De Amerikaanse dichteres en schrijfster Sylvia Plath werd geboren op 27 oktober 1932 in Jamaica Plain, een buitenwijk van Boston. Zie ook alle tags voor Sylvia Plath op dit blog.

Circus in Three Rings

In the circus tent of a hurricane

designed by a drunken god

my extravagant heart blows up again

in a rampage of champagne-colored rain

and the fragments whir like a weather vane

while the angels all applaud.

Daring as death and debonair

I invade my lion’s den;

a rose of jeopardy flames in my hair

yet I flourish my whip with a fatal flair

defending my perilous wounds with a chair

while the gnawings of love begin.

Mocking as Mephistopheles,

eclipsed by magician’s disguise,

my demon of doom tilts on a trapeze,

winged rabbits revolving about his knees,

only to vanish with devilish ease

in a smoke that sears my eyes.

Channel Crossing

On storm-struck deck, wind sirens caterwaul;

With each tilt, shock and shudder, our blunt ship

Cleaves forward into fury; dark as anger,

Waves wallop, assaulting the stubborn hull.

Flayed by spray, we take the challenge up,

Grip the rail, squint ahead, and wonder how much longer

Such force can last; but beyond, the neutral view

Shows, rank on rank, the hungry seas advancing.

Below, rocked havoc-sick, voyagers lie

Retching in bright orange basins; a refugee

Sprawls, hunched in black, among baggage, wincing

Under the strict mask of his agony.

Far from the sweet stench of that perilous air

In which our comrades are betrayed, we freeze

And marvel at the smashing nonchalance

Of nature : what better way to test taut fiber

Than against this onslaught, these casual blasts of ice

That wrestle with us like angels; the mere chance

Of making harbor through this racketing flux

Taunts us to valor. Blue sailors sang that our journey

Would be full of sun, white gulls, and water drenched

With radiance, peacock-colored; instead, bleak rocks

Jutted early to mark our going, while sky

Curded over with clouds and chalk cliffs blanched

In sullen light of the inauspicious day.

Now, free, by hazard’s quirk, from the common ill

Knocking our brothers down, we strike a stance

Most mock-heroic, to cloak our waking awe

At this rare rumpus which no man can control :

Meek and proud both fall; stark violence

Lays all walls waste; private estates are torn,

Ransacked in the public eye. We forsake

Our lone luck now, compelled by bond, by blood,

To keep some unsaid pact; perhaps concern

Is helpless here, quite extra, yet we must make

The gesture, bend and hold the prone man’s head.

And so we sail toward cities, streets and homes

Of other men, where statues celebrate

Brave acts played out in peace, in war; all dangers

End : green shores appear; we assume our names,

Our luggage, as docks halt our brief epic; no debt

Survives arrival; we walk the plank with strangers.

Sylvia Plath (27 oktober 1932 – 11 februari 1963)

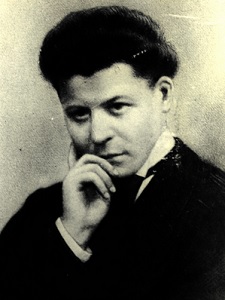

De Engelse dichter Dylan Thomas werd geboren op 27 oktober 1914 in Swansea in Wales. Zie ook alle tags voor Dylan Thomas op dit blog.

How Shall My Animal

How shall my animal

Whose wizard shape I trace in the cavernous skull,

Vessel of abscesses and exultation’s shell,

Endure burial under the spelling wall,

The invoked, shrouding veil at the cap of the face,

Who should be furious,

Drunk as a vineyard snail, flailed like an octopus,

Roaring, crawling, quarrel

With the outside weathers,

The natural circle of the discovered skies

Draw down to its weird eyes?

How shall it magnetize,

Towards the studded male in a bent, midnight blaze

That melts the lionhead’s heel and horseshoe of the heart

A brute land in the cool top of the country days

To trot with a loud mate the haybeds of a mile,

Love and labour and kill

In quick, sweet, cruel light till the locked ground sprout

The black, burst sea rejoice,

The bowels turn turtle,

Claw of the crabbed veins squeeze from each red particle

The parched and raging voice?

