De Duitse schrijfster Gabriele Wohmann werd op 21 mei 1932 in Darmstadt geboren als Gabriele Guyot. Zie ook alle tags voor Gabriele Wohmann op dit blog.

Uit: Ein netter Kerl

„Ach, sagte Nanni, sie seufzte und rieb sich den kleinen Bauch, ach ich bin erledigt, du liebe Zeit. Wann kommt die große fette Qualle denn wieder, sag, Rita, wann denn? Sie warteten alle ab.

Er kommt von jetzt an oft, sagte Rita. Sie hielt den Kopf aufrecht.

Ich habe mich verlobt mit ihm.

Am Tisch bewegte sich keiner. Rita lachte versuchsweise und dann konnte sie es mit großer Anstrengung lauter als die anderen, und sie rief: Stellt euch das doch bloß mal vor: mit ihm verlobt! Ist das nicht zum Lachen!

Sie saßen gesittet und ernst und bewegten vorsichtig Messer und Gabeln.

He, Nanni, bist Du mir denn nicht dankbar, mit der Qualle hab ich mich verlobt, stell dir das doch mal vor!

Er ist ja ein netter Kerl, sagte der Vater. Also höflich ist er, das muß man ihm lassen.

Ich könnte mir denken, sagte die Mutter ernst, daß er menschlich angenehm ist, ich meine, als Hausgenosse oder so, als Familienmitglied.

Er hat keinen üblen Eindruck auf mich gemacht, sagte der Vater.

Rita sah sie alle behutsam dasitzen, sie sah gezämte Lippen. Die roten Flecken in den Gesichtern blieben noch eine Weile. Sie senkten die Köpfe und aßen den Nachtisch.”

Gabriele Wohmann (21 mei 1932 – 22 juni 2015)

Cover verhalenbundel

De Amerikaanse schrijfster en journaliste Amy Waldman werd geboren op 21 mei 1969 in Los Angeles. Zie ook alle tags voor Amy Waldman op dit blog.

Uit: The Submission

“It’s French, the wallpaper,” the mayor’s aide, his woman on the jury, piped up. “My point being,” Ariana went on, “that gardens aren’t our vernacu-lar. We have parks. Formal gardens aren’t our lineage.” “Experiences matter more than lineages,” Claire said. “No, lineages are experiences. We’re coded to have certain emotions in certain kinds of places.” “Graveyards,” Claire said, an old tenacity rising within her. “Why are they often the loveliest places in cities? There’s a poem—George Herbert—with the lines: ‘Who would have thought my shrivel’d heart / Could have recover’d greennesse?'” A college friend had written the scrap of poetry in a condolence card. “The Garden,” she continued, “will be a place where we—where the widows, their children, anyone—can stumble on joy. My husband . . .” she said, and everyone leaned in to listen. She changed her mind and stopped speaking, but the words hung in the air like a trail of smoke. Which Ariana blew away. “I’m sorry, but a memorial isn’t a grave-yard. It’s a national symbol, an historic signifier, a way to make sure anyone who visits—no matter how attenuated their link in time or ge-ography to the attack—understands how it felt, what it meant. The Void is visceral, angry, dark, raw, because there was no joy on that day. You can’t tell if that slab is rising or falling, which is honest—it speaks ex-actly to this moment in history. It’s created destruction, which robs the real destruction of its power, dialectically speaking. The Garden speaks to a longing we have for healing. It’s a very natural impulse, but maybe not our most sophisticated one.” “You have something against healing?” Claire asked. “We disagree on the best way to bring it about,” Ariana answered.

“I think you have to confront the pain, face it, even wallow in it, before you can move on.” “I’ll take that under consideration,” Claire retorted. Her hand clamped over her wineglass before the waiter could fill it.

Paul could barely track who was saying what. His jurors had devoured the comfort food he had requested—fried chicken, mashed potatoes, brussels sprouts with bacon—but the comfort was scant. He prided him-self on getting along with formidable women—was, after all, married to one—but Claire Burwell and Ariana Montagu together strained him, their opposing sureties clashing like electric fields, the room crackling with their animus. In her critique of the Garden’s beauty, of beauty itself, Pauk sensed Ariana implying something about Claire.”

