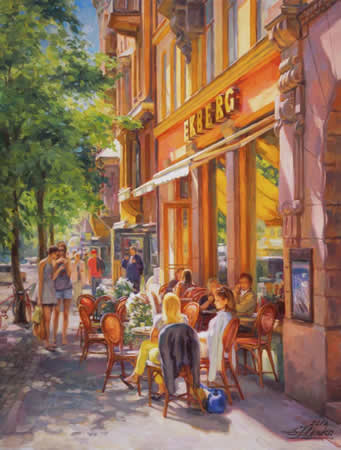

Dolce fa niente

Rain in Summer

How beautiful is the rain!

After the dust and heat,

In the broad and fiery street,

In the narrow lane,

How beautiful is the rain!

How it clatters along the roofs,

Like the tramp of hoofs

How it gushes and struggles out

From the throat of the overflowing spout!

Across the window-pane

It pours and pours;

And swift and wide,

With a muddy tide,

Like a river down the gutter roars

The rain, the welcome rain!

The sick man from his chamber looks

At the twisted brooks;

He can feel the cool

Breath of each little pool;

His fevered brain

Grows calm again,

And he breathes a blessing on the rain.

From the neighboring school

Come the boys,

With more than their wonted noise

And commotion;

And down the wet streets

Sail their mimic fleets,

Till the treacherous pool

Ingulfs them in its whirling

And turbulent ocean.

In the country, on every side,

Where far and wide,

Like a leopard’s tawny and spotted hide,

Stretches the plain,

To the dry grass and the drier grain

How welcome is the rain!

In the furrowed land

The toilsome and patient oxen stand;

Lifting the yoke encumbered head,

With their dilated nostrils spread,

They silently inhale

The clover-scented gale,

And the vapors that arise

From the well-watered and smoking soil.

For this rest in the furrow after toil

Their large and lustrous eyes

Seem to thank the Lord,

More than man’s spoken word.

Near at hand,

From under the sheltering trees,

The farmer sees

His pastures, and his fields of grain,

As they bend their tops

To the numberless beating drops

Of the incessant rain.

He counts it as no sin

That he sees therein

Only his own thrift and gain.

These, and far more than these,

The Poet sees!

He can behold

Aquarius old

Walking the fenceless fields of air;

And from each ample fold

Of the clouds about him rolled

Scattering everywhere

The showery rain,

As the farmer scatters his grain.

He can behold

Things manifold

That have not yet been wholly told,–

Have not been wholly sung nor said.

For his thought, that never stops,

Follows the water-drops

Down to the graves of the dead,

Down through chasms and gulfs profound,

To the dreary fountain-head

Of lakes and rivers under ground;

And sees them, when the rain is done,

On the bridge of colors seven

Climbing up once more to heaven,

Opposite the setting sun.

Thus the Seer,

With vision clear,

Sees forms appear and disappear,

In the perpetual round of strange,

Mysterious change

From birth to death, from death to birth,

From earth to heaven, from heaven to earth;

Till glimpses more sublime

Of things, unseen before,

Unto his wondering eyes reveal

The Universe, as an immeasurable wheel

Turning forevermore

In the rapid and rushing river of Time.

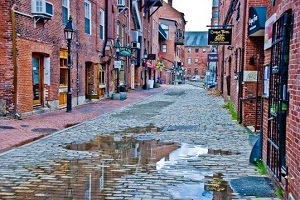

Portland, Maine. Wharf Street na de regen. Henry Longfellow werd geboren in Portland

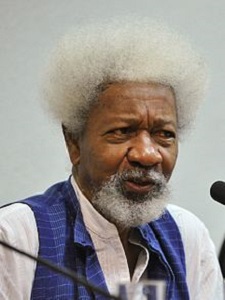

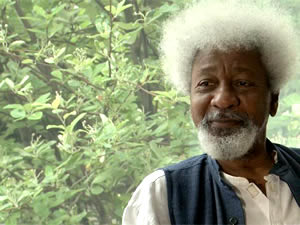

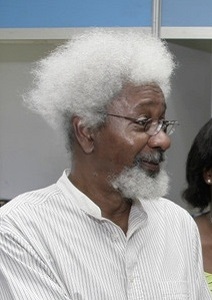

De Nigeriaanse dichter, schrijver en voorvechter van democratie Akinwande Oluwole “Wole” Soyinka werd geboren op 13 juli 1934 in Abeokuta. Zie ook alle tags voor Wole Soyinka op dit blog.