Fishermen of mermen

Creep and harp on the tide, sinking their charmed, bent pin

With bridebait of gold bread, I with a living skein,

Tongue and ear in the thread, angle the temple-bound

Curl-locked and animal cavepools of spells and bone,

Trace out a tentacle,

Nailed with an open eye, in the bowl of wounds and weed

To clasp my fury on ground

And clap its great blood down;

Never shall beast be born to atlas the few seas

Or poise the day on a horn.

Sigh long, clay cold, lie shorn,

Cast high, stunned on gilled stone; sly scissors ground in frost

Clack through the thicket of strength, love hewn in pillars drops

With carved bird, saint, and suns the wrackspiked maiden mouth

Lops, as a bush plumed with flames, the rant of the fierce eye,

Clips short the gesture of breath.

Die in red feathers when the flying heaven’s cut,

And roll with the knocked earth:

Lie dry, rest robbed, my beast.

You have kicked from a dark den, leaped up the whinnying light,

And dug your grave in my breast.

Dylan Thomas (27 oktober 1914 – 9 november 1953)

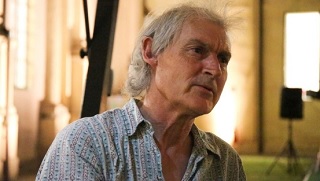

Tim Hollander als Dylan Thomas in de televisiefilm “A Poet in New York” uit 2014

De Nederlandse schrijfster Steffie van den Oord werd geboren op 27 oktober 1970, in Ammerzoden, Gelderland. Zie ook alle tags voor Steffie van den Oord op dit blog.

Uit: Vonk, een noodlottige liefde

“Het was een prachtige dag voor een executie, en toch voelde Andries van Anhout niet de voldoening die zich meestal aandiende als hij op het punt stond het schepengericht te dienen. Als jongen was hij al gewend zijn vader op het schavot te assisteren, maar zojuist, toen hij haar kinderen had opgemerkt, kon hij, scherprechter op leeftijd, maar één ding doen, in een niet bij zijn ambt passende opwelling: grijpen naar zijn zwarte lap, voortijdig, zodat ze haar niet zouden herkennen en de illusie konden koesteren dat hier een andere vrouw stond, niet hun moeder. Ook had hij het gedaan voor haar. Vonk, zo was hij haar kortweg gaan noemen.

De stilte die altijd kwam maar die nu volkomen leek, was met het blinddoeken ingetreden. Een zuigeling krijste: een stem die scherper was dan zijn gewette zwaard. ‘Mama…!’: hij hoorde het opnieuw. Kon dan niemand haar kinderen weghalen, ontsnapten ze nu al aan hun voorlopige voogd? Als ze die hadden. Zo kon hij zijn werk niet doen. Hij vloekte onhoorbaar, alweer onprofessioneel, hij keek naar de heren schepenen die – nogal ongebruikelijk – met elkaar in discussie waren gegaan. Hij wachtte op een teken dat hij verder kon, of niet; al zou dat raar zijn, zelden vertoond.

De hele stad wachtte. Langer dan anders wachtte hij. De eerste zonnige dag was het, de laatste dinsdag van maart, 1713 alweer.

Andries van Anhout had zijn eerste lijfstraf, twee harige rechtervingers, al dertig jaar achter zich – in één slag – ; talloze keren had hij in deze stad en elders de doodstraf voltrokken, met het zwaard, met het koord; zelden tot nooit had hij zich ergens iets van aangetrokken, vakkundig roofde hij vet op misdadige lijken voor zijn heilzame smeersels; maar deze vrouw, Vonk, om wie een moord was gepleegd – en terecht! dacht hij in een opwelling –, deze vrouw beroerde hem. En dat mocht niet. Het kon niet: ze beroerde hem. Niet eens omdat ze rossig was en met duizend sproeten bedekt en zelfs halfnaakt toch waardig, nee, dat was het niet; het was omdat ze anders was dan wie ook met wie hij te maken kreeg.