Amy Waldman (Los Angeles, 21 mei 1969)

De Amerikaanse schrijfster en scenariste Maria Keogh Semple werd geboren op 21 mei 1964 in Santa Monica, Californië. Zie ook alle tags voor Maria Semple op dit blog.

Uit: This One Is Mine

“With enough Ivy League pluck to sit on a dirty sidewalk and not care who saw her? It was done and done. He had to have her. As he stepped forward, she absentmindedly twisted her long hair off her neck. That’s when he first glimpsed the tattoo behind her ear, teasing him from the edge of her hairline. He found it wildly sexy.

But something inside him sank. He knew then there’d be a part of her he’d never possess.

“I’ll get her, I’ll get her, I’ll get her.” Violet threw off the covers and trudged to Dot’s room without looking up. The violets. Those fucking violets.

David headed to the kitchen, comforted by the sounds of the morning: babbling Dot, the hiss of brewing coffee, the crunch of Rice Krispies underfoot. These days, there were two kinds of Rice Krispies, those waiting to be stepped on and those that already had been.

Pffft. He landed on some Krispy dust. “Dada!” Dot shouted. She sat with perfect posture at her miniature wooden table, covered head to toe in croissant flakes, a darling, crusty monster.

“Aww, good morning!” David said, stepping on some Krispy virgins. “That’s what I like to see, my girls!” A carafe of coffee and his newspaper awaited. “Honey,” he said to Violet, “there’s something floating in the Jacuzzi.”

Violet opened the fridge. “What?”

He walked to the window. “It looks like a dead gopher.”

“Then it’s probably a dead gopher.” She rooted around in the fridge. “Ah! There it is.” She tore white butcher paper from a hunk of cheese. At least she still did that for him, got him the good cheese.

“How long has it been there?” David asked.

“Mama, what’s dat?” said Dot.

“It’s cheese, sweetie.” Violet sliced some off.

“Want dat.”

“I’ll get you some. First, I’m making Dada his breakfast.”

“How long has the gopher been there?” David repeated.

“I don’t know. This is the first I’ve heard of it.” Violet placed David’s breakfast on the counter: wheat toast, sheep’ s- milk cheese, sliced apples sprinkled with lemon juice and freshly grated nutmeg”.

Maria Semple (Santa Monica, 21 mei 1964)

De Zwitserse schrijver Urs Widmer werd geboren op 21 mei 1938 in Basel. Zie ook alle tags voor Urs Widmer op dit blog.

Uit: TOP DOGS

„WRAGE Nein, nein. Die Damen und Herren haben alle der Leitungsebene angehört. “Top Dogs”. Ihre Preisklasse, wenn ich das mal so flapsig sagen darf. Unser Kerngeschäft bleibt die intensive Arbeit mit Klienten wie Ihnen. Deer versteht “wie ihnen”, das heißt wie mit denen da, nickt anteilnehmend. Wir führen sogar das Senior-Executive-Programm, das von Konzernchefs in Anspruch genommen wird. Stellenlos gewordene Persönlichkeiten der Führungsspitze.

DEER Musste ja selber Mitarbeiter entlassen. Als wir das Catering auslagerten, neunzehnzweiundneunzig, haben wir mehr als tausend Stellen abgebaut. Gute Leute, waren zum Teil seit Jahren dabei gewesen. Ist ein menschliches Problem, so was. Andererseits, im Kader, das ist einfach im Anforderungsprofil, so was wegstecken zu können.

WRAGE Ich muss sagen, Herr Deer. Chapeau! Aber eigentlich schüttelt es jeden. Pause. Entscheidend für unsre erfolgreiche Arbeit ist, dass diese immer und in jedem Fall vom ehemaligen Arbeitgeber finanziert wird. Dabei berechnen wir ganz bewusst eine Pauschale und nicht etwa ein Honorar, das sich nach der Vermittlungsdauer richtet. Denn so haben auch wir ein vitales Interesse daran, unsere Klienten schnell zu platzieren. Und optimal. Wir garantieren, sie ins Programm zurückzunehmen, wenn es mit dem neuen Arbeitgeber innerhalb eines Jahres zu Unstimmigkeiten kommen sollte.

DEER vertraulich Denen da geb ich keine Chance. Zu alt, zu unbeweglich, zu teuer.