Uit: Aké. The Years of Childhood

“The

bedroom door opened and mother peeped in. Seeing me awake she entered,

and was followed in by father. When I asked for Osiki, she gave me a

peculiar look and turned to say something to father. I was not too sure,

but it sounded as if she wanted father to tell Osiki that killing me

was not going to guarantee him my share of iyan. I studied their faces

intently as they asked me how I felt, if I had a headache or a fever and

if I would like some tea. Neither would touch on the crucial question,

so finally I decided to put an end to my suspense. I asked them what

they had done with my dansiki.

‘It’s going to be washed,’ mother said, and began to crush a halftablet in a spoon for me to take.

‘What did you do with the blood?’

She

stopped, they looked at each other. Father frowned a little and reached

forward to place his hand on my forehead. I shook my head anxiously,

ignoring the throb of pain this provoked.

‘Have you washed it away?’ I persisted.

Again

they looked at each other. Mother seemed about to speak but fell silent

as my father raised his hand and sat on the bed, close to my head.

Keeping his eyes on me he drew out a long, ‘No-o-o-o-o.’

I

sank back in relief. ‘Because, you see, you mustn’t. It wouldn’t matter

if I had merely cut my hand or stubbed my toe or something like that –

not much blood comes out when that happens. But I saw this one, it was

too much. And it comes from my head. So you must squeeze it out and pump

it back into my head. That way I can go back to school at once.’

My father nodded agreement, smiling. ‘How did you know that was the right thing to do?’

I looked at him in some surprise, ‘But everybody knows.’

Then

he wagged his finger at me, ‘Ah-ha, but what you don’t know is that we

have already done it. It’s all back in there, while you were asleep. I

used Dipo’s feeding-bottle to pour it back.’

I was satisfied. ‘I’ll be ready for school tomorrow’ I announced.”

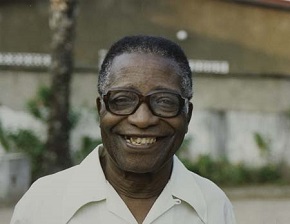

De Nederlandse dichter en (toneel)schrijver Rien Vroegindeweij werd geboren in Middelharnis op 13 juli 1944. Zie ook alle tags voor Rien Vroegindeweij op dit blog.

Onweer

Ik hou van de hete zon

die schittert op de rivier

en ik ben gek op de eerste

kou van de winter. Ik hou

van de zon die ondergaat

en zou, als ik de kans kreeg,

ook genieten van een kort

doch hevig bosbrandje. Ik hou

van mijn moeder die oud is

en na een godvruchtig leven

niet weet wat het worden zal,

de hel of de hemel. Ik lijk

op haar omdat mijn dochter

op haar lijkt. Maar ik maak

haar niet bang met het vuur

dat opstijgt rond de zondaars.

Noch vrolijk ik haar op

met het vooruitzicht op hemels

gezang: als zij mijn hand vast

houdt, durf ik voor het raam

te staan, als zij lacht om mijn

oud geloof dat God in de donder

spreekt, praat zij hem na

en zegt: boemdereboemboemboem.

Dierbaar

Niet de aap maar het paard

lijkt het meest op de mens,

als je ’t in de ogen kijkt.

Of sla de boeken erop na,

veldslagen, ontdekkingsreizen,

de melkboer in de straat.

Held van ’t wilde Westen,

ruilobject voor koninkrijken,

verlosser van de filosoof.

Hier en daar staat op een plein

in brons een krijgsheer op zijn paard,

– dat zou andersom moeten zijn.

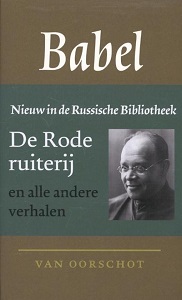

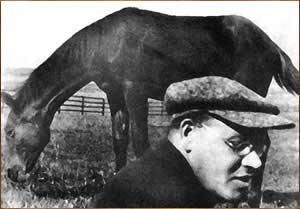

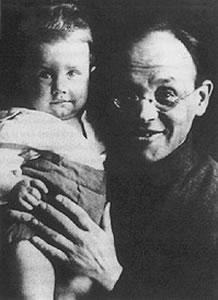

De Russische schrijver Isaak Emmanuïlovitsj Babel werd geboren in Odessa op 13 juli 1894. Zie ook alle tags voor Isaak Babel op dit blog.