In haar diepste nood had hij haar gezien en misschien wel beter gekend dan haar man ooit, misschien zelfs beter dan haar minnaar: ook haar geest werd opgelicht door iets mysterieus, een inwendig soort sproeten, iets dat hij nog niet eerder was tegengekomen en waarover hij in het boek dat sinds generaties in de familie was, bondig alle geheimen bevattend, een losse aantekening had gemaakt: Standvastig, doch niet van godsvr. of devote aard. Op een los blad. Niet bedoeld om te bewaren voor toekomstige generaties scherprechters, laat staan voor zijn zoon, die stevig optrad met de stok.”

Steffie van den Oord (Ammerzoden, 27 oktober 1970)

De Engelse schrijfster Zadie Smith werd geboren op 27 oktober 1975 in Londen. Zie ook alle tags voor Zadie Smith op dit blog.

Uit: Feel Free

“Last time I was in Willesden Green I took my daughter to visit my mother. The sun was out. We wandered down Brondesbury Park toward the high road. The “French Market” was on, which is a slightly improbable market of French things sold in the concrete space between the pretty turreted remnants of Willesden Library (1894) and the brutal red-brick beached cruise ship known as Willesden Green Library Centre (1989), a substantial local landmark that racks up nearly five hundred thousand visits a year. We walked in the sun down the urban street to the concrete space—to market. This wasn’t like walking a shady country lane in a quaint market town ending up in a perfectly preserved eighteenth-century square. It was not even like going to one of these farmers’ markets that have sprung up all over London at the crossroads where personal wealth meets a strong interest in artisanal cheeses. But it was still very nice. Willesden French Market sells cheap bags. It sells CDs of old-time jazz and rock and roll. It sells umbrellas and artificial flowers. It sells ornaments and knickknacks and doodahs, which are not always obviously French in theme or nature. It sells water pistols. It sells French breads and pastries for not much more than you’d pay for the baked goods in Greggs down Kilburn High Road. It sells cheese, but of the decently priced and easily recognizable kind—Brie, goat’s, blue—as if the market has traveled unchanged across the Channel from some run-down urban suburb of Paris. Which it may have done for all I know. The key thing about Willesden’s French Market is that it accentuates and celebrates this concrete space in front of Willesden Green Library Centre, which is at all times a meeting place, though never quite so much as it is on market day. Everybody’s just standing around, talking, buying or not buying cheese, as the mood takes diem. It’s really pleasant. You could almost forget Willesden High Road was ten yards away. This matters. When you’re standing in the market you’re not going to work, you’re not going to school, you’re not waiting for a bus. You’re not heading for the Tube or shopping for necessities. You’re not on the high road where all these activities take place. You’re just a little bit off it, hanging out, in an open-air urban area, which is what these urban high streets have specifically evolved to stop people from doing. Everybody knows that if people hang around for any length of time in an urban area without purpose they are likely to become “antisocial.” And indeed there were four homeless drunks sitting on one of the library’s strange architectural protrusions, drinking Special Brew. Perhaps in a village they would be sitting under a tree, or have already been driven from the area by a farmer with a pitchfork. I do not claim to know what happens in villages. But here in Willesden they were sitting on their ledge and the rest of us were congregating for no useful purpose in the unlovely concrete space, simply standing around in the sunshine, like some kind of community.”

Zadie Smith (Londen, 27 oktober 1975)

De Egyptische schrijfster, gynaecologe, moslimfeministe en politiek activiste Nawal el Saadawi werd geboren in Kafr Tahla op 27 oktober 1931. Zie ook alle tags voor Nawal el Saadawi op dit blog.

Uit: Women At Point Zero (Vertaald door Sherif Hetata)

“Without looking me in the face, he said, ‘What do you mean, you can’t carry on like this? `I cannot continue to live in your house,’ I stammered. ‘I’m a woman, and you’re a man, and people are talking. Besides, you promised I’d stay only until you found me a job.’ He retorted angrily, ‘What can I do, get the heavens to intervene for you?’ `You’re busy all day in the coffee-house, and you haven’t even tried to find me a job. I’m going out now to look for one.’ I was speaking in low tones, and my eyes were fixed on the ground, but he jumped up and slapped me on the face, saying, ‘How dare you raise your voice when you’re speaking to me, you street walker, you low woman?’