WRAGE Sagen Sie das nicht. Wir hatten einen Herrn, Mitte fünfzig, der tauchte fünfmal wieder hier auf. Zuerst dachten wir, es liege an uns. Dann, dass es doch an ihm liegen könnte. Aber nein. Heute ist er Direktor eines führenden Touristikunternehmens und verbringt die meiste Zeit an sonnenüberfluteten Sandstränden. Heiterkeit.

DEER Ist bei mir nicht drin, Ferien. Bin ja ursprünglich Maschineningenieur. Workaholic. Dass ich bei der Swissair gelandet bin, an der Front zuerst, dann im Catering, hat sicher damit zu tun. Sechzehnstundentage. Wer beim Catering dabei sein will, muss Tag und Nacht am Ball sein. “Lead, follow or get out of the way”,nicht wahr. Lacht.”

Urs Widmer (21 mei 1938 – 2 april 2014)

Scene uit een opvoering in Hildesheim, 2003

De Vlaamse dichter Emile Verhaeren werd geboren in Sint Amands op 21 mei 1855. Zie ook alle tags voor Emile Verhaeren op dit blog.

Verstilde monniken

Er zijn verstilde monniken die zo zacht kijken

Dat in hun hand rozen en palmen moesten prijken,

Dat er een baldakijn, bleekblauw als ’t hemelblauw

Moest komen, dat men boven hun hoofd dragen zou,

En voor hun voeten die door ’s levens vlakte schrijden

Een zilveren pad dat naar een gouden weg zou leiden;

Door meren, langs rivieren volgden zij hun baan,

Alsof een witte stoet van lelies daar zou gaan.

Die monniken, die kaarslicht dragen in hun zinnen,

Blijven als kinderen de Heilige Maagd beminnen,

Zij staan in vuur en vlam en maken haar bekend

Als ster der zee en luister van het firmament,

Zij laten in de wind haar lofprijzingen horen

Met gulden lippen als van serafijnenkoren,

Zij wijden haar gebeden met zo’n vurigheid

En zo’n verzengend hart, dat zich hun oog verwijdt.

De dienst die zij haar wijden gaat hen zo ter harte

Dat hun geloof de vuren van de hel zou tarten

En dat zij ’s avonds in een liefdesvisioen

De vroomsten loont en hun haar Jezus schenkt als zoen.

Vertaald door Paul Claes

The Mill

Deep in the evening slowly turns the mill

Against a sky with melancholy pale;

It turns and turns, its muddy-coloured sail

Is infinitely heavy, tired, and ill.

Its arms, complaining arms, in the dawn’s pink

Rose, rose and fell; and in this o’ercast eve,

And deadend nature’s silence, still they heave

Themselves aloft, and weary till they sink.

Winter’s sick day lies on the fields to sleep;

The clouds are tired of sombre journeyings;

And past the wood that gathered shadow flings

The ruts towards a dead horizon creep.

Around a pale pond huts of beechwood built

Despondently squat near the rusty reeds;

A lamp of brass hung from the ceiling bleeds

Upon the wall and windows blots of gilt.

And in the vast plain, with their ragged eyes

Of windows patched, the suffering hovels watch

The worn-out mill the bleak horizon notch, –

The tired mill turning, turning till it dies.

Vertaald door Jethro Bithell

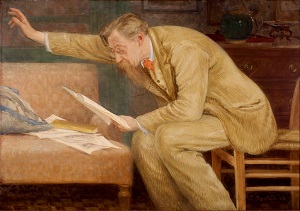

Emile Verhaeren (21 mei 1855 – 27 november 1916)

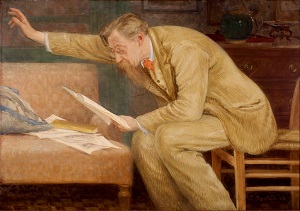

“La lecture”. Portret van Emile Verhaeren door Constant Montald, 1908

De Amerikaanse dichter Robert Creeley werd geboren op 21 mei 1926 in Arlington, Massachusetts. Zie ook alle tags voor Robert Creeley op dit blog.

