De Amerikaanse schrijver Jim Knipfel werd geboren op 2 juni 1965 in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Zie ook alle tags voor Jim Knipfel op dit blog.

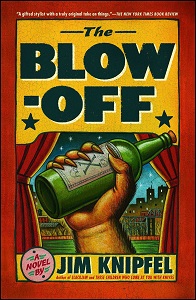

Uit: The Blow-off

“Why do you suppose they call that one the Black Hole?” Annie shouted into his ear in an effort to be heard over the tedious, thumping rhythms of the ride’s soundtrack—some insipid pop tune or another—blasting at jet engine levels. The “ride” itself appeared to be nothing more than a small wooden shack capable of holding no more than five or six people at a time, so long as none of those people moved. Yet there was a line of ticket holders twenty or thirty long, eagerly awaiting a chance to step inside. “You’d be surprised,” he shouted back. The Saturday night crowd was a swamp of hairy arms and soiled logo T-shirts, wailing children, haggard sundresses, droop-ing bellies, body odor, and cigar smoke. “What’s with you, you hit your head on something?” Annie asked once the noise had faded to tolerable levels. She’d noticed his face and it worried her. At first she thought he might be having a stroke. “What’s wrong?” “You’re smiling.” Hank stopped walking to assess what his face was up to, exam-ining it with his free hand. She was right. The smile dropped away. “Sorry,” he said. He looked around. “C’mon, let’s find a beer stand. Maybe that Chinaman who was here last year’s still around someplace.” She twisted the flesh of his upper arm again. She wasn’t fooling around. “Ow! Christ,” he yelped, yanking his arm away and rubbing the point of assault. “Why do you keep doing that?” “Don’t use that word in public.” Her whisper was fierce. “Take a look around you. You shouldn’t even use it at home.” “What word? That’s the fourth time tonight and I don’t even know what I’m saying.”

Despite the repeated attacks, Henry (“Hank”) Kalabander was in his element. It might have been his second or third element in terms of priorities, but it was without question one of the top five. He brought Annie to the Meadowlands Fair every year. Be-fore Annie, he’d brought his first wife. And before his first wife, he brought whoever was handy. Or he came alone. Annie had caught him smiling the first year he’d brought her here, too. It was the first time she’d seen him do that in public. “But you hate crowds,” she’d pointed out back then. “Yes . . . yes I do. But I live in New York.” “And you hate New York. So why do you like it here? It’s more crowded than Midtown, and you haven’t been to Midtown in sev-enteen years.” “I’m not so inflexible that there can’t be exceptions to the rule.” “Bullshit.” “Okay then, I’m not so inflexible that there can’t be this one single exception to the rule. More going on here than in goddamn Times Square.” “I might almost accept that,” she finally conceded. That was some seven or eight years back. He knew in his heart it wasn’t a real explanation, that nothing had been settled, and that he’d be back the following year and the year after that (as he had been ever since), trying to figure out the answer for himself. “Where’s that fuckin’ Chinaman?” He was swinging his head from side to side, peering through the crowds, the rides, the game booths with each futile pass in search of a beer shack. Annie refrained from pinching him this time, afraid she might do some real damage. “Hank, we talked about this a few months ago, remember? It was on the news. They don’t sell beer here any-more. Some kind of statute—like they did in the city with the street fairs.”

Jim Knipfel (Green Bay, 2 juni 1965)

De Duitse schrijver en literatuurcriticus Marcel Reich-Ranicki werd geboren op 2 juni 1920 in Włocławek, Polen. Zie ook alle tags voor Marcel Reich-Ranicki op dit blog.

Uit: Meine Geschichte der deutschen Literatur

„Und weil das Herz, wie man schon im Mittelalter zu wissen glaubte, eben verschließbar ist, kann es gewisse Schwierigkeiten und auch Möglichkeiten geben – nämlich mit dem Schlüssel. In einem der ältesten und schönsten deutschen Liebesgedichte, in jenem, das aus nur sechs Versen besteht und mit den Worten beginnt: »Du bist min, ich bin din: /Des solt du gewis sin«, ist die oder der Geliebte im Herzen verschlossen, zu dem es ein Schlüsselein gibt; aber es ist abhanden gekommen, und so muss sie oder er immer darin, im Herzen also, bleiben.

