daarbij hunne huislijke zaken openleggen? En komt de dominé niet om een partij te schaken? En schrijft gij zelf, daar binnen de muren, geen boeken genoeg voor hem? En krijgt hij niet tweemaal in de week een heel pak couranten, waarin hij tot zijn groote stichting leest van de bezoeken van koningen en prinsessen in de hoofdstad; van tabliers van diamanten en toiletten van goud, van acteurs die uitmunten in hun nieuwe rol; van groote, grootere, grootste, allergrootste, en extra allergrootste virtuozen; van stikvolle zalen, schitterende kapsels, en onvermengd kunstgenot; van plumbeering van holle tanden die hij niet noodig heeft, en “Source de vie, Levensbron,” à f 1.25 de doos, die hij nog beterkoop heeft op het land, met en benevens de harrewarrerijen over boeken-schrijven, waar hij zich niet aan bezondigt, vioolspelen, dat hij alleen tot zijn eigen genoegen doet, en de betuigingen van de redacteurs, dat het hunne gewoonte niet is datgene te doen, wat hij opmerkt dat zij juist in den geheelen stapel, dien hij voor zich heeft, onophoudelijk gedaan hebben.

Hij heeft ook zijn feestdagen. Het zal bij voorbeeld koppermaandag zijn: koppermaandag, een dag, waarop de boekdrukkersgezellen bij u in de stad de deuren afloopen met eene fatsoenlijke bedelarij; laatste beroep op eene mildheid die reeds achtervolgens in de begeerigheid van diender, koster, stovenzetter, lantarenopsteker, brandblusscher, brandbezorger, torenwachter, knecht van ’t Nut, en van wie niet al? heeft moeten voorzien. Wij kennen hier niemand in dat vak dan den boschwachter, die ons zijn groen almanakje komt aanbieden; en wien wij bij die gelegenheid de houtbrekers nog eens aanbevelen, want, om de waarheid te zeggen, deze, en de menigvuldige kraaien, zijn onze eenige winterrampen. – Maar ik wilde van koppermaandag spreken. Dan hebben wij bij voorbeeld hier de groote houtveiling, een publieke feestelijkheid, oneindig meer vermakelijk dan eene groote parade, indien gij mij gelooven wilt.”

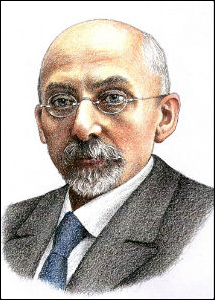

Nicolaas Beets (13 september 1814 – 13 maart 1903)

Het Hildebrand monument in Haarlem

De Oostenrijkse dichteres en schrijfster Marie Freifrau von Ebner-Eschenbach werd geboren op slot Zdislavice bij Kroměří¸ in Moravië op 13 september 1830. Zie ook alle tags voor Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach op dit blog.

Die Sekunde

Ich meß nach der Dauer das Leben,

Berechnet nach Jahren die Zeit,

Ich zähle nicht Tag und nicht Stunde,

Ich hab’ in einer Sekunde

Durchlebt die Ewigkeit.

Viel Jahre zogen vorüber

Und ließen die Seele mir leer,

Es blieb von keinem mir Kunde.

Die eine, die eine Sekunde,

Vergess’ ich nimmermehr.

Ein kleines Lied

Ein kleines Lied! Wie geht’s nur an,

Daß man so lieb es haben kann,

Was liegt darin? erzähle!

Es liegt darin ein wenig Klang,

Ein wenig Wohllaut und Gesang

Und eine ganze Seele.

Lebenszweck

Hilflos in die Welt gebannt,

Selbst ein Rätsel mir,

In dem schalen Unbestand,

Ach, was soll ich hier?

– Leiden, armes Menschenkind,

Jede Erdennot,

Ringen, armes Menschenkind,

Ringen um den Tod.

Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (13 september 1830 – 12 maart 1916)

De Tsjechische dichter Otokar Březina werd geboren op 13 september 1868 in Počátky, Bohemen. Zie ook alle tags voor Otokar Březina op dit blog.

Schmerz des Menschen

Mit suggerierter Ohnmacht hat uns verwundet ein feindlicher Dämon,

In den Augen der Sonne funkelte auf sein harter, böser Blick;

Den zitternden Händen entfiel das Werkzeug deines Werkes

Auf den Steinblock in deinen Brüchen sanken wir bange zurück.

