De Nederlandse schrijver en dichter Simon Carmiggelt werd geboren op 7 oktober 1913 in Den Haag. Zie ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2006 en mijn blog van 7 oktober 2007 en ook mijn blog van 7 maart 2008 en ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2009.

Uit: Brieven aan Gerard Reve

„20 mei 1971

Beste Gerard,

Deze brief, die antwoordt op de jouwe van 16 mei, begin ik met een visuele herinnering. Ik weet niet meer hoeveel jaar geleden. Maar je was pas tot het bewustzijn gekomen van je homofilie en er open voor uitgekomen in een publicatie.

Ik zat op een zomermiddag op een caféterras op het Kleine Gartmanplantsoen. Jij liep langs, met iemand. Je zag me niet. Je ging voor het Citytheater in de rij staan, naar ik meen om een film van Fellini te gaan zien. Ik keek naar je en dacht: ‘Zijn motoriek is veranderd. Hij loopt en staat anders. Onbevangener, bevrijd.’ En je praatte met de persoon die je bij je had op een vrolijke manier, geheel ontspannen. Ik dacht: ‘Hij is gelukkig, geloof ik. Wat fijn voor hem. En wat een ramp voor hem als schrijver en voor mij als lezer.’

Dit is geen ‘anecdote’, maar wat mij betreft pure ernst. En misschien een bijdrage tot het probleem van je depressies. Iedere schrijver krijgt de depressies die hij verdient. Jij krijgt ze op jouw formaat. Maar als ze je niet verhinderen ‘Gezond leven’ te schrijven, vormen ze, naar mijn mening, geen probleem van betekenis. Wel voor jou als ‘particulier’ natuurlijk en voor je omgeving. Maar niet voor jou als schrijver en voor mij als lezer. Ik ben niet bezig je ergens van te overtuigen. Dat is natuurlijk onmogelijk. Maar ik betoog alleen, als lezer, dat je wanhoop en je vertwijfeling volstrekt onmisbaar zijn voor je werk. Als je, geheel bij wijze van spreken, een – uiteraard niet alcoholische – toverdrank innam, die je wensloos gelukkig maakt, zou je als schrijver sterven. Het valt te betwijfelen of je dan nog schrijven zou. Waarom? Gelukkige mensen hoeven dat niet. Maar als je het wel zou doen, wil ik het niet lezen. Wat heb ik aan de onbeduidende mededelingen van een gelukkig mens? Jouw hele werk drijft, tot zinken bereid, op de donkere onderstroom van je wanhoop. Haal je die eronderuit, dan blijft er niets over. Vandaar mijn vrees, toen ik je zag staan voor het Citytheater. Ik bedoel: onderwaardeer je wanhoop niet. Als je niet meer wanhoopt en je ‘happy’ voelt, zal je stijl de spankracht verliezen, die deze stijl nu bezit. ‘Particulier’ is het wel vervelend voor je – toegegeven. Maar wat betekent de particulariteit van een schrijver? Niets. Lezers zijn wreed. En Hemingway had gelijk, toen hij zei: ‘Een schrijver kan niet met pensioen gaan’ en zich door zijn kop schoot toen hij dat laatste boek over Parijs niet uit zijn pen kon krijgen. Het is modieus het een rotboek te vinden. Dat is het niet, maar het staat beneden zijn peil. Maar als jij nu ‘Gezond leven’ kunt schrijven, moet je de zelfmoord echt nog wel even uitstellen. Begrijp me wel: ik wil je niet, als ‘humanist’, tegen beter weten in leven houden. Ik praat als egoïstische lezer, die alles nog niet gehad heeft.

Maar die het wel allemaal hebben wil. Als jij voortijdig uitknijpt, besteel je me. Dat is een misdrijf. Zie de arresten van de Hoge Raad.

Simon Carmiggelt (7 oktober 1913 – 30 november 1987)

Carmiggelt met zijn vrouw Tini, brons van Wim Kuijl in Rheden

De Amerikaanse dichter en schrijver James Whitcomb Riley werd geboren op 7 oktober 1849 in Greenfield, Indiana. Zie ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2006 en ook mijn blog van 7 maart 2008 en ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2009.

Dead Leaves

Dawn

As though a gipsy maiden with dim look,

Sat crooning by the roadside of the year,

So, Autumn, in thy strangeness, thou art here

To read dark fortunes for us from the book

Of fate; thou flingest in the crinkled brook

The trembling maple’s gold, and frosty-clear

Thy mocking laughter thrills the atmosphere,

And drifting on its current calls the rook

To other lands. As one who wades, alone,

Deep in the dusk, and hears the minor talk

Of distant melody, and finds the tone,

In some wierd way compelling him to stalk

The paths of childhood over,–so I moan,

And like a troubled sleeper, groping, walk.