Es gibt kaum ein Substantiv, das die Menschen, jedenfalls in Europa, so häufig und in so vielen Verbindungen gebrauchen wie dieses eine: das Herz. Es gibt auch kaum ein Eigenschaftswort, das man nicht früher oder später mit der Vokabel »Herz« gekoppelt hätte. Ein Herz kann warm und weich sein, treu und traurig, klein und kalt, heiß und hart, gütig und großzügig, stolz und steinern. Kurz: Es kann alles sein. Groß ist auch die Zahl der deutschen Adjektive, die aus dem Wort »Herz« gebildet wurden. Wir sprechen von barmherzigen, engherzigen und hartherzigen, von herzlichen und herzhaften, von herzlosen und herzgläubigen Menschen.

Mehr noch: Das Herz, ein Körperteil, kann seinerseits, so wollen es manche Dichter, und nicht die schlechtesten, ebenfalls Körperteile haben, zumindest Knie. Jedenfalls schrieb Kleist am 24. Januar 1808 an Goethe, dem er das erste Heft des »Phoebus« zuschickte: »Es ist auf den ›Knien meines Herzens‹, daß ich damit vor Ihnen erscheine.« Allerdings hat Kleist die Wendung »Knien meines Herzens« mit Anführungszeichen versehen.

Woher stammen diese Worte? Wir wissen es nicht, doch wurde vermutet, er habe jenen Autor zitiert, den die Schriftsteller am liebsten zitieren – nämlich sich selbst. Denn in seiner »Penthesilea« heißt es: »O du, /Vor der mein Herz auf Knien niederfällt …« Es kann aber auch sein, dass Kleist – fleißige Germanisten haben es nachgewiesen – artigerweise seinen Adressaten zitiert hat, dem diese Wendung schon in frühen Jahren unterlaufen ist. Nur hat auch Goethe die »Knie des Herzens« keineswegs erfunden, es gab sie schon bei Petrarca. Und auch dieser hat sie entliehen, nämlich aus der Bibel.“

Marcel Reich-Ranicki (2 juni 1920 – 18 september 2013)

Włocławek, Polen

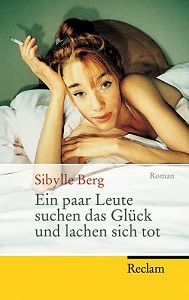

De Duitse schrijfster Sibylle Berg werd geboren in Weimar op 2 juni 1962. Zie ook alle tags voor Sibylle Berg op dit blog.

Uit: Ein paar Leute suchen das Glück und lachen sich tot (Tom geht weg)

„Vera und Helge sind verheiratet. Schon lange. Wissen sie eigentlich gar nicht, warum. Sie sitzen draußen, auf dem Balkon. Es ist ein Sommerabend. Die Luft fleischwarm und macht im Menschen das Gefühl, daß er etwas unternehmen müßte, in dieser Nacht, das ihr gerecht wird, in der Aufregung, die sie verursacht. Was kann ich machen, mit so einer schönen Nacht, denkt sich Vera und weiß keine Antwort. Und eigentlich auch keine Frage. So eine Nacht ist eben eine Nacht. Die will gar nichts gemacht kriegen. Vera sieht Helge an. Der sitzt neben ihr und ist tausend Gedanken entfernt. Sie würde gerne rübergehen, zu ihm. Aber sie weiß nicht wie. Sie schaut in den Himmel und sucht dort den Satz. Der alles ändert. Ein Satz nur. Himmel, schenk mir einen. Der Himmel bleibt stumm und schön, und Wunder gibt es eben nicht. Wunder muß es aber geben, denkt Vera und guckt stur in den Himmel. Und dann guckt sie zu Helge rüber und der guckt geradeaus. Helge trinkt Bier. »Helge …« Helge trinkt Bier. »Ein schöner Abend.« Helge bleibt stumm, und Vera könnte gut tot umfallen. So leer fühlt sie sich an und weiß gar nicht, warum sie noch hier sitzen soll, oder aufstehen, oder weiterleben. Der Himmel ist ein Verräter, und einen Gott gibt es nicht. Vera nimmt ihre Hand und legt sie auf die von Helge. Da liegt sie dann so. Helges Hand bewegt sich nicht. Sie fühlt, daß ihre Hand weglaufen möchte. Sie mag das schwitzige Ding nicht anfassen müssen. Nichts ist peinlicher als eine Hand, die man anfaßt und die sich nicht bewegt, denkt Veras Hand, sondern nur atmet. Vor lauter Widerwillen laut atmet. Das denkt sich Veras Hand so, und Vera selbst schämt sich und nimmt ihre Hand weg, um sich eine Strähne aus dem Gesicht zu wischen. Sie steht auf und geht in die Küche. Der Abwasch steht noch da. Vera bindet sich die Schürze um. Sie wäscht ab und überlegt sich, was sie morgen ins Büro anziehen soll. Dann fällt ihr ein, daß Nora bald Geburtstag hat, und sie schüttelt den Kopf. Es gibt doch wirklich wichtigere Sachen als so einen blöden, warmen Abend und eine Hand, die nicht von ihr angefaßt werden will.“