Myself

What, younger, felt

was possible, now knows

is not – but still

not changed enough –

Walked by the sea,

unchanged in memory –

evening, as clouds

on the far-off rim

of water float,

pictures of time,

smoke, faintness –

still the dream.

I want, if older,

still to know

why, human, men

and women are

so torn, so lost,

why hopes cannot

find better world

than this.

Shelley is dead and gone,

who said,

‘Taught them not this –

to know themselves;

their might could not repress

the mutiny within,

And for the morn

of truth they feigned,

deep night

Caught them ere evening…’

America

America, you ode for reality!

Give back the people you took.

Let the sun shine again

on the four corners of the world

you thought of fast but do not

own, or keep like a convenience.

People are your own word, you

invented that locus and term.

Here, you said and say, is

where we are. Give back

what we are, these people you made.

us, and nowhere but you to be.

Robert Creeley (21 mei 1926 – 30 maart 2005)

De Engelse dichter Alexander Pope werd geboren in Londen op 21 mei 1688. Zie ook alle tags voor Alexander Pope op dit blog.

The Rape of the Lock: Canto 1 (Fragment)

Oft, when the world imagine women stray,

The Sylphs through mystic mazes guide their way,

Thro’ all the giddy circle they pursue,

And old impertinence expel by new.

What tender maid but must a victim fall

To one man’s treat, but for another’s ball?

When Florio speaks, what virgin could withstand,

If gentle Damon did not squeeze her hand?

With varying vanities, from ev’ry part,

They shift the moving toyshop of their heart;

Where wigs with wigs, with sword-knots sword-knots strive,

Beaux banish beaux, and coaches coaches drive.

This erring mortals levity may call,

Oh blind to truth! the Sylphs contrive it all.

Of these am I, who thy protection claim,

A watchful sprite, and Ariel is my name.

Late, as I rang’d the crystal wilds of air,

In the clear mirror of thy ruling star

I saw, alas! some dread event impend,

Ere to the main this morning sun descend,

But Heav’n reveals not what, or how, or where:

Warn’d by the Sylph, oh pious maid, beware!

This to disclose is all thy guardian can.

Beware of all, but most beware of man!”

He said; when Shock, who thought she slept too long,

Leap’d up, and wak’d his mistress with his tongue.

‘Twas then, Belinda, if report say true,

Thy eyes first open’d on a billet-doux;

Wounds, charms, and ardors were no sooner read,

But all the vision vanish’d from thy head.

And now, unveil’d, the toilet stands display’d,

Each silver vase in mystic order laid.

First, rob’d in white, the nymph intent adores

With head uncover’d, the cosmetic pow’rs.

A heav’nly image in the glass appears,

To that she bends, to that her eyes she rears;

Th’ inferior priestess, at her altar’s side,

Trembling, begins the sacred rites of pride.

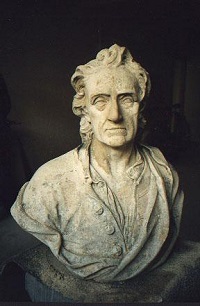

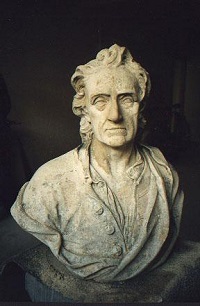

Alexander Pope (21 mei 1688 – 30 mei 1744)

Borstbeeld door Michael Rysbrack, midden 18e eeuw

De Roemeense dichter en schrijver Tudor Arghezi werd geboren op 21 mei 1880 in Boekarest. Zie ook alle tags voor Tudor Arghezi op dit blog.

Mount Of Olives

Mount with heaven-pointed peak,

Steady in blue dream.

Beaten by ancient hate

With chain whips

The flattened plain, hungry for height,

Watches its chance to rise above you,

Bring you the dust

Roused by flocks and clumps of men.

Mount, censers of springs,

Altar of hawks, house of suns,

Denying the brief flower

Drunk with its fragrance –

You at the margin of great mysteries

Are a sign of lasting power,

Irremedial life,

Most hemmed-in of stars!

Our soul, flimsy and poor,

Knows nothing of springs and harvests.

Our hope wanders among us,

Leaves its faint track in the mud,

A wheel with gold spokes.

Zwischen zwei Nächten

Ich habe die scharfe Schaufel in der Stube bei mir eingestochen.