Dusk

The frightened herds of clouds across the sky

Trample the sunshine down, and chase the day

Into the dusky forest-lands of gray

And somber twilight. Far, and faint, and high

The wild goose trails his harrow, with a cry

Sad as the wail of some poor castaway

Who sees a vessel drifting far astray

Of his last hope, and lays him down to die.

The children, riotous from school, grow bold

And quarrel with the wind, whose angry gust

Plucks off the summer hat, and flaps the fold

Of many a crimson cloak, and twirls the dust

In spiral shapes grotesque, and dims the gold

Of gleaming tresses with the blur of rust.

Night

Funereal Darkness, drear and desolate,

Muffles the world. The moaning of the wind

Is piteous with sobs of saddest kind;

And laughter is a phantom at the gate

Of memory. The long-neglected grate

Within sprouts into flame and lights the mind

With hopes and wishes long ago refined

To ashes,–long departed friends await

Our words of welcome: and our lips are dumb

And powerless to greet the ones that press

Old kisses there. The baby beats its drum,

And fancy marches to the dear caress

Of mother-arms, and all the gleeful hum

Of home intrudes upon our loneliness.

James Whitcomb Riley (7 oktober 1849 – 22 juli 1916)

Buste van Riley in Indianapolis

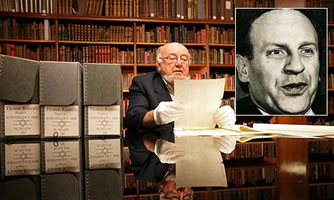

De Australische schrijver Thomas Keneally werd geboren op 7 oktober 1935 in Sydney. Zie ook mijn blog van 7 maart 2008 en ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2009.

Uit: Schindler’s List

„The family Schindler was Catholic. So too was the family of young Amon Goeth, by this time also completing the Science Course and sitting for the Matura examinations in Vienna.

Oskar’s mother, Louisa, practiced her faith with energy, her clothes redolent all Sunday of the incense burned in clouds at High Mass in the Church of St. Maurice. Hans Schindler was the sort of husband who drives a woman to religion. He liked cognac; he liked coffeehouses. A redolence of brandy-warm breath, good tobacco, and confirmed earthiness came from the direction of that good monarchist, Mr. Hans Schindler.

The family lived in a modern villa, set in its own gardens, across the city from the industrial section. There were two children, Oskar and his sister, Elfriede. But there are not witnesses left to the dynamics of that household, except in the most general terms. We know, for example, that it distressed Frau Schindler that her son, like his father, was a negligent Catholic.

But it cannot have been too bitter a household. From the little that Oskar would say of his childhood, there was no darkness there. Sunlight shines among the fir trees in the garden. There are ripe plums in the corner of those early summers. If he spends a part of some June morning at Mass, he does not bring back to the villa much of a sense of sin. He runs his father’s car out into the sun in front of the garage and begins tinkering inside its motor. Or else he sits on a side step of the house, filing away at the carburetor of the motorcycle he is building.

Oskar had a few middle-class Jewish friends, whose parents also sent them to the German grammar school. These children were not village Ashkenazim—quirky, Yiddish-speaking, Orthodox—but multilingual and not-so-ritual sons of Jewish businessmen. Across the Hana Plain and in the Beskidy Hills, Sigmund Freud had been born of just such a Jewish family, and that not so long before Hans Schindler himself was born to solid German stock in Zwittau.

Oskar’s later history seems to call out for some set piece in his childhood. The young Oskar should defend some bullied Jewish boy on the way home from school. It is a safe bet it didn’t happen, and we are happier not knowing, since the event would seem too pat. Besides, one Jewish child saved from a bloody nose proves nothing. For Himmler himself would complain, in a speech to one of his Einsatzgruppen, that every German had a Jewish friend. ” ‘The Jewish people are’going to be annihilated,’ says every Party member. ‘Sure, it’s in our program: elimination of the Jews, annihilation—we’ll take care of it.’ And then they all come trudging, eighty million worthy Germans, and each one has his one decent Jew. Sure, the others are swine, but this one is an A-One Jew.”

Thomas Keneally (Sydney, 7 oktober 1935)

Inzet Oskar Schindler

De Nederlandse schrijfster en beeldend kunstenares Dirkje Kuik werd geboren in Utrecht op 7 oktober 1929. Zie ook mijn blog van 7 maart 2008 en ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2009.

Het museum Jo, weet je nog

Het museum Jo, weet je nog,

kleine vriendelijke doffer, wie weet.

Alle schilderkunst sloegen we

over, behalve Sinte Caecilia

en de graflegging, ons heer

in zijn glazen kastje, schilder

de mensen van pintor Scorel zegt men.