Uit: De geschiedenis van mijn duiventil (Vertaald door Froukje Slofstra)

“In

onze winkel zat een klant, een boer, zich besluiteloos het hoofd te

krabben. Toen hij mij zag, liet mijn vader de boer achter en hij hoorde

gretig, zonder enige scepsis, mijn verhaal aan. Hij riep de bediende om

de winkel te sluiten en snelde naar de Sobornaja-straat om een pet met

het schoolembleem voor mij te kopen. Mijn arme moeder kon me nauwelijks

van die uitzinnige man wegrukken. Mijn moeder zag bleek op dat moment en

peilde het lot. Ze aaide over mijn hoofd en duwde me dan weer vol

weerzin weg. Ze zei dat de krant de namen publiceerde van de jongens die

waren toegelaten tot het gymnasium en dat God ons zou straffen en de

mensen ons zouden uitlachen als we voortijdig een schooluniform kochten.

Mijn moeder zag bleek, ze peilde het lot in mijn ogen en keek naar me

met bitter medelijden, als naar een kreupele, omdat alleen zij wist hoe

ongelukkig onze familie was.

Alle mannen van ons geslacht waren te

goed van vertrouwen en geneigd tot ondoordachte daden, we hadden nergens

geluk in gehad. Mijn grootvader was ooit rabbijn geweest in Belaja

Tserkov, hij was wegens godslastering verjaagd en had nog veertig jaar

tumultueus en armoedig verder geleefd, vreemde talen gestudeerd, en

vanaf zijn tachtigste zijn verstand verloren. Mijn oom Lev, de broer van

mijn vader, had aan de jesjiva in Volozjin gestudeerd, was in 1892

weggelopen uit de militaire dienst en had de dochter ontvoerd van een

intendant die in het militaire district Kiev diende. Oom Lev had die

vrouw meegenomen naar Californië, naar Los Angeles, had haar daar in de

steek gelaten en was gestorven in een dubieus huis, tussen negers en

Maleiers. Na zijn dood stuurde de Amerikaanse politie ons zijn erfenis

uit Los Angeles: een grote hutkoffer, beslagen met bruine ijzeren

banden. In die koffer zaten halters, lokken vrouwenhaar, mijn

grootvaders talliet, zweepjes met vergulde handgrepen en bloementhee in

met goedkope parels versierde kistjes. Van de hele familie waren alleen

mijn krankzinnige oom Simon, die in Odessa woonde, mijn vader en ik

over. Maar mijn vader was te goed van vertrouwen, hij beledigde de

mensen met zijn uitgelaten, idolate onthaal, dat vergaven ze hem niet en

ze bedrogen hem. Mijn vader geloofde derhalve dat zijn leven werd

geregeerd door een kwade genius, een ondoorgrondelijk wezen dat hem

achtervolgde en in niets op hem leek. En dus was ik voor mijn moeder de

enige die overbleef van onze hele familie.”

De Potjomkintrappen in Odessa

De Canadese schrijver Scott Symons werd geboren op 13 juli 1933 in Toronto. Zie ook alle tags voor Scott Symons op dit blog.

Uit: Place d’Armes

“To rest a moment … slowly it focused him … drew him out again — he heard the thunder of the candles … and again his eardrums were probed and penetrant — again he lost his male maidenhead … he reeled, held tight, and then relented … gave himself to the verity … and as he did he felt his eyes palped by the entrelacings of the gilt pillars .. and he followed the line of gold, up to the gold florescence under the balcony — to the scallopings of wood frieze … and he knew that he had to abandon himself to this … had to give to this — give himself to this. There was no other viable alternative. No other way — not out — but in. No other truth. Everything else was shadow. … for a moment the veil dropped again — threatened to drop — he tried to make his eye bounce back off the entrelacs … briefly he succeeded — yet he knew that if the veil did drop, he was lost — that once again he was still-born…. He looked back at the writhings of the gold … and as his eye turned to them, they shot in, under his guard, before he even knew what had happened … shot into him, writhing and convulsing — the candles raged in him — again he tried to close down — to shut out this realization … but now it was too late, gloriously, with absolute finality, too late … his whole body soared from the pew — followed his eyeballs in with the entrelacings … the roof lifted and he was adrift absolutely, afloat … no longer was there any question of details, of itemization — all that had gone now … he was confounded in utter conjugation with the body of the Church — it was militant in him. He turned — and staggered out … the Place d’Armes was outrageously alive in him … detonating everywhere, everything, in a profusion of knowledge … suddenly every detail was searingly evident — each outline blared in him, and the mass of the square raged in him … he saw the beaver again … and as he did heard the thunder of the candles … his throat swole, his eyes blazed … ca creve les yeux, Pierre had said — he was right — it stabbed your eyes out … no in … stabbed his eyes back in…. He was haemorrhaging now … could feel the stream of blood blurting from him … hideously alive…. La Place….The Place … he could see the Place … he started to shout … “La Place … it’s there … don’t you see … La Place … Look….” And he started to run toward the statue of Maisonneuve … and his run became a dance, his whole body vibrant, like the dancers in the nightclub, like the old High Altar by Quevillon in the Church, that was (he knew it now) the same altar as in his dream at home, as sideboard of hospitality, like the commode in the Flesh Market, like the sternum of the Lesser Sphinx … out into La Place, grasping Holy Host to place it in the very centre of La Place.”