Draußen schlug der Wind an. Draußen war Regen.

Und ich habe die Stube bei mir tief in die Erde aufgegraben.

Draußen schlug der Regen an. Draußen war Wind.

Ich habe die Erde aus der Grube durchs Fenster geworfen.

Die Erde war schwarz, sein Vorhang blau.

Vor den Scheiben ist die Erde aufgestiegen, bis oben hin.

Wie die Welt, so hoch war der Gipfel, und auf dem Gipfel weinte Jesus.

Beim Graben ist die Schaufel kaputtgegangen. Der sie schartig werden ließ, sieh an,

mit steinhartem Gebein war das doch der Vater selbst.

Und ich bin durch die Zeiten dahin zurückgekommen, wo ich hinabgestiegen war,

und in der leeren Stube habe ich mich wieder gegraust.

Und da habe ich hinaufsteigen wollen und auf dem Gipfel sein.

Ein Stern war in den Himmeln. Im Himmel war es spät.

Vertaald door Hartmut Köhler

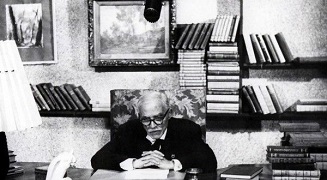

Tudor Arghezi (21 mei 1880 – 14 juli 1967)

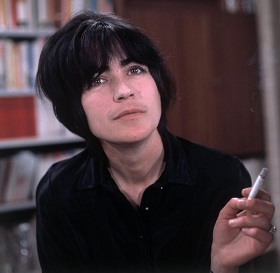

De Vlaamse schrijfster Suzanne Lilar werd geboren als Suzanne Verbist in Gent op 21 mei 1901. Zie ook alle tags voor Suzanne Lilar op dit blog.

Uit: Une enfance gantoise

« Parce que Maman était amoureuse de Gand presque autant que de mon père, elle me promenait tantôt à la cour du Prince et tantôt au Rabot. Ces hauts lieux empruntaient l’un et l’autre à la mythologie. Du premier où Charles Quint était né, conférant à notre cité sa dignité impériale, ne subsistait qu’un passage voûté qui me faisait rêver, car je m’efforçais d’accorder son exiguïté à la magnificence du palais disparu. Quant au second, qui avait conservé ses grosses tours se mirant dans la Liève et sa façade à redans, c’est aux fonctions pourtant modestes qu’y exerçait mon père qu’il devait son prestige. Cet ouvrage militaire du xve siècle avait en effet donné son nom à une gare qu’il surplombait de son architecture massive — gare qui n’était même pas gare de voyageurs et dont mon père était le chef. Maman n’avait pas eu de peine à m’enseigner l’honneur qu’il y avait à occuper ce poste. J’en sentais tout le poids lorsque j’étais admise à pénétrer dans le bureau de mon père, grisée d’avance de l’odeur poussiéreuse et administrative des liasses où jaunissaient probablement ses rapports. Mais rien ne me plaisait comme de le surprendre dans l’exercice de ses fonctions. Maman me l’accordait pour récompense. Je mettais ma main dans la sienne, toujours si doucement gantée. Nous prenions le chemin de la rue du Poivre et du béguinage Sainte-Elisabeth. Bientôt m’apparaissaient les tours du Rabot. Nous nous placions un peu à l’écart de façon à observer mon père sans en être vues. D ne tardait pas à se montrer. La tête crânement coiffée du képi de chef de gare, galonné d’or, il dirigeait, d’un ordre bref ou d’un coup de sifflet impératif, la répartition et le mouvement des convois. Je le regardais aller et venir, organiser une manoeuvre, ajouter ou déplacer une rame, donner le départ à une locomotive haletante et qui crachait de grands jets de vapeur. Je le trouvais grandiose. Je comprenais ma mère. Il était l’homme qui commandait au monstre. J’adhérais sans effort au culte familial.”

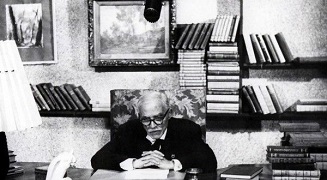

Suzanne Lilar (21 mei 1901 – 12 december 1992)

In de jaren 1960