Zeer beschadigd waren we, dronken

van vroeger en wijn, venijn van de kunst,

een gunst zo maar gegeven, drie gulden,

aangeschoten doffer weet je nog, de toegang.

Metamorfose

Vandaag ben ik een lekkker dier,

eenhoorn, hoewel ten halve stier, een fabel.

Morgen wellicht Jan zonder land

Och arme kruidenier,

de kat met negen staarten.

Het boegbeeld van een schip, gestrand,

een zeemeermin gebleven na de vloed,

Krake, de leden in het vissersnet, verlaten,

Kleio, de neus in het zand.

Dirkje Kuik (7 oktober 1929 – 18 maart 2008)

Zelfportret, 1955

De Canadese schrijver, archeoloog, antropoloog Steven Erikson (pseudoniem van Steve Rune Lundin) werd geboren in Toronto op 7 oktober 1959. Zie ook mijn blog van 7 maart 2008 en ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2009.

Uit: Memories Of Ice

„Swallows darted through the clouds of midges dancing over the mudflats. The sky above the marsh remained grey, but it had lost its mercurial wintry gleam, and the warm wind sighing through the air above the ravaged land held the scent of healing.

What had once been the inland freshwater sea the Imass called Jaghra Til – born from the shattering of the Jaghut ice-fields – was now in its own death-throes. The pallid overcast was reflected in dwindling pools and stretches of knee-deep water for as far south as the eye could scan, but none the less, newly birthed land dominated the vista.

The breaking of the sorcery that had raised the glacial age returned to the region the old, natural seasons, but the memories of mountain-high ice lingered. The exposed bedrock to the north was gouged and scraped, its basins filled with boulders. The heavy silts that had been the floor of the inland sea still bubbled with escaping gases, as the land, freed of the enormous weight with the glaciers’ passing eight years past, continued its slow ascent.

Jaghra Til’s life had been short, yet the silts that had settled on its bottom were thick. And treacherous.

Pran Chole, Bonecaster of Cannig Tol’s clan among the Kron Imass, sat motionless atop a mostly buried boulder along an ancient beach ridge. The descent before him was snarled in low, wiry grasses and withered driftwood. Twelve paces beyond, the land dropped slightly, then stretched out into a broad basin of mud.

Three ranag had become trapped in a boggy sinkhole twenty paces into the basin. A bull male, his mate and their calf, ranged in a pathetic defensive circle. Mired and vulnerable, they must have seemed easy kills for the pack of ay that found them.

But the land was treacherous indeed. The large tundra wolves had succumbed to the same fate as the ranag. Pran Chole counted six ay, including a yearling. Tracks indicated that another yearling had circled the sinkhole dozens of times before wandering westward, doomed no doubt to die in solitude.

How long ago had this drama occurred? There was no way to tell. The mud had hardened on ranag and ay alike, forming cloaks of clay latticed with cracks. Spots of bright green showed where windborn seeds had germinated, and the Bonecaster was reminded of his visions when spiritwalking – a host of mundane details twisted into something unreal. For the beasts, the struggle had become eternal, hunter and hunted locked together for all time.“

Steven Erikson (Toronto, 7 oktober 1959)

De Duitse, romantische dichter Wilhelm Müller werd geboren op 7 oktober 1794 in Dessau. Zie ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2006 en ook mijn blog van 7 maart 2008 en ook mijn blog van 7 oktober 2009.

Der Müller und der Bach

[Der Müller]

Wo ein treues Herze

In Liebe vergeht,

Da welken die Lilien

Auf jedem Beet.

Da muß in die Wolken

Der Vollmond gehn,

Damit seine Tränen

Die Menschen nicht sehn.

Da halten die Englein

Die Augen sich zu,

Und schluchzen und singen

Die Seele zu Ruh

[Der Bach]

Und wenn sich die Liebe

Dem Schmerz entringt,

Ein Sternlein, ein neues,

Am Himmel erblinkt.

Da springen drei Rosen,

Halb rot, halb weiß,

Die welken nicht wieder,

Aus Dornenreis.

Und die Engelein schneiden

Die Flügel sich ab,

Und gehn alle Morgen

Zur Erde hinab.

[Der Müller]

Ach, Bächlein, liebes Bächlein,

Du meinst es so gut:

Ach, Bächlein, aber weißt du,

Wie Liebe tut?

Ach, unten, da unten,

Die kühle Ruh!

Ach, Bächlein, liebes Bächlein,

So singe nur zu.

Wilhelm Müller (7 oktober 1794 – 1 oktober 1827)

Mogelijke schilders: Johann Heinrich Beck of Franz Krüger