Sibylle Berg (Weimar, 2 juni 1962)

Cover

De Canadese schrijfster Carol Shields werd op 2 juni 1935 in Oak Park, Chicago, geboren als Carol Warner. Zie ook alle tags voor Carol Shields op dit blog.

Uit: The Stone Diaries

“Only bread seems to ease her malaise, buttered bread, enormous slabs of it, what she’s heard people in this village refer to as doorsteps. She eats it fresh from the oven, slice after slice, sometimes not bothering with the knife, just tearing it off in handfuls. One day, alone in this kitchen, she consumed an entire loaf between noon and supper. (one of the loaves burned, she explained to her husband, anxious to account for the missing bread—as though a man of my father’s dreamy disposition would notice so small an item, as though any man would notice such a thing.) Frequently she sprinkles sugar on top of the buttered bread. The surface winks with brilliance, its crystals working between her teeth, giving her strength. She imagines the soft dough entering the bin of her stomach, lining that bitter bloated vessel with a cottony warmth that absorbs and neutralizes the poisons of her own body. Her inability to feel love has poisoned her, swallowed down along with the abasement of sugar, yeast, lard, and flour; she knows this for a fact. She tries, she pretends pleasure, as women are encouraged to do, but her efforts are punished by a hunger that attacks her when she’s alone, as she is on this hot July day, hidden away in a dusty, landlocked Manitoba village (half a dozen unpaved streets, a store, a hotel, a Methodist Church, the Canadian Pacific Railway Station, and a boarding house on the corner of Bishop Road for the unmarried men). She seems always to be waiting for something fresh to happen, but her view of this “something” is obscured by ignorance and the puffiness of her bodily tissue. At night, embarrassed, she gathers her nightdress close around her. She never knows when she blows out the lamp what to expect or what to make of her husband’s cries, which are, thankfully, muffled by the walls of the wood-framed company house where she and my father live. Two rooms up, two down, a privy out back. She knows only that she stands apart from any coherent history, separated from the ordinary consolation of blood ties, and covered over and over again these last two years by Cuyler Goodwill’s immense, unfathomable ardor. Niagara in all its force is what she’s reminded of as he climbs on top of her each evening, a thundering let loose against the folded interior walls of her body. It’s then she feels most profoundly buried, as though she, Mercy Goodwill, is no more than a beating of blood inside the vault of her flesh, her wide face, her thick doughy neck, her great loose breasts and solid boulder of a stomach. Standing in her back kitchen, my mother’s thighs, like soft white meat (veal or chicken or fatty pork come to mind) rub together under her cotton drawers—which are wet, she suddenly realizes, soaked through and through. There are double and triple ruffles of fat around her ankles and wrists, and these ridged extremities are slick with perspiration. Her large swollen fingers press into the boards of the kitchen table, and her left hand, her wedding ring buried there in soft flesh, is throbbing with poison.”

Carol Shields (2 juni 1935 – 16 juli 2003)

Cover

De Nederlandse sportjournalist en schrijver Jean Nelissen werd geboren in Geleen op 2 juni 1936. Zie ook alle tags voor Jean Nelissen op dit blog.