Den Schweiß trockneten wir von den Stirnen, besprachen uns mit dem Tode,

Unter dem Himmel, der regungslos glühte, in der Erze ironischem Funkeln,

Und wie Kinder in den Schoß der Mutter ihr Haupt, legten wir

Unseren müden Gedanken in der Schöpfung ewige Trauer.

Und damals dank unserer eigenen magischen Macht, dem Geheimnis unseres Geschlechtes,

Dem Privilegium unseres verborgenen Adels, litten wir,

Gefangene Fürsten in den Goldwäschen des siegreichen Eroberers,

Bewacht von unsichtbaren Aufsehern,

Wenn sie gedenken ihrer Städte, aufgeblüht über den Seen,

Des Heimathimmels Sterne in mystischen Dämmerungen

Und in der Stille ihrer Hast der Glocken Chöre tausendstimmig,

Und des Jauchzens treuer Scharen bei Krönungsfesten …

Vertaald door Emil Saudek

Otokar Březina (13 september 1868 – 25 maart 1929)

De Poolse dichter Julian Tuwim werd geboren in Łódź op 13 september 1894. Zie ook alle tags voor Julian Tuwim op dit blog.

Switch

In the wall there sticks a little switch,

A little switch – electric, which –

Just give that little switch a click –

Brings you light double quick.

It’s easy all right:

Click and there’s light!

Flick once more – then

We’re in darkness again.

And if you give it another go,

You get the glow you had before.

It has such a secret might,

There in the wall, that tiny trick!

Night – light –

Light – night.

But tell me what’s that little switch?

A spark? A candle in a stick?

How’d it get there? From where can it be?

It’s no sparkle. It’s a cable.

Just a wire and – it’s electricity!!

Just flick the switch and – electricity!

Electrically slick electriciteeeee!

So where’s the light from?

Now you see!

Vertaald door David Malcolm

The ABCs

The ABCs fell off the mantelpiece,

Slammed against the ground,

They scattered into all four corners,

And shattered all around:

I—misplaced its dot,

H—is strangely squat,

B—bruised its belly,

A—‘s legs turned to jelly,

O—popped like a balloon,

causing P to swoon,

T—lost its hat,

L—jumped into U, just like that,

S—straightened out,

R—broken right leg no doubt,

W—is head-over-heels,

discovering exactly how M feels.

Vertaald door Pacze Moj

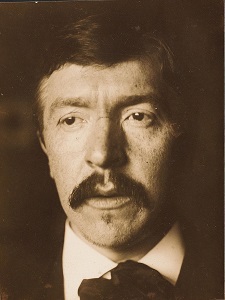

Julian Tuwim (13 september 1894 – 27 december 1953)

Hier met de Russische schrijver Ilya Erenburg (links)

De Nederlandse dichter, schrijver en taalkundige Muus Jacobse werd op 13 september 1909 als Klaas Hanzen Heeroma geboren op het waddeneiland Terschelling. Zie ook alle tags voor Muus Jacobse op dit blog.

1914

Toen de oorlog uitbrak, was ik nog klein.

Mijn vader zocht zijn oud soldatenpak

Van zolder uit een doos vlak onder ’t dak,

En wij brachten hem samen naar de trein.

En ik wist niet, waarvoor dat was. En toen

Vroeg ik het aan mijn moeder. En ik hoorde,

Dat nu de soldaten elkaar vermoordden.

Mijn vader ook? Die zou dat toch niet doen –

Nu ben ik groot en wijs en veel vergeten,

Van wat de dwazen en de kindren weten

En waar ik, als ik er aan denk, om lach.

Maar als wij, grote mensen, ’t niet verhindren,

Dat er weer oorlog komt, God, geef ons kindren,

Die nog begrijpen, dat het toch niet mag.

Het boek

Het Woord van het begin

Sluit alle woorden samen.

Zij zeggen ja en amen

En krijgen slot en zin.

God heeft zegen en vloek

Van de dood en het leven

Eens voor al opgeschreven.

God is een open boek.

En ik begrijp vaak niet,

Als ik zijn held’re geheimen

Moet navertellen in rijmen,

Wat Hij daar nog in ziet.

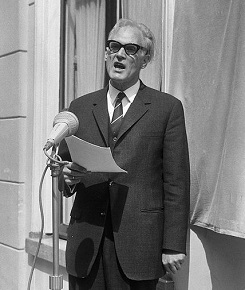

Muus Jacobse (13 september 1909 – 21 november 1972)

In 1966

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 13e september ook mijn twee blogs van 13 september 2015.