His hand was big and strong, and it was the heaviest slap I had ever received on my face. My head swayed first to one side, then to the other. The walls and the floor seemed to shift violently. I held my head in my hands until they grew still again, then I looked upwards and our eyes met. It was as though I was seeing the eyes that now confronted me for the first time. Two jet black surfaces that stared into my eyes, travelled with an infinitely slow movement over my face, and my neck, and then dropped downwards gradually over my breast, and my belly, to settle somewhere just below it, between my thighs. A cold shiver, like the shiver of death, went through my body, and my hands dropped instinctively to cover the part on which his gaze was fixed, but his big strong hands moved quickly to jerk them away. The next moment he hit me with his fist in the belly so hard that I lost consciousness immediately. He took to locking me in the flat before going out. I now slept on the floor in the other room. He would come back in the middle of the night, pull the cover away from me, slap my face, and then bear down on me with all his weight. I kept my eyes closed and abandoned my body. It lay there under him without movement, emptied of all desire, or pleasure, or even pain, feeling nothing. A dead body with no life in it at all, like a piece of wood, or an empty sock, or a shoe. Then one night his body seemed heavier than before, and his breath smelt different, so I opened my eyes. The face above me was not Bayoumi’s. `Who are you?’ I said. `Bayoumi,’ he answered. I insisted, ‘You are not Bayoumi. Who are you?’ `What difference does it make? Bayoumi and I are one.’ Then he asked, ‘Do you feel pleasure?’ `What did you say?’ I enquired. `Do you feel pleasure?’ he repeated. I was afraid to say I felt nothing so I closed my eyes once more and said, `Yes.’ He sank his teeth into the flesh of my shoulder and bit me several times in the breast, and then over my belly.”

Nawal el Saadawi (Kafr Tahla, 27 oktober 1931)

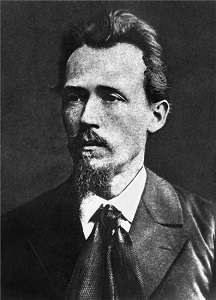

De Belgische dichter en schrijver Albrecht Rodenbach werd geboren te Roeselare op 27 oktober 1856. Zie ook alle tags voor Albrecht Rodenbach op dit blog.

Het klooster

‘k Kwam gewandeld gansch aleene.

De avond viel, de zonne zonk,

smeltend ginder ver in ’t westen,

langzaam weg in roeden gloed.

Váér mij’ lag het rustig kerkhof,

achter mij strekte de stee;

en ik ging voorbij het klooster,

langs de groene hagen heen,

tot ik stil bleef staan vóór ’t kerksken,

met zijn scherpe torennaald,

van de zone rood beschongen,

huis van vrede en heiligheid.

’t Kloksken viel opeens aan ’t luiden,

en ik trad het kerksken in.

’t Altaar stond van ’t licht te schitteren.

menschen knielden, hier en daar,

en de priester, de koralen,

traden op en ’t lof begon.

Nevens ’t altaar achter traliën,

schoof een groen gordijn nu weg,

en ik hoorde maagden zingen,

eerst gezamenlijk in koor,

dan opeens een enkle stemme,

wijl ’t Hoogweerdig, plechtig in

’s priesters handen, over ’t buigend

volk, het kruisgebaar volbracht.

’t Maagdenherte scheen te kloppen,

als zij zong « Adoro te.»

Lieve zusters, Jezus’ maagden,

ook mijn herte was ontroerd,

en ge zoudet ’t geerne schenken,

wist gij wat ik wenschte dan.

Een gebed voor mij, die jong ben,

een gebed voor dezen tijd,

die mij rollen zal en wentelen,

lijk de zee de bare rolt.

«Recht door zee» wil ik toch varen,

zusters, een gebed voor mij.

Albrecht Rodenbach (27 oktober 1856 – 23 juni 1880)

Zie voor nog meer swchrijvers van de 27e oktober ook mijn vorige blog van vandaag.