Toronto

De Duitse schrijfster Rebecca Salentin werd geboren op 13 juli 1979 in Eschweiler. Zie ook alle tags voor Rebecca Salentin op dit blog.

Uit: Hintergrundwissen eines Klavierstimmers

„Die Übelkeit müsse wohl eine Form der Vorahnung gewesen sein. Denn noch nie war das Gewissen so hinterrücks über den Klavierstimmer hergefallen wie an jenem Tag. Jahrelang hatte Kazimierz das Gefühl der Scham mit sich herumgetragen, ohne zu wissen, wofür er sich schämte. In den letzten Tagen hatte er sich eingestanden, dass es die Mitwisserschaft war, die ihm ein Dauergefühl der Scham verursachte, dass ihm davon übel wurde. Dazu war eine Macke, ein Tick gekommen, den er sich selbst nie hatte erklären können: Wo immer er auch ging oder stand, was immer er auch tat, ständig sah der Klavierstimmer sich fallen, ausrutschen, stürzen und seinen Kopf auf Kanten knallen. Er sah sich, wie er sich den Schädel an Klavieren und Flügeln stieß, er sah sich auf Bordsteinkanten stürzen, wo sein Kopf blutig aufschlug. Er sah sich auf Treppen ausrutschen, den Hinterkopf hart auf den Stufen aufprallen, er sah sich gegen die Straßenbahnwagen laufen, deren Elektrizität ihm immer noch Angst einjagte, obwohl sie schon seit einigen Jahren die pferdebetriebene ersetzte, und sah seinen Kopf von der Härte des Aufpralls aus Nacken und Genick reißen. Fuhr er doch einmal mit der Straßenbahn, klammerte er sich mit schwitzigen Handflächen an die Metallstangen, dass es in den Kurven nur so quietschte, damit er nicht bei jeder Station den Halt verlöre und mit dem Kopf gegen Holzbänke, heruntergeklappte Fenster oder andere Passagiere stoße. Tischkanten musste er umklammern, um vor einer Kollision mit ihnen gefeit zu sein. Wenn er abends zu Bett lag und die Termine des nächsten Tages ordnete oder Vergangenes Revue passieren ließ, so sah er sich jedes Mal in dem Moment, in dem er das Wort ergriff, um seine eigene Meinung kundzutun, keine streitende oder rechthaberische, nein, nur seine ganz persönliche Meinung, in dem Moment, wo die Worte aus seinem Mund kamen und die Gesichter sich ihm zuwandten, sah er sich stürzen. Es reichte schon der Gedanke daran, Lieba oder Dawid um ein Brot zu bitten, und er sah seinen Kiefer auf ihre Verkaufstheke krachen, dass seine restlichen Zähne zersplitterten. Nie war eine dieser schmerzvollen Visionen Wirklichkeit geworden, er kannte andere seines Alters, die wirklich stürzten und fielen, er hatte sich jedoch, aus Angst vor dem Sturz, einen langsamen tastenden Gang angewöhnt. Er war immer sehr aufmerksam, besah jeden Schritt seiner Wege genau, schätzte alle Gefahren im Umkreis von einigen Metern mit den Augen ab, bevor er sich ein Gefühl der Entspannung zugestand. An diesem Nachmittag, in Karols Stube, hatte er sich gefragt, ob es die Ereignisse im dwór, zwanzig Jahre zuvor, gewesen waren, die ihm derart den Boden unter den Füßen wegzogen.“

Cover

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 13e juli ook mijn blog van 13 juli 2018 en ook mijn blog van 13 juli 2016 en ook mijn blog van 13 juli 2014 deel 2 en ook deel 3.