Uit: De Bijbel van 100 jaar Tour

“Ik heb Joop gevraagd of hij met mij wil rijden. ‘Ik kom: belooft hij. De gentlemankoers is een heuse happening. een manie van topsporters. de mediawereld en de coureurs Martijn Lindenberg en ik besluiten om een dag eerder naar Hummelo af te reizen. Dan zijn we tenminste op tijd en fit voor de race. We huren een kamer in De Gouden Karper. En besluiten ėen afzakkertje te nemen en dan vroeg te gaan slapen- En dan geschiedt het ongeluk: we komen Wim Oorlog tegen. directeur van Vredestein en sponsor van de yentlemankoers ‘Ha. de mannen, kom ik schenk een borrel!’ Hij gaat ons voor en giet pure whisky in limonadeglazen van Hero Het wordt laat en ik heb het idee dat ik pas een halfuur in bed lig als Joop op de deur bonst. Hij is om drie uur in de nacht uit Parijs vertrokken en roept ‘Opstaan. warmrijden” Ik kom half overeind en roep ‘Die vervloekte Oorlog.’ Joop haalt zwarte koffie In het restaurant. Ik neem een koude douche en trek mijn koerskleding aan. Joop vraagt. ‘Hoe gaan we rijden?”’

Jean Nelissen (2 juni 1936 – 1 september 2010)

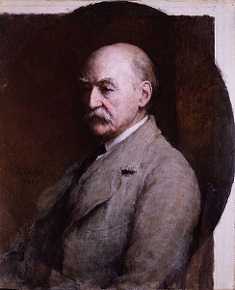

De Engels romanschrijver en dichter Thomas Hardy werd op 2 juni 1840 geboren in Higher Bockhampton, bij Dorchester. Zie ook alle tags voor Thomas Hardy op dit blog.

Uit: Far from the Madding Crowd

“What possessed her to indulge in such a performance in the sight of the sparrows, blackbirds, and unperceived farmer who were alone its spectators,–whether the smile began as a factitious one, to test her capacity in that art,–nobody knows; it ended certainly in a real smile. She blushed at herself, and seeing her reflection blush, blushed the more.

The change from the customary spot and necessary occasion of such an act–from the dressing hour in a bedroom to a time of travelling out of doors–lent to the idle deed a novelty it did not intrinsically possess. The picture was a delicate one. Woman’s prescriptive infirmity had stalked into the sunlight, which had clothed it in the freshness of an originality. A cynical inference was irresistible by Gabriel Oak as he regarded the scene, generous though he fain would have been. There was no necessity whatever for her looking in the glass. She did not adjust her hat, or pat her hair, or press a dimple into shape, or do one thing to signify that any such intention had been her motive in taking up the glass. She simply observed herself as a fair product of Nature in the feminine kind, her thoughts seeming to glide into far-off though likely dramas in which men would play a part–vistas of probable triumphs–the smiles being of a phase suggesting that hearts were imagined as lost and won. Still, this was but conjecture, and the whole series of actions was so idly put forth as to make it rash to assert that intention had any part in them at all.

The waggoner’s steps were heard returning. She put the glass in the paper, and the whole again into its place.

When the waggon had passed on, Gabriel withdrew from his point of espial, and descending into the road, followed the vehicle to the turnpike-gate some way beyond the bottom of the hill, where the object of his contemplation now halted for the payment of toll. About twenty steps still remained between him and the gate, when he heard a dispute. It was a difference concerning twopence between the persons with the waggon and the man at the toll-bar.

“Mis’ess’s niece is upon the top of the things, and she says that’s enough that I’ve offered ye, you great miser, and she won’t pay any more.” These were the waggoner’s words.

“Very well; then mis’ess’s niece can’t pass,” said the turnpike-keeper, closing the gate.

Oak looked from one to the other of the disputants, and fell into a reverie. There was something in the tone of twopence remarkably insignificant. Threepence had a definite value as money–it was an appreciable infringement on a day’s wages, and, as such, a higgling matter; but twopence–“Here,” he said, stepping forward and handing twopence to the gatekeeper; “let the young woman pass.” He looked up at her then; she heard his words, and looked down.”

Thomas Hardy (2 juni 1840 – 11 januari 1928)

Cover

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 2e juni ook mijn blog van 2 juni 2018 deel 2.